Finding Value in the Public Space of Hong Kong

Dr Hee Sun Choi is a adjunct assistant professor at the Polytechnic University of Hong Kong, and co-director of CHOI-COMER ASIA in Hong Kong Inspired by issues 43.2 'public space & urban justice' & 44.1 'inclusive design' of the Built Environment journal, she presents a pictorial study of the value of urban public space. Looking at the configuration of four unique and distinctive public spaces in Hong Kong, she considers the possibilities of alternative designs.

‘City-ness’ has been defined as a simultaneous gathering and dispersing of evolving culture, information, and people (Shields, 2004). It is within the public open spaces of the city that this is perhaps most clearly reflected, and needed as a place to relax, play, gather and find joy. The densely populated and built up nature of the city of Hong Kong has been cited as a factor in the city’s low ranking at only 76th in the United Nations’ annual world happiness ranking (2018). With half of the city’s households living in spaces smaller than 500 square feet, it is important for Hong Kong to provide the public space to compensate. Whilst there is public space provision in the city it is in a relatively small quantity; a study by think tank Civic Exchange in 2018 found that the average open space available for each Hongkonger was about two square metres, which does not compare favourably with many other cities in Asia, including Shanghai, Singapore, Tokyo, and Seoul, whose residents enjoy a larger amount, within a range of 5.8 square meters to 7.6 square metres.

A further issue for Hong Kongers and their public space is that for some reason they tend not to make good use of it; a study by Zheng (2018) indicated that apart from the occasional peak periods public spaces for the most part remain fairly empty, with the on average recreational usage of public space for residents limited to 1-2 times a month. During the summer months the hot and humid weather is a factor that keeps people indoors, but these studies defined a greater driver for the lack of activity is that most users seldom think to visit or use the public spaces that surround them. How can the public spaces of Hong Kong be made more appealing and accessible?

To consider the urban context of this more broadly, the city and culture of Hong Kong is at a febrile and fascinating tipping point, with opposing factors influencing its social and spatial development. As Hong Kong approaches the midway point between in its fifty year transition from being a UK colony member to coming under the rule of China, the international context and trend towards homogenization represents an additional challenge to the cultural identity of this centre of global finance. In these circumstances, there has been a focus by certain academics on ideas of locality and place (McDowell, 1997; Jacob and Fincher, 1998; Lewis, 2002; Adam, 2010) and theoretical speculation about how these identities can inform the nature of the city’s public realm.

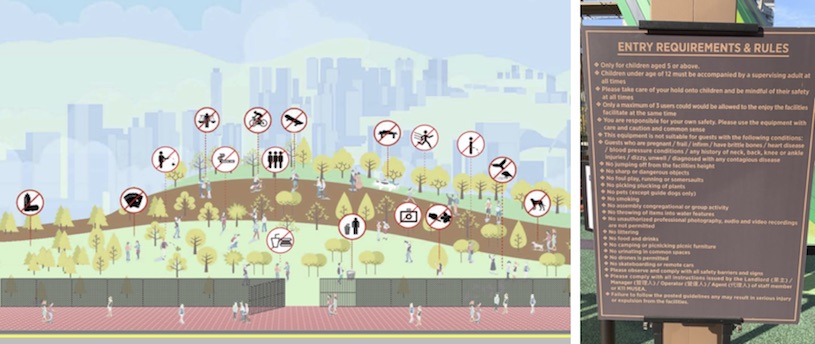

Inspired by all this, it is important to consider the limited physical condition, management levels of governments and private developers’ restricting the usage of the spaces they are responsible for, and overly rigid designs for public spaces and street furniture. All these factors limit either directly or indirectly how users can enjoy and express themselves within the urban open spaces of Hong Kong. In addition, in some public spaces there are barriers large and small restricting access and use; fencing, flat benches with obstructions and slanted benches designed in a hostile manner to prevent people from feeling truly comfortable. Alongside the physical constructions there are multiple restrictions in the usage of public space, to a greater degree than you would see in most other world cities.

Figure 1: Public space regulation and management

An important feature of public space is its ability to allow citizens to enjoy public life (Gehl,1996) and ensure that individuals are not isolated from the mass public. But what are the key factors that can increase the usage and enhance the experience of public space?

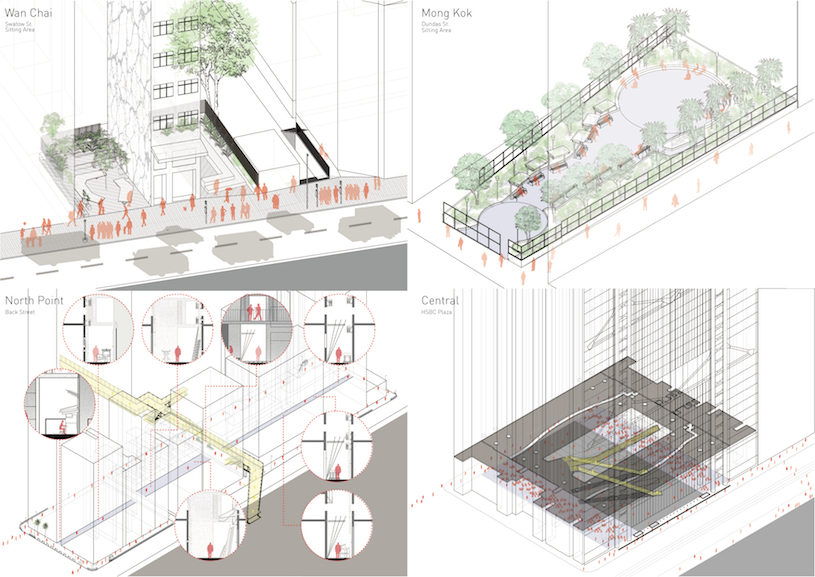

The following four public spaces in Hong Kong will be studied in this article; a particular form of public realm in Northpoint, a pocket park and sitting-out area in Wan Chai, a public garden in Mong Kok, and lastly a publicly accessible plaza within the HSBC, in Central.

Figure 2: Four study areas

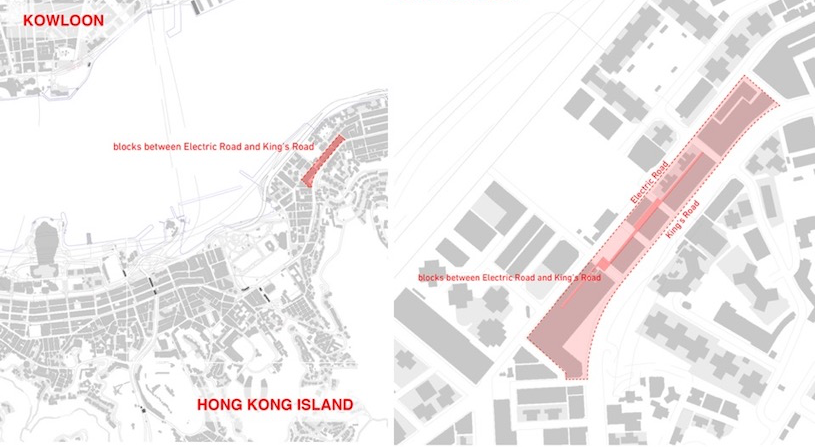

1. Java Road in North Point

Type: Backstreet

Management: Leisure and Cultural Services Department

North Point is a vibrant urban district in the eastern part of Hong Kong Island, populated with a good balance of places to live and work, across a fairly dense street pattern of busy through routes and more intimate lanes and backstreets. There is currently a large amount of development ongoing in this area, alongside existing building forms and typology.

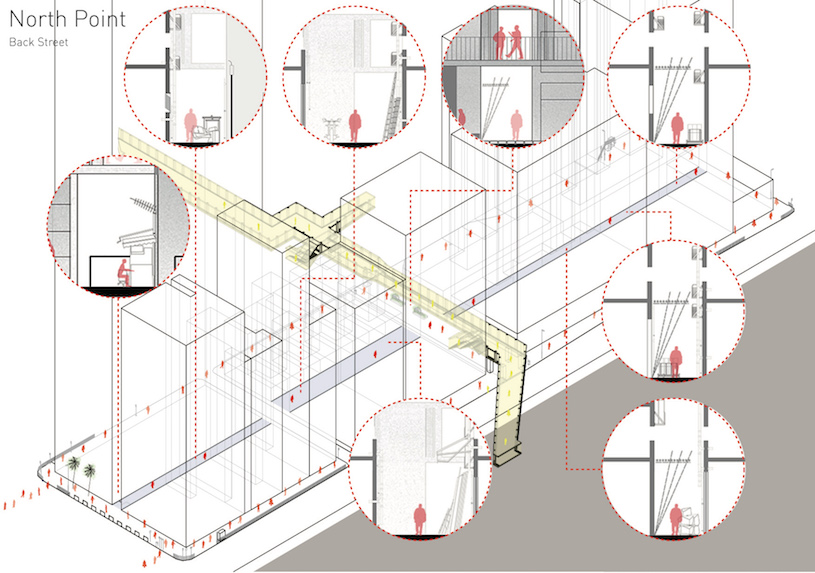

Figure 3: The backstreets of North Point

Java Road serves a mixed group of old and new buildings from the 60s to the 80s, with a human scale to the street and pavement, large apartment towers and low-rise shop-housing with residential apartments above (with balconies) and retail on the ground level. A noticeable consequence of the amalgamation of smaller building plots into larger blocks and development projects is how the finer grain and permeability of the existing streetscape is starting to disappear. The new development projects along Java Road tend to erect walls in an attempt to screen off the surrounding locale, rather than engage with it. The emphasis is on connection via elevated walkways to the nearest MTR train station, as a rejection of the street. This is a shame, because as a piece of urban design there is great interest and attraction in the permeability and varied usage from block to block and street to street. Although there is intriguing potential, the existing backstreets are currently either underused or poorly used, and risk being wiped out completely by new development, before there is the chance to consider how they could develop as an exciting and particular part of Hong Kong.

Figure 4: Animated sectional view showing the character of the backstreet adjacent to Java Road

2. Sitting-out areas on Swatow Street in Wan Chai

Type: Pocket Park

Management: Leisure and Cultural Services Department

These two very small pocket parks are located in Swatow street, in Wan Chai within a highly dense commercial area. Each park is approximately 32m2, and sit either side of a small building, alongside access lanes to the block behind, and facing a busy road and adjacent to a bus stop.

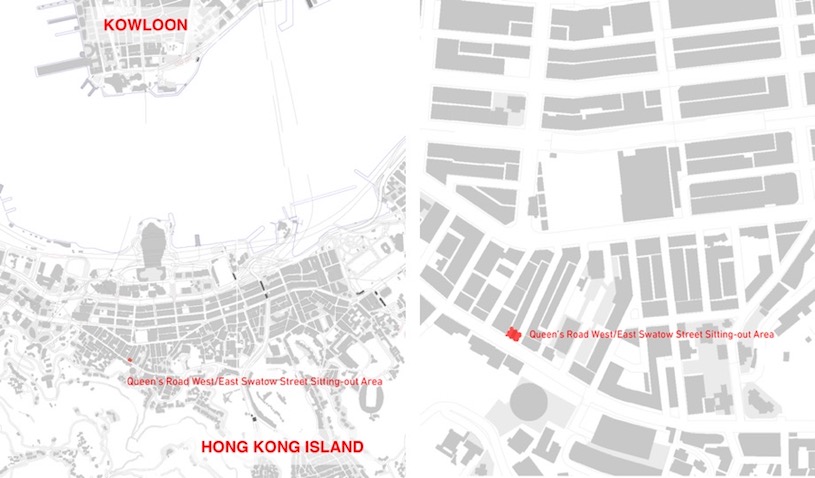

Figure 5: Swatow Street location plan

Although there were two phases of development to redesign this pocket parks since 2015, these pocket parks still include only a small amount of greenery. The renovated bench and planter arrangement, although still quite rigid, are expansive and open enough to providing users some flexibility in their activities.

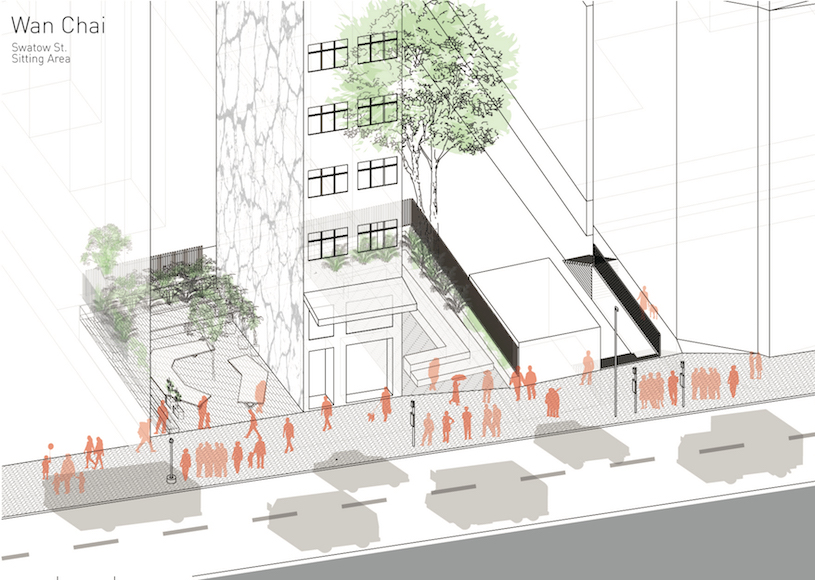

Figure 6: Swatow Street sitting out area, after two phases of renovation

There are no street lights, and painted concrete boundary walls without windows or balconies. Although the newly designed landscape in the pocket park is a more contemporary, open design to the one before it, there is a further opportunity to consider how smaller park space can offer an intimacy and enclosure’ a clear and identifiable place where people can relax and take refuge from the busy surroundings.

Figure 7: Swatow Street sitting out area, before and after renovation

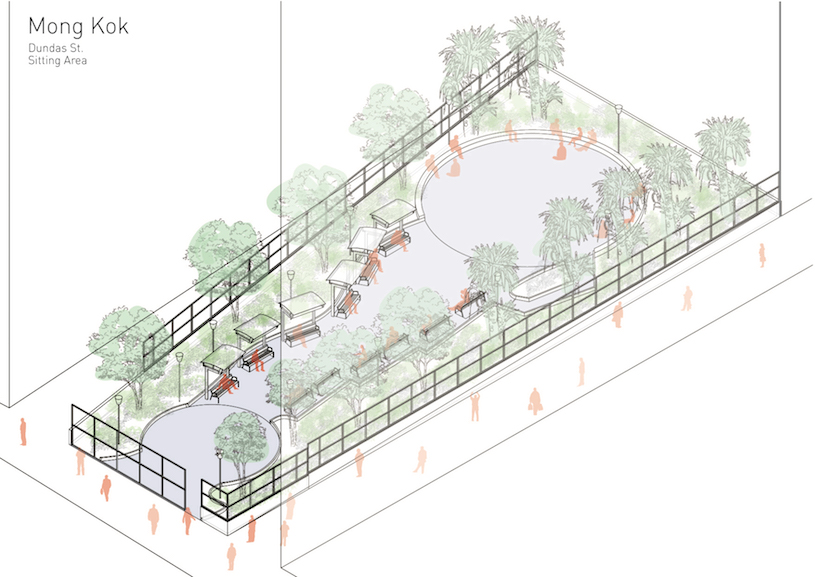

3 Mong Kok public garden, Kowloon

Type: Garden and Sitting-out Area

Management: Leisure and Cultural Services Department

Public space can be read as an expression of human endeavour and an artefact of the social world and the physical and metaphysical heart of the city. Considered in this way, public spaces should provide channels for movement, nodes of communication and common ground for cultural activities (Whyte, 1980). Public space extends our living area and is open to everyone in society, encouraging social interaction and bonding within the community.

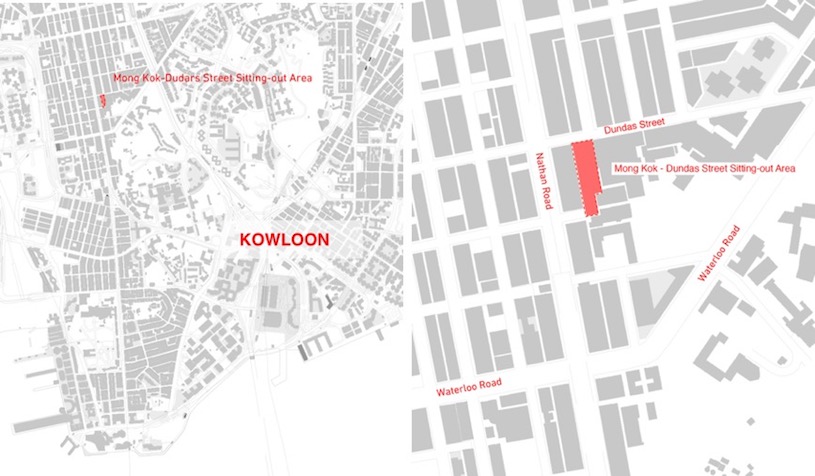

Figure 8: Public garden, Dundas Street Mongkok, location plan

This public garden and ‘open’ space in Mong Kok seems to miss the point, enclosed and separated as it is from the street life around it with a fortified fence of steel and concrete. The lawn, public furniture, trees, and lighting within the enclosure are of a resonable quality, but the enclosure and a few steps of elevation above the street make the place more inaccessible and isolated. This heavy handed approach to design, enclosure, access and control is unfortunately fairly common within Hong Kong’s small public spaces and pocket parks.

Figure 9: Public garden, Dundas Street Mongkok, existing condition

Our public plazas, courtyards and parks could be a more pleasant to relax, engage and have fun in a natural environment without these barriers…

Figure 10: Public garden, Dundas Street Mongkok; existing condition and an alternative view

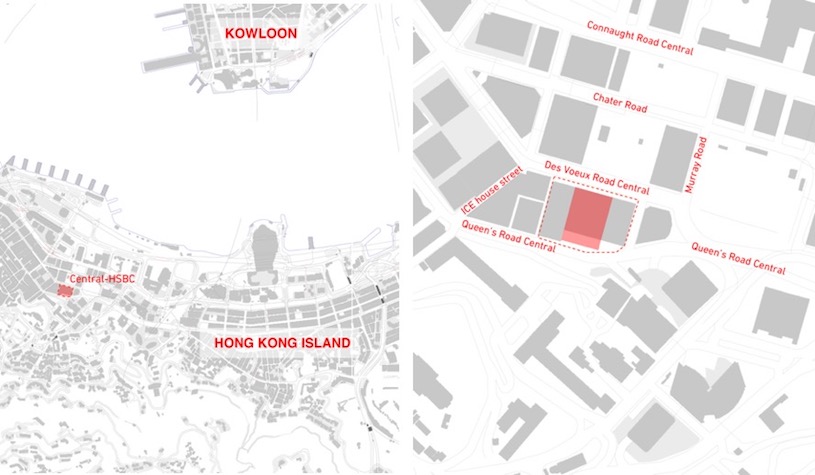

4. HSBC Tower Entry Plaza, Central District, Hong Kong

Type: Covered Plaza

Management: Private Owner

Figure 11: HSBC Tower, Central district, location plan

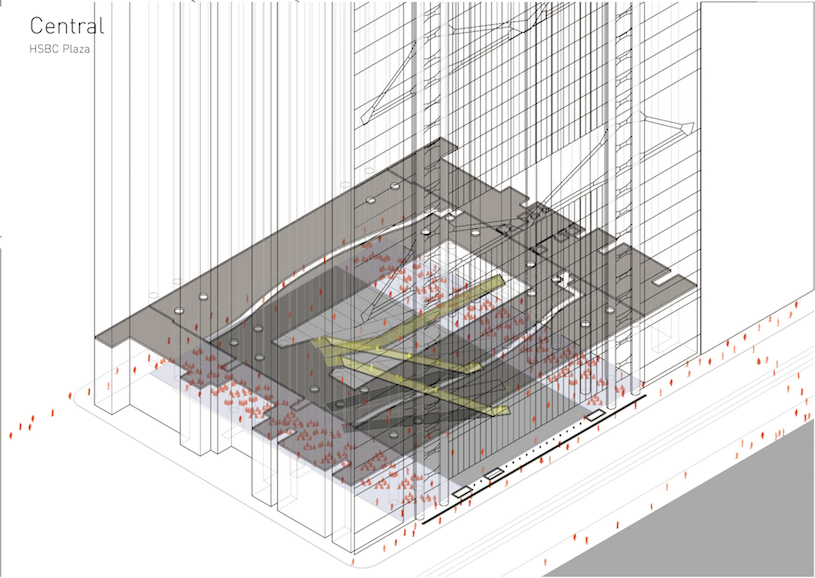

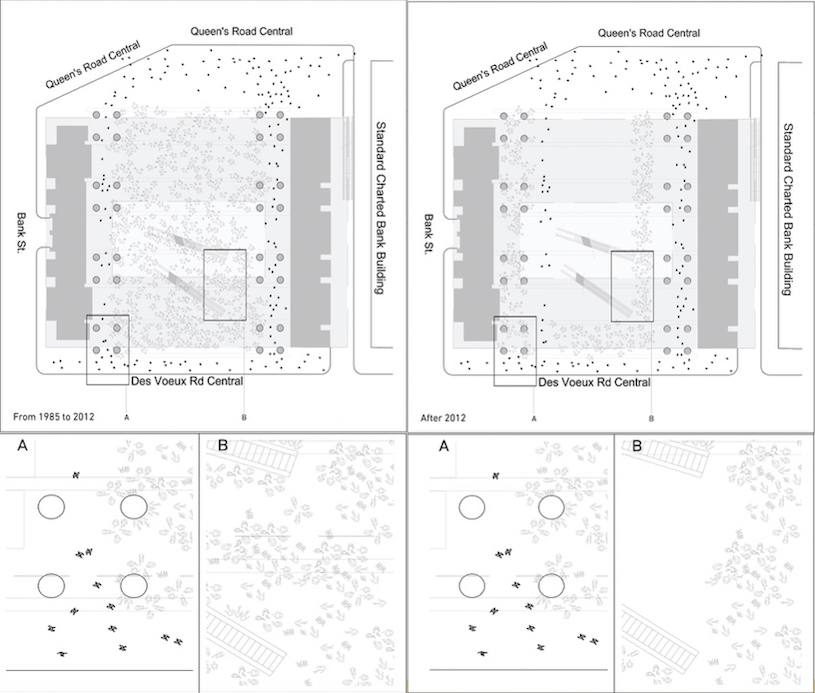

The HSBC Tower in the Central District of Hong Kong is an icon of contemporary architecture designed by Norman Foster in 1985 and located along the southern side of Statue Square, near the location of the old City Hall. This covered courtyard has become a popular gathering space for foreign domestic helpers on their Sunday rest day and on public holidays. In this plaza and across Hong Kong there are thousands of foreign domestic helpers making use of cardboard and plastic sheeting to create pockets of privacy within sheltered areas of public and quasi-public space; a new social landscape adjacent to the busy roads and elevated walkways of the city.

Figure 12: HSBC Tower Plaza, existing condition following renovation

Figure 13: HSBC Tower Plaza, prior to renovation

Figure 14: HSBC Tower Plaza; detailed plans showing occupation before and after renovation

Figure 15: HSBC Tower Plaza, prior to renovation

Figure 16: HSBC Tower Plaza, following renovation

In response to this physical and environmental restriction, a series of green umbrellas could offer enclosure and shade for these temporary territories and provide an evolution of this peculiar cultural phenomenon.

Figure 17: HSBC Tower Plaza; street and public space design proposal

Discussion

Jacob (1961) and Newman (1973) are two of many that explain the relationships between the design/planning quality and the actual quality of public space for the users and residents. Although under-management or over-management have been understood to be the main reasons for the decline in the public space, it seems that the main reason for public space decline lies in the principles and approaches to the ‘production of space’, where production of a socio-cultural space is achieved through maximizing of the functionality with an aim to increase the absorption of the masses and to encourage the diversification of the spatial user groups. In designing public space, it is important to consider the desired social outcomes and how the physical space and its context will or will not support them.

Considering the desired social context in Hong Kong, it is important to be realistic about what sort of space can or cannot be created, and what will work and what will not in particular locations. The success of public spaces depend on three interconnected spatial concepts; a robust design approach (physical space), a level of social activity (social space), and sustenance and evolution in the value of locality and identity (mental space). A key to this robustness in not in fixity but in a flexibility to adapt and change over time in a manner that can respond to the needs of an evolving community whilst withstanding the pressure towards homogenisation so that these spaces feel distinct, welcoming and rooted in the local context.

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

Figures

All photographs and images taken and produced by Dr Hee Sun Choi and Eason Yeung (© all rights reserved).

Figure 1: Public space regulation and management

Figure 2: Four study areas

Figure 3: The backstreets of North Point

Figure 4: Animated sectional view showing the character of the backstreet adjacent to Java Road

Figure 5: Swatow Street location plan

Figure 6: Swatow Street sitting out area, after two phases of renovation

Figure 7: Swatow Street sitting out area, before and after renovation

Figure 8: Public garden, Dundas Street Mongkok, location plan

Figure 9: Public garden, Dundas Street Mongkok, existing condition

Figure 10: Public garden, Dundas Street Mongkok; existing condition and an alternative view

Figure 11: HSBC Tower, Central district, location plan

Figure 12: HSBC Tower Plaza, existing condition following renovation

Figure 13: HSBC Tower Plaza, prior to renovation

Figure 14: HSBC Tower Plaza; detailed plans showing occupation before and after renovation

Figure 15: HSBC Tower Plaza, prior to renovation

Figure 16: HSBC Tower Plaza, following renovation

Figure 17: HSBC Tower Plaza; street and public space design proposal

References

Adam, P. (2010) Public Space Development in the contect of urban and regional resilience, Jouranl of Economics and Management, 10: 47-58

Fincher, R. and Jacobs, J. M. (1998) Cities of Difference, The Guildford Press, New York and London

Gehl, J and Gemzoe, L (1996) Public Spaces Public Life (Copenhagen 1996), Danish Architectural Press

Jacob (1961) Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random House

Lefebvre, H. (1992) The Production of Space, translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith, ‘perceived space’ of everyday social life, John Wiley and Sons Ltd

McDowell, L. (1997) Capital Culture: Gender at Work in the City, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd

Newman, O. (1973) Defensible Space, Architectural Press, London

Nemeth, J. (2012) Controlling the Commons: How public is public space?, Journal of urban affairs review, 48(6):811-835

Shields, P. M. (2004) Classical Pragmatism: Engaging practitioner experience, Journal of Administration and society, 36(3):351-361

Whyte, W. (1980) The Social Life of Urban Spaces, Project for Public Spaces, New York