Introducing Arts & the City

The upcoming issue of BE is dedicated to “Arts and the City”. An all-encompassing remit if ever there was one, forcing editorial decisions at once about what we are and aren’t aiming to cover. Some indication of the depth of the waters in which we are fishing is perhaps given by the fact that Peter Hall’s “Cities in Civilization” devotes some 400 pages to ‘The City as Cultural Crucible’ (Book One, on the Renaissance, painting, theatre and so forth) and to ‘The Marriage of Art and Technology’ (Book Three, on Hollywood, the Delta blues and mass culture) out of its over a thousand pages: yes, Zweig, Stefan concludes the Index, on p.1169.

So many temptations: the fascination of places entwined in the history of art, from 15th century Florence, to Montmartre and Montparnasse a century ago, to Manhattan’s SoHo in the 1980s… Or the cities where the question of what makes a locus of innovation or creativity, how it’s sustained, why it might ebb...Or the vital role, in so many places, of arts and culture in providing key themes for tourism and visitor interest.

Figure 1: Powerful original Public Art: Budapest’s Holocaust memorial

So what did we decide to cover? Well, of course, the artists themselves: in the specific milieu of London’s East End, Nick Green’s “The Holding Option” looks at where the artists are today and where they were over the last half-century; why they chose that part of the city and what their presence meant, and means today. The article looks, too, at what their presence seems to do to the localities they chose: carefully unpicking the too-easily-made link between their arrival and citywide processes like gentrification; and showing what a dynamic story it’s been, of colonisation, displacement and movement.

That is to focus on the making of art. But our interest is also on cities’ roles in selling art, showing it, enjoying it and exploiting it. We’re interested in the places themselves, and what they’re doing about art and culture. Sometimes this is about ‘Art Districts’, and this can quite often mean something very different from a Shoreditch or a Hackney Wick. The ‘art district’ in a trading city like Dubai means that actual artists are hardly the dominant actors encountered when you walk around the ‘Al-Serkal Avenue’ area: a kind of instant ‘rundown-warehousing-art-district’ which is the subject of Damien Nouvel’s deep dive into its evolution: “Organic, Planned, or Both?” The Middle East provides, too, the canvas for Yasser El-Sheshtawy’s survey of the plethora of prestige cultural investments (think Louvre Abu Dhabi) which, as he says, is “Beyond Art-washing”: yes, it’s the industrial-strength variety of ‘art as city strategy’, but it does also relate to a wish to hold on to one’s own heritage, as Hollywood and Cairo drown the region in imported culture. Beyond the beyond, our visit to South Korea turns the art/ government /city nexus right around: Soyoon Choo & Elizabeth Currid-Halkett (“Socially Engaged Art(ists) and the 'Just Turn' in City Space”) relate and analyse the fascinating history of the Candlelight Plaza, where artists took over a main square in Seoul to frame questions about policy for the city and the arts in a way that ordinary residents could engage with.

Figure 2: ‘Prestige cultural investments’: Louvre Abu Dhabi as the epitome of a worldwide trend

What we do give a lot of attention to is government activity - at both national and local levels - aimed at encouraging, and benefitting from, art and art-related activity of many kinds. Obviously this also involves looking at how arts and the city interact with each other: what happens, and how it happens, as well as the policy-oriented questions about what they’re all trying to make happen.

This is quite a long history now, and Charles Landry’s overview of Arts, Culture & The City looks at the three decades or more during which cities worldwide have increasingly linked the arts, culture and creativity to urban revitalization: an effort he himself has been closely involved in developing and steering through his Comedia consultancy. One of the most ambitious and co-ordinated government initiatives has been running in the USA for the last ten years or so: focussing on the Creative Placemaking agenda and a cluster of actions to make places more of a creative milieu. Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa Nicodemus were closely engaged in this from the outset, and in “Arts & The City: Policy and its Implementation”, they show how such a government policy could be driven federally but implemented locally in many imaginative ways.

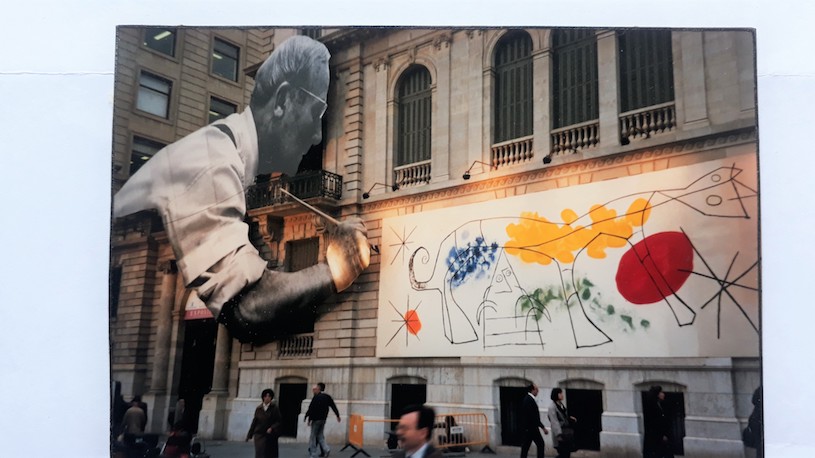

Figure 3: Miro brings Art to the City: Barcelona 1989

And whatever we do in this vein, let’s do it well. We were keen to also explore how to back policy with experience and skilled implementation, and this is the theme carried through by Vivien Lovell of Modus Operandi in her “Artists & the Public Spaces of the City”. She provides a practical guide to making Public Art programmes coherent, sustainable and attractive, and avoiding the well-meaning but random and irrelevant investments that are such a common feature in this sphere. Similarly practical is the guidance from a leading practitioner - Sherry Dobbin, of Future City and formerly the Times Square Alliance - interviewed by Anna Marazuela Kim in Can We Design for Culture?

Inevitably many other art forms don’t feature in our Arts & the City issue. No literary cities like Dublin or Trieste or Hay-on-Wye; no theatre cities (Edinburgh), or opera cities (Bayreuth, Verona). But we DO include the art and places of music: both rough-but-famous Liverpool (Ian Wray’s “The Pool of Life”) and staid-but-surprising Den Haag (“There's Music to Play, Places to Go, People to See!” from Amanda Brandellero and Robert Kloosterman).

“The act of creating art, whether a guitar riff, a concerto, a painting or a play, is a personal and unprogrammed thing. Nonetheless, cities can help create the conditions for that creation to happen, and for arts and culture to thrive.” So says the Editorial. Our contributors show many ways in which policy can nurture creative places. But it’s important to remember that the policies need a base of real creativity and, dare I say, technical competence: you can have all the right policies, committed local leaders and imaginative marketing of your cultural assets. But it might just turn out that, as the Liverpool case suggests, things like grassroots musical education, and a support network for and of musicians, are as likely to be the crucial elements for that art-form: a conclusion that echoes, mutatis mutandis, across many other sectors too.

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

Figure 1 (& listing image): Powerful original Public Art: Budapest’s Holocaust memorial (Source: © Martin Crookston, all rights reserved)

Figure 2: ‘Prestige cultural investments’: Louvre Abu Dhabi as the epitome of a worldwide trend (Source: NChavance via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Figure 3: Miro brings Art to the City: Barcelona 1989 (Source: © Martin Crookston, all rights reserved)