Introducing Vertical urbanism in Europe

This issue of Built Environment seeks to contribute to emerging debates around vertical urbanism by emphasizing the recent sharp upward trajectories of European cities. The skylines of London, Paris, Madrid, Milan, or even Saragossa and Malmo have been transformed dramatically by new tall buildings. This resurgence of skyscrapers that began in the early 2000s is a major phenomenon, both intense and widespread. In Greater London alone, more than 300 tower projects are proposed, while in Madrid, the Chamartín district has become home to the eponymous four towers of the Cuatro Torres Business Area. Barcelona has also undertaken vertical urban renewal at Fira de Barcelona (around Gran Via) and Diagonal Mar. On the other side of the Alps, Milan has been gracing the covers of specialist journals following the construction of the Bosco Verticale, dubbed the world’s first ‘vertical forest’, while in the north, Stockholm is experiencing its first timber framed skyscraper.

Image 1: Unité d’Habitation, Berlin, Germany, M. Appert, 2009

This post-2000 boom is not necessarily exemplified in super-tall futuristic structures such as the ones that have been erected in Dubai or Beijing during this period, but in supposedly compact energy-efficient urban blocks according to new high-rise urbanism principles. Woven into the existing city fabric, these projects are often framed from the ground up, as initiatives to reinvigorate local deprived or de-industrialized neighbourhoods and to create urban amenities around transport nodes, embodying new sets of discourses and practices among built environment professionals and planning authorities.

Image 2: Potsdamer Platz, Berlin, Germany, M. Appert, 2009

Of course, towers are not new in European cities. The continent occupies a special place in the modern history of vertical urbanism. While European industrial architectural and engineering research inspired the construction of the first skyscrapers in the United States, North American vertical architecture became in turn a key reference for post-War European planners in modernising urban centers. However, contrary to its North American model, European post-War vertical urbanism was crucially characterized by a culture of large-scale urban planning which was mainly the product of highly centralised forms of state intervention, a configuration that helped create distinctive types of European high-rise housing.

Image 3: Birmingham skyline, UK, M. Appert, 2008

Today though, high-rises are more associated with centrality and distinction, be it for companies that finance, build and occupy them or for residents that benefit from spectacular views and good accessibility. From London to Paris and Vienna, the protected skylines of European cities have been troubled in the last fifteen years by new waves of tall buildings. This has given renewed strength and new urgency to heritage and conservation groups and lobbies who strongly oppose new skyscrapers. From opposition to the Gazprom Tower in St Petersburg to the Tour Triangle in Paris and many residential blocks in London, this is prompting the need to closely examine the conditions of the emergence of a renewed European urban vernacular of contemporary high-rise urbanism.

Listing & Image 4: Madrid new skyline, 2009, M. Appert

Through a combination of particular case-studies across Europe with wider analyses of national and international trends, this special issue investigates the relationship in European cities between high-rise built fabric and planning regimes, financial flows, cultural representations, technical innovations, and forms of modernist heritage. Developing cross-disciplinary perspectives and engagement with both academic and practitioner insights, the issue provides a sustained assessment of high-rise Europe in the context of a wider world of vertical urbanisms.

Considering this diversity of contemporary forms of high-rise urbanism, our special issue of Built Environment opens up a range of practices and manifestations across Europe according to three main perspectives: political economy, heritage and planning and symbolic landscapes. The first four papers explore how European cities are located on the emerging global map of investment flows and trace back the genealogy of entrepreneurial forms of verticalisation which started in 1970s. The second group of papers show that contrary to the modernist era, where high-rise clusters were the result of strong planning regulations and paradoxically related more to the urban fabric of historical cities, current high-rises are developed with loose strategic guidelines. Finally, the last four papers of the issue investiagate how changing symbolic landscapes and cultural representations of high-rise urbanism in contemporary Europe need to be mapped directly onto new class relations and trajectories of neoliberal urbanism, as exemplified by the circumstances that fuelled the horrific Grenfell Tower tragedy in London in June 2017.

Considering this diversity of contemporary forms of high-rise urbanism, our special issue of Built Environment opens up a range of practices and manifestations across Europe according to three main perspectives: political economy, heritage and planning and symbolic landscapes. The first four papers explore how European cities are located on the emerging global map of investment flows and trace back the genealogy of entrepreneurial forms of verticalisation which started in 1970s. The second group of papers show that contrary to the modernist era, where high-rise clusters were the result of strong planning regulations and paradoxically related more to the urban fabric of historical cities, current high-rises are developed with loose strategic guidelines. Finally, the last four papers of the issue investiagate how changing symbolic landscapes and cultural representations of high-rise urbanism in contemporary Europe need to be mapped directly onto new class relations and trajectories of neoliberal urbanism, as exemplified by the circumstances that fuelled the horrific Grenfell Tower tragedy in London in June 2017.

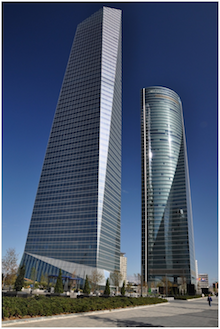

Image 5: Torre Espacio and Torre de Cristal, Madrid, 2009, M. Appert

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

Image 1: Unité d’Habitation, Berlin, Germany, M. Appert, 2009

Image 2: Potsdamer Platz, Berlin, Germany, M. Appert, 2009

Image 3: Birmingham skyline, UK, M. Appert, 2008

Listing & Image 4: Madrid new skyline, 2009, M. Appert

Image 5: Torre Espacio and Torre de Cristal, Madrid, 2009, M. Appert