Regulating Informality: spaces of everyday consumption in Riyadh

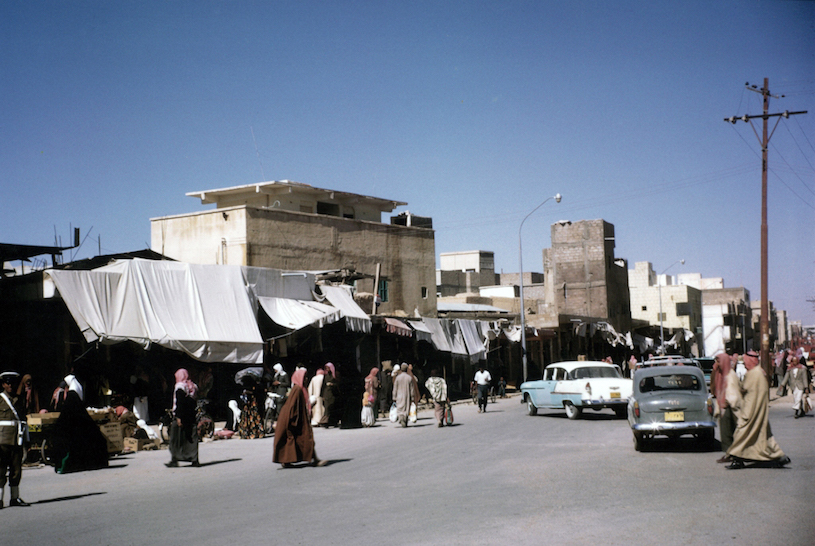

Figure 01: A typical market scene in 1960s Riyadh (Source: Keith Wheeler)[1]

The old centre of Riyadh is a charming place, recalling a past age of narrow alleyways, souks, and popular (Sha’abi) restaurants. It still retains many of these qualities – in the district of Batha or near the Qasr al Hokm area for example. Markets are thriving and there is an active urban development scene. And yet some pockets are in a state of decay. Walking through these well-worn pathways suggests an authenticity, beloved by urbanists, because of the presence of various layers of history and evidence of the passage of time. An urban palimpsest. The spaces of old Riyadh represent a counterpoint to the modern city with its gleaming skyline and fancy shopping malls. Charm notwithstanding, the old city also attracts informal use. Some of its sidewalks are occupied by fruit and vegetable vendors, appropriating some of the street furniture, such as boulders, to display their wares to passers-by. In a nearby plaza there are a few vendors who have set up a table with their merchandise. It all seems rather harmless but it is unregulated and as such constitutes an infringement on public space. It also suggests disorder. And, according to some observers disorder leads to urban blight, while others may argue that it is an essential component of vibrancy.

Figure 02: Fruit and Vegetable Vendors in Riyadh’s Old Center

Urban sociologist Richard Sennett author of the classic The Uses of Disorder elaborates on how allowing for disorder is necessary for a healthy urbanity and the functioning of cities (Sennett, 1970, 2001, 2007). A city – as he argues – needs to embrace diversity and difference; encountering an ‘other’ raises people’s awareness of their fellow citizens. The alternative is a mind-numbing homogeneity. The argument is valid to a degree but there are caveats. Indeed, the unequivocal embrace of disorder may lead to chaos. If left unchecked parts of a city can be overrun with informality which can very easily result in urban decay and other urban ills. For example, in some parts of Cairo informal markets and vendors dominate public spaces to the extent that sidewalks are no longer used for walking and traffic is blocked due to the presence of carts selling all sorts of stuff.[2] It is easy to romanticize disorder and associate it with some sort of urban vitality but there are clearly limits that need to be considered.

Many cities regulate use of public space. Food carts, outdoor seating areas and the like are subject to guidelines and specifications, which may vary from one city to the next but they all share the principle of controlling informal use. Singapore’s hawkers’ markets are well known for serving traditional food, prepared in front of customers sitting in an open space that connects to the street. And yet it takes place within a setting that is subject to approval by authorities as well as guidelines pertaining to the observance of proper storage, preparation and the like. In spite that one has the sense of being in a space that is not commodified, or part of a chain. It has an authentic character and as such it has become an essential part of Singaporean culture. Similar settings can be found in other Asian cities such as Bangkok or Hong Kong where sidewalks are sometimes fully occupied by seats and tables served by a small stand manned by a cook. In the midst of such settings informal use proliferates prompting authorities in these cities to crack down to the extent of banning outdoor street preparation and consumption (Dewolf, 2017).[3]

Figure 03: a) Food Stalls in Bangkok; b) Vegetable Market in Singapore’s Little India; c&d) Produce vendors in the midst of Hong Kong high-rises

New York City is famous for its food carts, serving Hot Dogs, Kebab, Shawarma and Falafel. They suggest a certain informality, an impromptu arrangement of food consumption that allows for a more down-to-earth experience. However, their use is highly regulated. An official 68-page document issued by the City of New York titled ‘Rules and Regulations for Mobile Food Vending’ provides very specific guidelines related to the activity. This includes restrictions on where to place street carts, obtaining licenses, food storage procedures, disposing waste and much more.[4] However, the enforcement of rules is erratic and inconsistent. Thus, as the New York Times reports ‘it’s nearly impossible (even if you fill out the right paperwork) to operate a truck without breaking some law’.[5] This adds to a certain form of ‘controlled disorder’. An interesting case involves South American migrants who operated open air food stalls in an informal atmosphere at Brooklyn’s Red Hook Ball fields. This informal selling of food resembled an atmosphere of a central American mercado or market. Eventually authorities required an accommodation of sanitary regulations. Food had to be sold from trucks and everyone involved in the activity needed to acquire a license. This prompted some urbanists to decry the loss of authenticity since it formalized the interaction between buyer and seller (Zukin, 2010). However, vendors continued to operate demonstrating how food consumption played an important role in providing an authentic urban experience.

Riyadh has its share of historic markets as noted earlier. Over the years however much of that changed. Retail activities moved indoors to specialized shopping centres, malls and food courts. The purchase of food has become part of a corporatized structure making it anonymous and less personalized. And yet in spite of this change the informal still persists indicating a strong desire to move beyond packaged presentations and to purchase products directly from the people who produce them. There is also the matter of convenience: walking out of your residence and finding a market nearby or stopping a car along the highway to purchase some fruit is a desired urban condition. During my visits to Riyadh over these last few months I had the opportunity to witness a variety of different informal activities. For instance, two Saudi vendors set up a table and a coal grill on which they brewed tea serving customers on the fancy Tahlia Street (see my previous blog ‘Three Days in Riyadh’); a similar setup existed on the walking paths around Prince Sultan University. Along Suwaidi Park, by the side of the road I observed a tea stand selling the beverage to passing cars; it was late at night and the vendors were sitting along the fence of the park, with a small fire lit to keep warm. All of these were highly incongruous sights given the upscale surrounding but were accepted. They provided a comfort of sorts, a service that was welcomed by residents allowing them to purchase a simple drink without having to patronize some corporate conglomerate. Informal arrangements can be found in numerous parks and walking paths as documented in previous blogs. The proliferation of food carts is a formalization of this process and has become popular over the last few years. Driving along the city’s multiple highways one may encounter pickup trucks that sell the local Arabian version of truffles, faqa’a; other cars sell fruit and vegetables. Such vendors also operate in low-income districts such as Hay al-Wizarat and even in the old centre of Riyadh, near the venerable Qasr al-Hokm.

Figure 04: A juice vendor at the entrance to Prince Abdulaziz bin Ayyaf park

Figure 05: A produce vendor in Riyadh’s Wizarat district

The presence of such informal activities imbues Riyadh with a distinct character. The activity also has some economic benefits as it helps low-income residents and is an important source of income as was outlined in a detailed report in the local media.[6] However they are also problematic as they attract illegal migrants, block traffic and are not subject to any health regulations. The former mayor of Riyadh, Prince Abdulaziz bin Ayyaf, recognized this problem as he articulated in a response to one of these reports.[7] However rather than simply eliminating the practice, he developed a process through which informal retail could be integrated into the formal economy through a set of spatial interventions that proved to be very effective in reducing the phenomena, while maintaining the spontaneity of interaction between merchant and customer.

Riyadh municipality under the guidance of its former mayor thus introduced a series of measures recognizing that informal vending serves an important function while also being in line with best practices in other major urban centres throughout the world. To that effect the humanization efforts entailed a series of initiatives including one pertaining to ‘consumer protection and stimulating traditional markets’. This comprises several categories such as establishing a price index initiative and setting up street vendors regulations. Specific spatial interventions were introduced to accommodate this change in policy. During my visit in the Spring 2019 I experienced a series of projects that were an outcome of the municipalities humanization initiative. These included municipal vendor plazas; a farmer’s market; and a centre for the sale of used goods. All of these display a recognition of informality and are a serious attempt to regulate the activity while maintaining its spontaneous and immediate character.

With respect to street vending, assigning free locations to conduct the activity was a main part of legalizing their status operating under the principle of ‘supporting and stimulating street vendors rather than leaving them vulnerable to police pursuit and confiscation’ (Bin Ayyaf, 2017, p. 100). One of these is off Khureis Road, in Riyadh’s far east, in the Nazim district which is comprised of non-descript two-storey villas, typical of the city’s suburban landscape. At the entrance to the neighbourhood is a tent-like structure that is designed to be a special area or plaza (mawaqif) for roaming vendors (ba’a mutagawilin) who sell fruit and vegetables. A large sign specifies rules for using the plaza: it is for Saudis only; opening hours are after the dawn prayer (fajr) till sunset (maghrib); space availability is based on a first come, first serve basis; cars and tables can be used for the display and sale of merchandise but must be removed at the end of the day; and use is free. Significantly one of the instructions notes that this is a temporary structure and therefore any alteration or additions to the plaza are not permitted. As I walked in the midst of the vendors, it was midday so activity was relative sparse, but there was an abundance of products. There were also signs of extensive use – wall cracks, graffiti, chipped paint – suggesting that this is a space that has been around for a while and has become part of the everyday landscape of the surrounding neighbourhood. It evoked a sense of normalcy and, significantly, an activity that would have typically taken place on highways has now been centralized in a well-known location making the purchase of products easier and more convenient. Throughout Riyadh there is a series of such small plazas. There is also a much larger project serving small farmers who are part of an increased focus on organic agriculture and the Kingdom’s strive to achieve self-sufficiency in food production.[8]

Figure 06: Scenes from the ‘roaming vendors plaza’ in Northern Riyadh

Such markets tap into a growing awareness by consumers on healthy living and consumption of food that is free of pesticides – a reflection of trends elsewhere in the world (e.g. Parham, 2015). In Riyadh, Souq al Shamal (the northern market) is a massive area that includes fisheries and various spaces for selling produce. The municipality in 2009, recognizing the need of small farmers, set aside a special day and an area within that market so that they can sell their products directly to consumers. The setup was initially a simple open space which was then further developed with a dedicated structure. Inspired by traditional Najdi architecture, the enclosure provides shade and a large sales area. Both entrances from either side allow for further display of items. During my visit in the Spring of 2019 indoor and outdoor areas were boisterous and filled with activities. People from varying backgrounds, male and female, frequented the various stands. Teenagers were operating carts to assist customers in carrying their purchases. Signs of extensive usage were in evidence, which included graffiti attesting to the market’s popularity. The atmosphere was quite informal with some traders engaging in various acts to entice and attract customers to what they were selling. Media accounts have celebrated the project noting that on its opening day more than 60 farmers were selling products and that there were between four to five thousand visitors per week. They dubbed the project ‘youm al-wanit al-ahmar’ (the day of the red van, the truck on which products would typically have been sold).[9] Spaces are provided free-of-charge under the supervision of the municipality who ensure that hygienic practices and standards are maintained.

Figure 07a,b,c: ‘Farmers Day’ market taking place every thursday

Aside from food activities there is also a thriving trade in used goods of all kinds which has a long history harking back to the 1950s in a market known as Hiraj Beni Qasim, one of the largest markets for used items in Saudi Arabia. There, goods are traded using a traditional process of auctioning (haraj). In 2015 the market was transferred from its old location, following complaints about its deterioration and presence of illegal acts such as selling of stolen goods, to a location south of Riyadh. The project was a partnership between the municipality and The Riyadh Development Holding company. In its current capacity it represents a major transformation by providing appropriate platforms for displaying goods (mabasit) in addition to allowing the continuation of the auctioning (haraj) process carried out by a designated auctioneer (muharij) who uses customary phrases to entice potential customers. I had the opportunity to witness an auctioning activity. A truck carrying items ranging from pots and pans, silverware, electronics, carpets – literally a grab bag of stuff – arrived and disbursed its load on a platform. Then it was appropriated by an auctioneer who began shouting an initial price (1,000 rials; about 300 USD). A large group of people gathered inspecting the items while listening to incessant calls to purchase and take advantage of this unprecedented opportunity. Ultimately a sale was made and the bounty carried away to a waiting car. Witnessing this I came to realize that an intrinsic aspect of Saudi culture has been preserved but also modernized to be in line with contemporary practices and regulations.

Elsewhere in the market, an open-air structure, modern in its appearance and occupying an area of about 300,000 m2, things were a bit calmer. Row after row of open display units (mabasit) contained used clothes, antiques, electronic devices and more. There were also shops that sold used and new furniture, all frequented by people eager for a deal. We were there mid-week and in the middle of the day, so activity was a bit sparse. But I was assured that at the weekends the rush of people is such that it is difficult to walk in the various passageways. Nearby the old market still stands, showing clear signs of deterioration and decay. The streets were empty and at the edge of the area is an open space – now completely abandoned; this is where the process of haraj would take place. In a clear sign that things have changed, a signboard by the municipality overlooks the site, which states that under no circumstances can any auctioning take place here and that the market has moved to its new location. Those looking to revive the days of the past must venture to the new locale.

Figure 08: Scenes from Haraj beni Qasim, used items auctioning and sales center

Cities thrive through the informal (or the appearance of the informal). Rather than being in anonymous, globalized, and corporatized shopping malls which look the same wherever one goes anywhere in the world, informal spaces allow for encountering an unexpected experience. This enriches our lives making it more interesting. The informal relies on sociability and accommodates people from all walks of life. In this way it may also encourage inclusivity. But throughout the world the desire for change and improvement is clear. Tokyo’s ancient Tsukiji market is a wholesale fish market where fish is auctioned, bought and prepared for customers (Bestor, 2004). It has recently been transferred from its old and much beloved location to a newer place far from the city. Many have decried such a move arguing that it has deprived Tokyo of a traditional and essential aspect of its culture.[10] But culture and tradition are not necessarily fixed constructs. Indeed, the city is looking to the future, preparing to host the upcoming Summer Olympics in 2020 and is using the site of the old market for that purpose. The traditional is ever-changing and adaptable; otherwise cities risk turning into fossilized versions of their past, standing still in the face of progress.

It is, however, important to also recognize that people lie at the heart of any modernization effort and development. Empathy towards those less fortunate is an important aspect of city governance. Riyadh in its striving for regulating informality, which represents the core of its humanization initiative, has recognized this. First steps have been made successfully and a process set in motion. This needs to expand and pervade every neighbourhood. Riyadh can then be truly a city where people are placed front and centre – a city that both embraces its past and looks forward to the future and, most importantly, does not succumb to the seductive allure of speculation or relying solely on financial profits and real estate investment.

References

Bestor, T.C. (2004) Tsukiji: The Fish Market at the Center of the World (Vol. 11). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Bin Ayyaf, A. b. M. (2017) Enhancing the Human Dimension in Saudi Municipal Work. Riyadh, A Paradigm. Riyadh: Tarah International.

Dewolf, C. (2017) Borrowed Spaces: Life Between the Cracks of Modern Hong Kong. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Parham, S. (2015). Food and Urbanism: The Convivial City and a Sustainable Future. London: Bloomsbury.

Sennett, R. (1970) The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity & CityLife. New York: Knopf.

Sennett, R. (2001) A flexible city of strangers. Le Monde Diplomatique.

Sennett, R. (2007. The open city, in Burdett, R. and Sudjic, D. (eds.) The Endless City. London: Phaidon, pp. 290–297.

Zukin, S. (2010) Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

All images copyright of author, unless otherwise stated.

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

[2] Kimmelman, Michael (2013) Who Rules the Street in Cairo? The Residents Who Build It. The New York Times, April 27.

https://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/28/arts/design/in-cairo-rethinking-the-c...

[3] South China Morning Post (nd). Closing time. How Hong Kong’s hawkers face a struggle to survive http://multimedia.scmp.com/hawkers/; Petersen, Ellis (2018) ‘It's a shocking idea’: outcry over Bangkok street vendor ban. The Guardian, August 4. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/aug/04/bangkok-street-vendor-ban-prompts-outcry-thailand

[6] Al-Riyadh (2005) Roaming vendors … citizens prevailing in the face of poverty. March 31. http://www.alriyadh.com/52437#

[7] Al-Riyadh (2005) The practice of roaming vending is a clear violation to regulations. April 11. http://www.alriyadh.com/55709#

[8] Organic Agriculture in Saudi Arabia. 2012 Sector report. Department of Organic Agriculture.

https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2012-organic-agriculture-saudi-arabia...

[9] Al-Riyadh (2009) Farmers Day. The red wanit which transformed into a national initiative north of Riyadh. May 14. http://www.alriyadh.com/429230

[10] Searless, Harrison (2019) What Tokyo’s Tsukiji Fish Market Teaches Us About Urban Planning. January 4. The American Conservative. https://www.theamericanconservative.com/urbs/what-tokyos-tsukiji-fish-ma...