The Hand that Mocked

I am not surprised that the 1960’s drama of Moses v Jacobs, battling it out over the planning of New York City has been made into an opera. The story of local uprisings against wholesale clearance of ‘slums’ is a familiar one, repeated in neighbourhoods the world over from Middleport, to Millers Point and Greenwich Village a classic tale. But Jane Jacobs was more than your average urbanista and took as deep an interest in ‘the city’ as she did in ‘her city’.

Joining the editors of the Built Environment as their ‘books that shaped us’ issue was almost ready for print, I reflected on the difficulty I’d have had in selecting any single one. However, the reflections in The Death & Life of Great American Cities on the uses of the built environment seem to grow more poignant with time, like the sardonic interpretations of the bonded sculptor, which Shelley read in the Egyptian ruins.

Thebes, Egypt, 19th Dynasty, about 1250 BC (Source Babelstone CC BY-SA 3.0)

Observing the micro-details of the everyday, a surreal side of the city emerges that “we all [tacitly] know”. This goes beyond an acquaintance with the particular ordering of American cities or the manners of its middle-classes, which now appear dated, even crass. It is the lucid explanation of the centrality of these ‘lessons learned without being told’ that bring the life of a city into new focus.

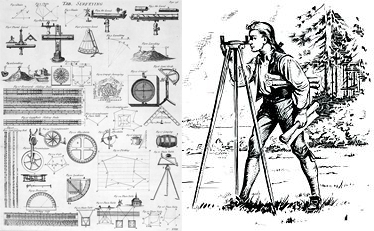

Jacobs shares her curiosity of the meaning of the everyday spaces to ‘ordinary’ social life. She is fascinated for instance with the effects of block sizes. Not something that ever had had much consideration in surveying American property, where metrics were driven by pragmatism. It was Gunter’s arithmetic cunning of merging British tools with the ‘new’ Dutch decimals (with which Ozymandias would have been familiar) and his handy twenty-two yard chain that dictated dimensions, from cricket pitches to Manhattan blocks.

Surveying instruments of Young Washington (Source Anon)

Embedded as she was in her subject, Jacobs could pay close attention to how the shape of place was reflected onto the human interactions within it. This is brought to life in a compelling if absurd picture of people reacting as if bound by space. The boy crying in a tenement for instance whose neighbor, seeing only the abstracted ‘stranger in the lift’, give him scant regard.

To get under the skin of the city, Jacob becomes ‘participant-audience’ of the ballet of social life of Hudson Street. New York put under an analysis where urban form is bound up with subtle social communications, the socio-spatial forces as it were of love, safety, connection and control. This lays bare the complexities and intrigue of the ‘place’ from her own vantage point.

These stories take ‘urban studies’ to a new level of personal engagement, her street, her son, her ‘pipsqueak protest’ are all under the lens. She balances subjectivity with self-awareness, and is frank when she owns the flaws in her description of the local scene saying ‘I have made it more frenetic’. We’re not off the hook either given her constant interrogation of the reader. It’s hardly likely she meant for an audience to simply absorb her wisdom like an unthinking sponge.

What we read is her version of the city as an organism, replete with forces of self-governance and self-destruction. But having spelt out the social consciousness of her own neighborhood may have led to its commodification, an irony not lost in the dark humour of recent South Park episodes. These are peculiarities of the American cities, dealing with the challenges of economic decline and capitalist aspirations.

More fundamentally, Death & Life makes a shift towards bottom-up diagnosis of the state of the city, confronting the “uncomprehending expert” (with their postcode lottery allocation of credit lines or investment) with local experiences and aspirations. The hope is that urbanists might realize that ‘the patient’ might have some insight, especially into whether ‘the cure’ is working.

Not only did this worm’s eye view challenge pseudo-scientific quantification of the nature of urban ‘truth’, it was a call to shared learning. As creators of the life of the city, communities were faced with their role in making, remaking and imbuing the built environment with meaning, and their unique perspective on the health of their own cities. This deceptively simple goal, of connecting local knowledge to decisions, has driven my own research for decades.

As Jacobs puts it in her foreword to the 1993 Modern Library edition, “It is urgent that human beings understand as much as we can about city ecology – starting at any point in city processes.” This work has inspirational breadth, yet for me it is not a treaty but rather a trickle into in a stream of urban self-reflection from all manner of urbanists, co-authors of living cities.

As ever if you have any views to share on this subject, we encourage you to consider using DISQUS for comments (see below), writing a reponse blog for the Built Environment or just tweeting @Blogged_Env!