The Biennale that Never Was

This was supposed to be the people’s biennale. Or at least that was the hope. The event when the architectural profession would finally relinquish its elitist stigma and embrace the downtrodden. Marking a descent from its lofty heights to the ‘spaces down below’ where the majority of the forgotten populace actually lives. But, alas the 15th architectural iteration of this elite event missed a chance to mark a point of departure from business as usual. In spite of the lofty rhetoric concerning the social consciousness of architecture, the challenge to the status quo, and the focus on exotic places – the overall impression is, to put it mildly, underwhelming (others noted that it did not ‘pass muster’).

Curiously though, for the most part the tone of many reviews has been celebratory with some arguing that is as good as the 2014 version by Rem Koolhaas (assuming that this was some sort of glorious benchmark).[i] Many acknowledged the limitations of architecture in the face of problems facing mankind, while in all seriousness lauding Aravena, this year’s director, who ‘rather than opt for crowd-pleasing spectacle … forged ahead with a more weighty brief’. One of its most outspoken critics – Patrick Schumacher (of Zaha Hadid fame) – actually called for the Biennale to be shut down because it ‘confuses the public’. He makes an interesting point but for all the wrong reasons. On the face of it gestures have been made towards addressing some of the issues raised by Alejandro Aravena in his aptly titled theme ‘Reporting from the front’. The confusion arises however because most of this year’s output more or less revolves around the ‘master architect’ who dispenses his nuggets of aesthetic wisdom to the disenfranchised (when s/he actually deems them worthy of intervention). In many ways this does not deviate that much from the typical top-down approach characterizing the profession[ii].

Image 1: The architect as master builder confronting the world, in The Fountainhead (1943)

Image 1: The architect as master builder confronting the world, in The Fountainhead (1943)

Perhaps the one moment that perfectly captures these sentiments is the widely circulated image of the opening day panel. All-white-male experts – including the holy trinity of Aravena, Foster and Koolhaas – sharing the stage and discussing infrastructure. And this in a supposedly socially conscious Biennale that seeks to redress inequality through architecture.

Image 2: Opening day panel at the Venice Architecture Biennale

Image 2: Opening day panel at the Venice Architecture Biennale

This should come as no surprise though since Aravena’s own work demonstrates the complicity of architects in furthering neo-liberal economic visions. For example, his much revered and celebrated, half-finished houses constructed in Chile. Portrayed as an ingenious solution to social housing it provides inhabitants with half a house, the other half of which could be finished at the occupants leisure whenever his/her finances (or needs) necessitate. The houses themselves are aesthetically exciting since the architect created a series of frames which are half-filled. At a later time these gaps are filled. This allows for some fascinating imagery filling the pages of glossy architectural magazines. However many have pointed out that Aravena is not the first architect to use such an approach. Indeed in South America anywhere between 40 to 70% of new construction is unfinished. Moreover these developments are not done by the state but by private developers, including Empresac Copec the Chilean Oil Company controlled by the Angelini family – prompting one observer to question how ‘can a true critique emerge from a position of complicity?’[iii] In such a manner the issue of social housing, typically a prerogative of the state, is taken over by corporate clients – instead of a change in ownership structure and financing, house dwellers are confronted with massive debt. A privatization of social housing. Instead of being a right it has become an act of charity.[iv] Social housing in the service of capital. No surprise that development agencies and neoliberal proponents of urban development see this as the ultimate solution for housing the poor.

The Biennale – being a reflection of the state of architecture today – did not deviate that much from the above. The very selection of projects and themes demonstrates its inherent flaws. Consider the much celebrated brick arch structure dominating one of the exhibit halls. Designed by the Paraguyan architectural office of Gabinete de Arquitectura: it is a soaring example of structural ingenuity using simple traditional materials. The question is though are such complex brick formations really needed in precarious social situations; is a seemingly complex structure an answer to the social needs of communities? Further along is an installation by Transsolar which, through the use of artificial lighting, generated a series of descending light shafts – or ‘lightscapes’ in architectural lingo. Such use of acrobatic lighting effects is more typical in the spaces of soaring museums built in the Arabian desert for discerning art aficionados (e.g. the Louvre Abu Dhabi).

Image 3: Alejandro Aravena addressing visitors and media.

Image 3: Alejandro Aravena addressing visitors and media.

Image 4: The lightscapes of Transsolar, ‘solution’ to the world’s most pressing problems.

Image 4: The lightscapes of Transsolar, ‘solution’ to the world’s most pressing problems.

Other contributions include a proposal by Tadao Ando for the city of Venice, illustrated through a giant life-like model (prompting an irate visitor to mount a flyer on the precious display titled ‘Stop Ando’). And so it goes, one is confronted with a barrage of architectural models, drawings, diagrams and pretentious slogans. Architectural luminaries were represented as well. Norman Foster in some sort of atonement for previous sins delivered an ‘aeroport’ for drones. In remote communities in Africa they are needed to deliver much needed aid. That is good and well – but how does a parabolic structure constructed with local materials, and whose ‘thinness’ is inspiring (as noted by the master himself) useful in this context? Aren’t there more pressing issues at hand (what are the underlying reasons that require drones to be needed in the first place?). These typically do not require a formalist architectural intervention. National pavilions, with exceptions, were no better. From the Spanish pavilion with its celebration of how architects capitalized on unfinished projects (they are still useful it seems in the face of financial doom), to the Peruvian installation which brought ‘architecture’ to the remote corners of the rain forest (why is that a good thing?). And of course the climax was in the much derided US pavilion seeking to show that the solution to Detroit’s problems is in a series of formalistic architectural solutions taken strictly out from a design studio. It comes “at the expense of a more expansive definition of architecture and a deeper urban analysis” and can be construed as ‘… pure formalism posing as social planning’.[v]

Image 5: Foster’s Aeroport facility for drones to be constructed in deprived regions of Africa. Thinness as ‘virtue’.

Image 5: Foster’s Aeroport facility for drones to be constructed in deprived regions of Africa. Thinness as ‘virtue’.

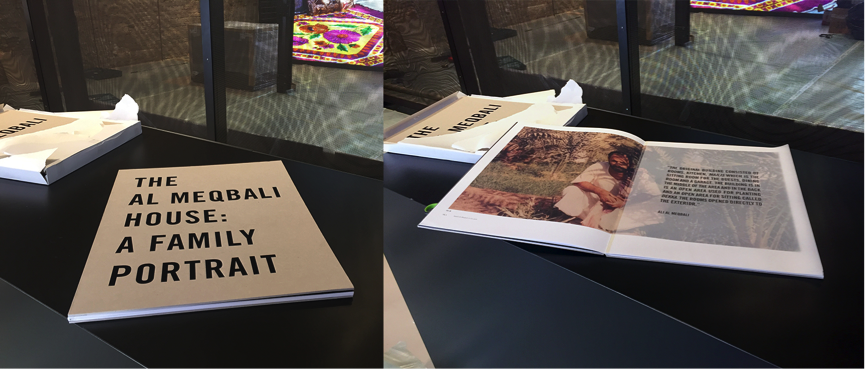

Yet there were exceptions to the spectacle. Some pavilions and curators took the theme to heart aiming to go beyond the limiting confines of an architecture profession so obsessed with itself that it cannot see beyond its own narrow discipline. One of the most profound is the Portuguese Pavilion titled ‘Neighborhood: Where Alvaro Meets Aldo’. Designed as a site-specific installation focusing on Siza’s public housing project in Giudeca, Venice (in addition to three other European cities). Siza is of course a master of modernism and one of the most well-known and respected architects in the world – yet it was absolutely delightful to see him humbled by the visit to the community which he helped create. The exhibition is dominated by a series of videos which show him interacting with residents during a visit that took place prior to the Biennale. Here we encounter the ‘architect’s subjects’ who are no longer abstract entities existing in the imagination of the artist. The architect listens to their concerns, has dinner and drinks with them, all the while smoking and being surrounded by the spaces he designed. Yet architecture here takes a backdrop – it is no longer about forms, exquisite detailing, and acrobatic structures. We witness life as it unfolds and how architecture made a difference to the lives of the people who inhabit these apartments. Juxtaposing Siza with the residents was such a profoundly moving gesture which, in my view, is a perfect response to the theme of ‘Reporting from the front’. There were other home-based pavilions such as Singapore which explores how people modified their homes and their city; or the UAE pavilion – which I curated – that demonstrates the changes made by people to their habitat to make it more suitable to their needs and culture.

Images 6a & 6b: The Portuguese pavilion. A focus on people for a change.

Images 6a & 6b: The Portuguese pavilion. A focus on people for a change.

There were also some pavilions that focused on experiences and how people respond to their environment. The Irish pavilion in particular provided an utterly moving installation that attempted to convey how people with dementia make sense of their surroundings. Titled ‘Losing myself’ it looks at an actual ‘Center for Dementia’ over a period of 24-hours and the extent to which it is experienced by its inhabitants. The focus shifts away from ‘architecture’ and instead an attempt is made to highlight its social function and how it can aid in improving the conditions of people with dementia.

Image 7: The UAE pavilion. De-emphasizing architecture and focusing on habitation. Architecture without architects.

Images 8a & 8b: The UAE pavilion. Highlighting the role inhabitants play in personalizing their surroundings.

The above are exceptions though and it is unfortunate that the Biennale did not have more examples that demonstrate both the power of architecture and that it sometimes needs to be in the background to allow for the unfolding of everyday life. Yet in order for this to happen there needs to be a paradigm shift in the profession. For one thing, architects must embrace other disciplines and work with ‘anthropologists and sociologists and psychologists in the way that they create space’.[vi] As some have pointed out there needs to be a complete overhaul, a ‘radical imagination’ that abolishes the existing order – otherwise ‘it is bound to spatialize, reproduce and distribute the inequalities of capital’.[vii] The alternative is maintaining the status quo, a continuous deification of star-architects further exacerbating and sustaining the inevitable slide towards marginalization, exclusion and ridicule. [viii]

[i] Landon, R. (2016) Aravena’s ‘Reporting From The Front’ Is Nothing Like Koolhaas’ 2014 Biennale—But It’s Equally as Good. ArchDaily, 14 June. http://www.archdaily.com/789409/aravenas-reporting-from-the-front-is-nothing-like-koolhaas-2014-biennale-but-its-equally-as-good

[ii] Regarding ridicule an upcoming mainstream movie (a comedy) is titled The Architect more or less freely ploughing from every cliché that exists about architects – their aloofness, impracticality, disregard for others and so on – this is how the rest of the population sees us! The tag line reads: ‘When a couple sets out to build their dream house, they enlist the services of a visionary modernist architect, whose soaring ideas are matched by only his ego. The woman is swept away by the uncompromising creative artist whose personality provides a stark contrast to her practical husband’s. She is so taken she hardly notices the Architect is building HIS dream house.’ https://vimeo.com/160949784

[iii] Chan, C. (2016) Conditions of Living. Frieze.com. 17 June. https://www.frieze.com/article/conditions-living

[iv] Namias, Olivier (2016) Privatised Solution to Public Housing Inequality; Half a Good Home Isn’t enough. Le Monde Diplomatique, 04, English edition.

[v] Menking, W. (2016) Is the U.S.’s Biennale Pavilion actually the Quicken Loans Pavilion? The Architect’s Newspaper, 20 June. http://archpaper.com/2016/06/us-biennale-pavilion-2019-review/

[vi] The good, the bad and the built: why architects should put people first. The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 June 2016. http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/the-good-the-bad-and-the-built-why-architects-should-put-people-first-20160614-gpht7a.html

[vii] Swyngedouw, Erik (2016) On the Impossibility of an Emancipatory Architecture: The Deadlock of Critical Theory, Insurgent Architects, and the Beginning of Politics, in Lahji, Nadir Z. (ed.) Can Architecture Be an Emancipatory Project. Winchester: Zero Books. Cited in: Chan, C. (2016) Conditions of Living. Frieze.com. 17 June. https://www.frieze.com/article/conditions-living

[viii] Till, J. (2016) The Architecture of Good Intentions. Reading Design. http://www.readingdesign.org/good-intentions

________________________________________________________________

Image References

Image 1: The architect as master builder confronting the world. Still from the movie version of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead (1943) (Source: screenshot under standard YouTube licence from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vDI-afx6ejk)

Image 2: Image 2: Opening day panel at the Venice Architecture Biennale (Source: photo by Fabienne Hoelzel, Die Architektin, Reporting From Which Front? Aravena’s Sexist Opening Panel https://architektin.files.wordpress.com/2016/05/13322125_1130571540317411_7827721278342027408_n.jpg?w=960 )

Image 3: Alejandro Aravena addressing visitors and media (Source: author © Y.Elsheshtawy)

Image 4: The lightscapes of Transsolar, ‘solution’ to the world’s most pressing problems (not!). (Source: author © Y.Elsheshtawy)

Image 5: Foster’s Aeroport facility for drones to be constructed in deprived regions of Africa. Thinness presented as ‘virtue’. (Source: author © Y.Elsheshtawy)

Image 6a & 6b: The Portuguese pavilion. A focus on people for a change. (Source: author © Y.Elsheshtawy)

Image 7: The UAE pavilion. De-emphasizing architecture and focusing on habitation. Architecture without architects. (Source: author © Y.Elsheshtawy)

Image 8a & 8b (also listing image) : The UAE pavilion. Highlighting the role inhabitants play in personalizing their surroundings. (Source: author © Y.Elsheshtawy)

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme! Do you want to review an event, a book or an exhibition? Then contact us at [email protected]