Is Australia a Suburban Nation?

Rob Freestone’s wonderful book Urban Nation: Australia’s Planning Heritage (CSIRO, 2009) is probably the best survey of Australia planning history, but its title may be misleading today. Australia was certainly an urban nation as early as its first national census in 1911, if “urban” simply meant “not rural”. However, since World War II, much of Australia’s population growth has been accommodated in a peculiar form of urbanism most widely shared with the United States and Canada: low-density, automobile-dependant suburban development.

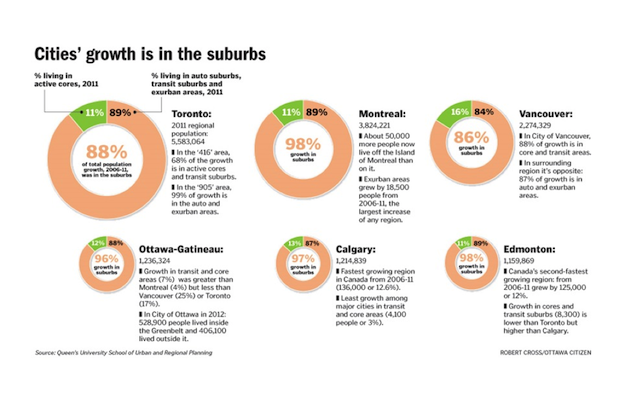

My research indicates that two-thirds of Canada’s total population lived in these suburbs, and approximately 85% of the population of its 33 metropolitan areas lived in suburbs or exurbs (Gordon & Janzen 2013; Gordon & Shirokoff 2014). Few were amazed to learn that many Canadians lived in suburbs, but the size of the majority surprised people, perhaps because the boom in high-rise condominium apartments in central Toronto and Vancouver is so highly visible compared to the low-density expansion of the metropolitan edges.

Worse, most of the Canadian population growth was occurring in these low-density suburbs.

So Canada is definitely a suburban nation, and it doesn’t look like it will be changing in the near future.

Is Australia also a suburban nation? I was curious about the nature and extent of Australia’s suburbs because Newman and Kenworthy demonstrated that Canadian and Australian cities are most similar to each other in the data analysis for their latest book (2015). We began to test the hypothesis with University of Western Australia colleagues Paul Maginn and Sharon Biermann in 2015, trying some of the methods piloted in Canada.

Although there are widely-used definitions for the rural-urban split, there are no consensus definitions for suburban areas and many different proposals for how they might be classified (Forsyth 2012). We were looking for methods that could use data that was universally available through the national census and would produce credible results in both large and small metropolitan areas across the nations.

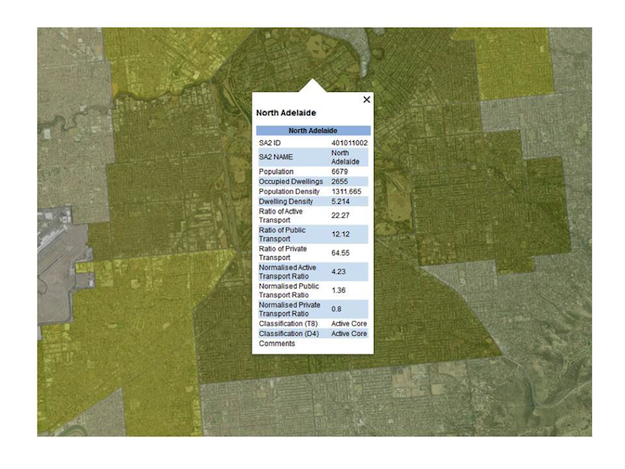

Above: Australian Bureau of Statistics 2011 census data for an Adelaide neighbourhood connected with ArcMap, Google Earth and Google Street View for fact-checking a classification.

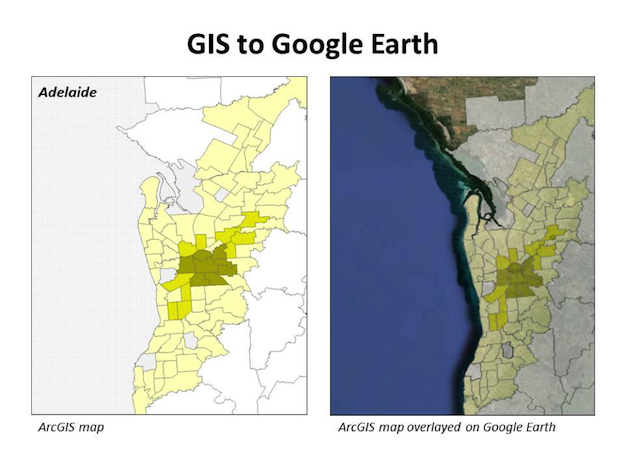

Above: ArcGIS map of Adelaide neighbourhood classification overlaid on Google Earth for evaluation

The method that worked best in Canada (Gordon & Janzen 2013) also produced the most credible results in Australia (Gordon, Maginn & Biermann 2015), classifying neighbourhoods using transportation modal share data for the 16 largest metropolitan areas.

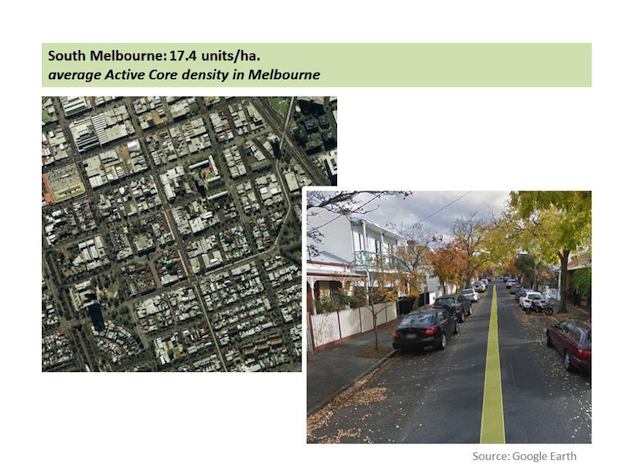

When we started the Canadian research, I expected that the classification would be based upon some combination of built form or building density. To our surprise, the indicator species for an Active Core neighbourhood (what we used to call “inner-city” in the pre-polycentric era) was not a high-rise apartment building, but a pedestrian or cyclist on the journey to work. This should not have surprised us, since there are plenty of dense urban neighbourhoods without high-rise apartments in both countries (i.e. Montréal’s Plateau, or South Melbourne, below)

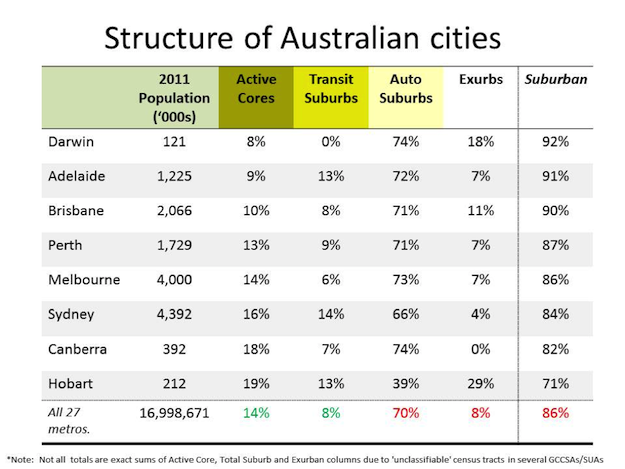

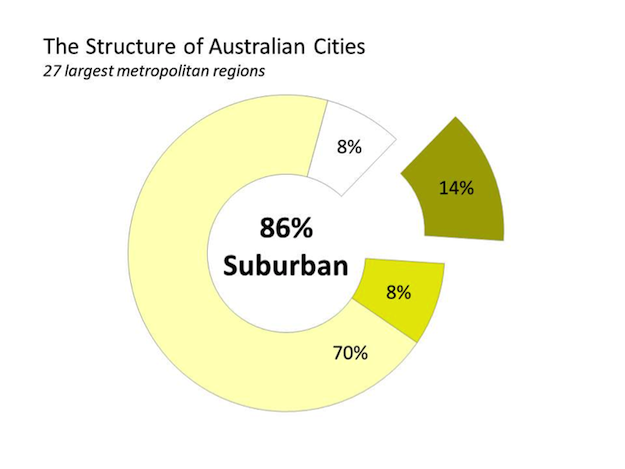

Our analysis of the structure of Australian cities indicates that Australia is indeed a suburban nation. The data for the 27 metropolitan areas shown in the table demonstrates that about 86% of the population is located in suburban or exurban neighbourhoods, a result that is remarkably similar to the Canada.

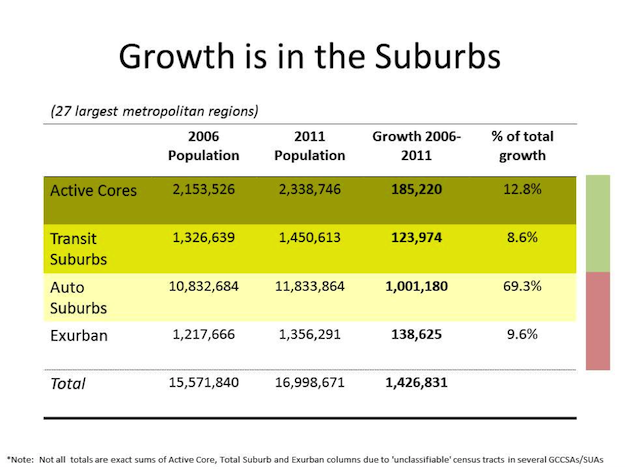

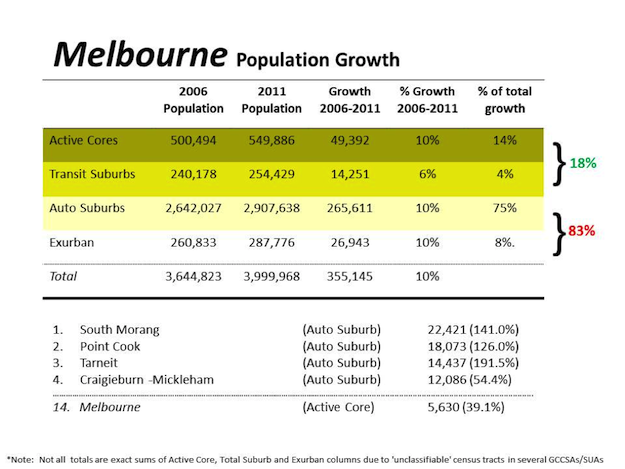

And, despite planning policies that call for intensification and transit-oriented development, a high proportion of Australian metropolitan population growth took place in suburban areas, as can be seen in the tables below. For example, 83% of the Melbourne region’s population growth was located in low-density auto-dependent Exurbs and Automobile Suburbs.

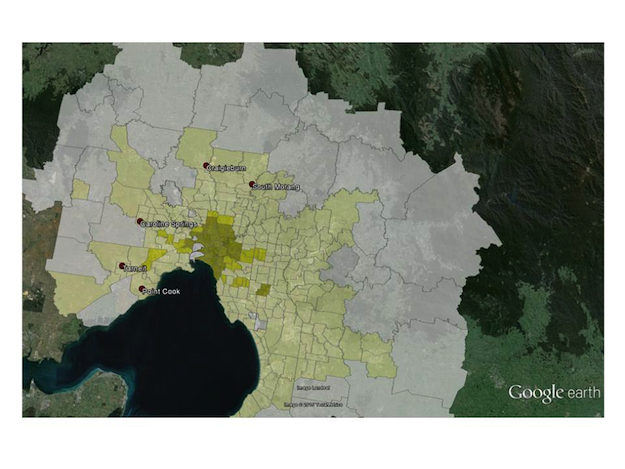

Above: The Melbourne neighbourhoods which grew the most were Auto Suburbs as shown in the Table above and map below

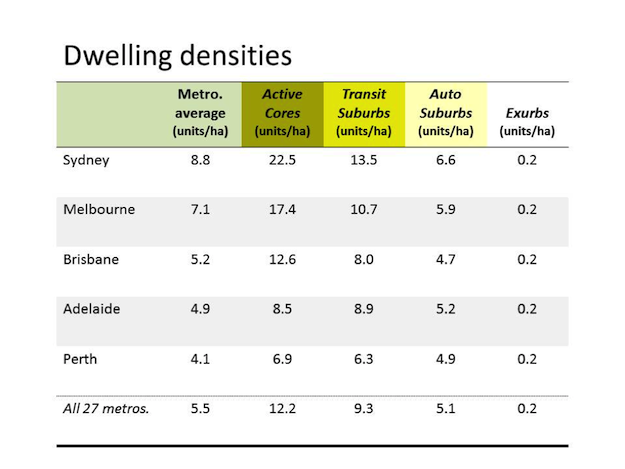

A final chararcteristic of Australian cities is that suburban densities are quite low. Sydney and Melbourne have a few Active Core neighbourhoods with sufficient density to support light rail transit, but the remaing cities and suburbs could barely support a regular bus system, as shown in the table below

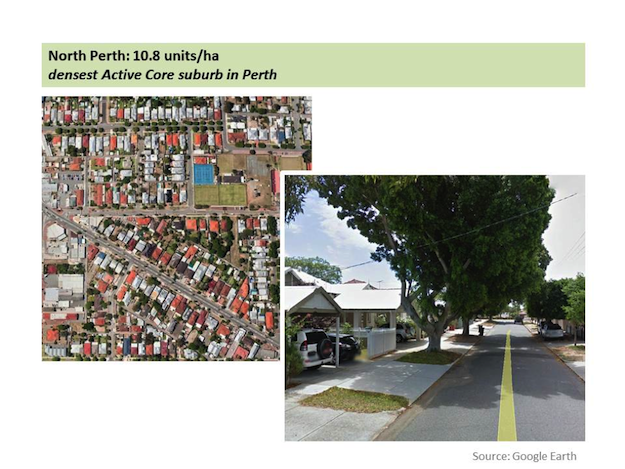

For example, North Perth is the densest Active Core neighbourhood in its metropolitan area, with an average gross density of only 10.8 dwelling units per hectare. Most of the built form in this neighbourhood is comprised of single-story, single-detached homes in the classic bungalow style. Intensification is by adding a second unit in the rear garden.

This national pattern of extensive suburbanization is worthy of further analysis, so this special issue of Built Environment on “Australian Cities in the 21st Century: Suburbs and Beyond” is an aptly named, timely and most welcome addition to the policy discussion. The data leaves no question about whether Australia is a Suburban Nation, but there is plenty of room for debate about what to do about the situation.

Dr. David Gordon is Professor and Director of the School of Urban and Regional Planning in the Department of Geography and Planning at Queen’s University in Canada. He received a doctorate in urban design from the Harvard GSD. Dr. Gordon teaches planning history, community design and urban development and has also taught at Toronto, Ryerson, Riga, Western Australia, Harvard and Pennsylvania, where he was a Fulbright Scholar. David’s most recent books include Town and Crown: An illustrated history of Canada's capital (2015) and Planning Canadian Communities (with Gerald Hodge), which won a 2014 CIP National Award. His latest research compares Canadian and Australian suburbs.

Acknowledgements:

The research in this essay was funded by grants from Western Australia’s Planning and Transportation Research Centre (PATREC) and the Institute for Advanced Study at the University of Western Australia. Co-PIs for the PATREC grant were Dr Paul J. Maginn (UWA), and Prof. Sharon Biermann (UWA). Research assistants were Alistair Sisson, Isabel Huston and Dr Monir Moniruzzaman.

Images:

In text images, provided by David L.A. Gordon, created using Google Maps and Google Earth as attributed and census data from Australia and Canada. Listing Image 'Overlooking Dubbo from the Suburb of West Dubbo (Source: Tim Keegan via Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dubbo#/media/File:Overlooking_Dubbo_from_t...)

References:

Forsyth, Ann (2012) Defining Suburbs, Journal of Planning Literature 27(3): 270-281.

Freestone, R. (2010). Urban nation : Australia’s planning heritage. Collingwood, Vic: CSIRO

Gordon, D. L. A., & Janzen, M. (2013). Suburban Nation? Estimating the Size of Canada’s Suburban Population. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, 30(3), 197–220.

Gordon, D.L.A. & Shirokoff, I. (2014) Suburban Nation? Population Growth in Canadian Suburbs, 2006-2011, Toronto ON: Council for Canadian Urbanism, Working Paper #1. Retrieved from: http://www.canadianurbanism.ca/canu_workingpaper1_suburban_nation/

Gordon, D. L. A., Maginn, P. J. and Biermann, S. (2015) Estimating the Size of Australia’s Suburban Population, PATREC Perspectives. October 2015 http://www.patrec.uwa.edu.au/publications

Newman, Peter and Jeff Kenworthy (2015) The End of Automobile Dependence: How Cities Are Moving Beyond Car-Based Planning. Washington DC: Island Press.

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!