Digital planning for real smart cities

Jorge Gil, Guest Editor of the latest issue of Built Environment Vol 46.4 on City Information Modelling (or CIM), reflects on lessons for CIM from the current pandemic and beyond.

****

As I write these words, we are in the midst of a global health crisis that over the past few months forced us on a crash course in digitalisation of our everyday practices. Our diaries are packed with on-line meetings, workshops, and lectures, as our professional and social activities continue while respecting the need for physical distancing. We have become more used to collaborating on shared documents and discovered digital whiteboards. And we have been able to attend on-line seminars and conferences that would have otherwise been missed.

Everyone has also come to appreciate the critical value of information, based on scientific evidence and data, to support decisions in all spheres of life: health, education, economy, social and family relations, or travel. This data, available openly and updated daily, with global coverage, has been providing an up-to-date picture of the pandemic via the many charts, statistics, maps and models presented to the public.

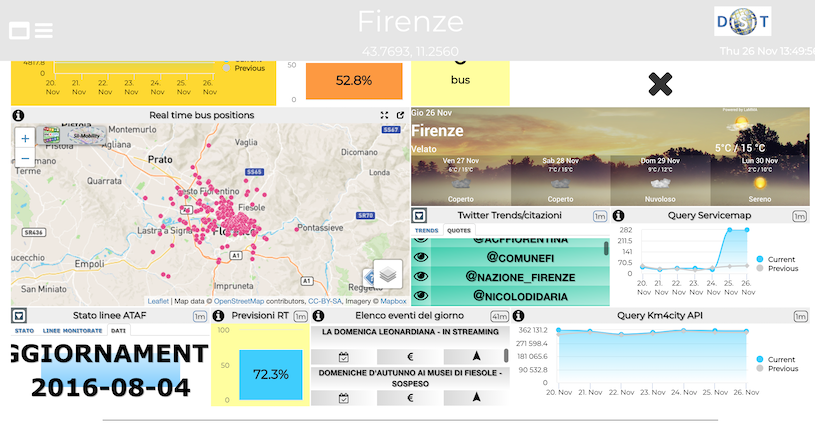

Figure 1. City dashboard of Florence.

The task of planning and designing our cities is no less of a challenge. Both in terms of the complexity of, and dynamic interaction between, the various stakeholders and various systems that make up the urban world, and in terms of the sustainability goals that we have set out to (urgently) meet in the coming decades, spelled out in the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the UN Habitat's New Urban Agenda. In this challenge, we must also look for support from data and scientific evidence, engaging in the science of cities towards the development of Smart Cities. We must collect, analyse, and visualise information on the physical, ecological, material resources, social, transportation and other urban systems, and make informed decisions as citizens and professionals. This path involves the increased digitalisation of urban design and planning processes, as a necessary transformation for supporting informed, transparent, collaborative, decision making and design. And City Information Modelling (CIM) is an emerging concept to frame such practice.

While technological and scientific innovation are fundamental to enabling the digital transformation towards the Smart City, we must not forget that this can only be realised if we have Smart Citizens and Smart Planners and Designers. As Cedric Price famously stated in 1966 "Technology is the answer, but what was the question?". A question that comes to mind, when we see the latest Smart City solutions and announcements of new Digital Twins, is: What about the people?

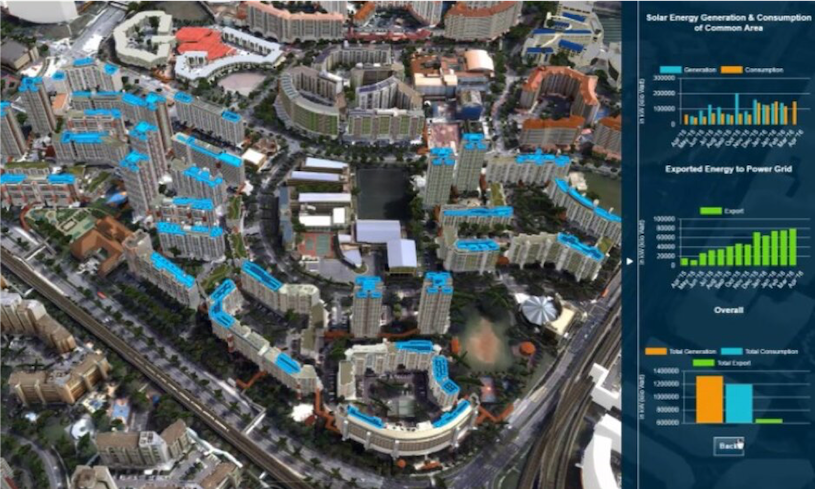

Streams of big data are being collected everywhere but it is unclear who has the capacity to process and make sense of all that data, other than machine learning algorithms, and transform it into meaningful and impactful planning decisions. Sophisticated dashboards and apps are produced to interface with such data streams, offering captivating visuals, but it is unclear if citizens and practitioners are actually using these tools. And the interactive 3D models of Digital Twins of cities, increasingly realistic and information rich, usually present a static snapshot of a city's building stock without the dynamic layers that are the essence of a living city: movement of people, goods and services, economic activities, social interactions, and the voices of its citizens. It is precisely the essence of the city that is not addressed by centring the debate around technologies, such as BIM and GIS, that inherently lack a conception of what a city is.

Figure 2. Virtual Singapore Digital Twin showing analysis of solar energy production potential.

For the digital transition of urban design and planning practice to be successful, we must start addressing people challenges. It does not make sense to develop tools that have no use or adoption, or standards that have no tools or data implementing them, nor models with unrealistic data demands. It is unlikely that we find a single vendor's software platform delivering all the necessary functionality for different users. It is important to engage with the various actors and stakeholders involved in planning and designing the city to support their processes. And it is important to enrich these processes with information, at multiple spatial and temporal scales, reflecting the many urban systems and stakeholders to ensure that these actors’ decisions are effective.

Figure 3. Digital urban design and planning tools supporting collaboration and participation.

We all hope to return to our normal lives as soon as possible, after overcoming this pandemic. Still, the digital transformation of our professional practices is here to stay, and it has even accelerated. Going forward, City Information Modelling should represent a digital urban design and planning practice by people, for people, with digital technologies at its core, and the sustainable and just smart city as its goal.

Read the issue on CIM, accessible from Ingenta at this link: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/alex/benv/2020/00000046/00000004

Images

Figure 1. City dashboard of Florence. (Source: https://dashboard.km4city.org/view/?iddasboard=MzA=&nome_dashboard=Firenze2)

Figure 2. Virtual Singapore Digital Twin showing analysis of solar energy production potential. (Source: https://www.nrf.gov.sg/programmes/virtual-singapore)

Listing Image/Figure 3. Digital urban design and planning tools supporting collaboration and participation. (Source: Photo by Marvin Meyer on Unsplash)

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!