The Power of Plans

Our aim here is to explore plans which worked, plans which led to positive achievements and plans which were judged to be successful. It is a theme too often neglected, in favour of the critique of error and the exposure of failure. Yet we can surely learn the

lessons of success as readily as the lessons of failure.

It is not our objective to argue for any particular outcome, nor to establish an ideal form. It is to bring into focus the power of plans as schemes for spatial ordering. We acknowledge the importance of studying how powers are wielded, the nature of regulatory controls, and the relative powers of diverse actors. But we contend that the potential for plans to create change deserves scrutiny and – given the enormity of present challenges – perhaps now more than ever.

The notion of success in planning will always be a slippery concept. As Olsen reminds us in his history of town planning in London:

A town plan cannot be judged a success until it has shown the ability to adapt itself to changing circumstances, changing technological and functional requirements, changing aesthetic values, changing kinds of life desired by its inhabitants. (Olsen, 1979)

Olsen’s tall order arises from the sheer longevity of plans. Time matters: projects which flow from big plans have a long-term impact and long-term shelf life. The British are still using the alignments of parts of Roman roads. We know that the context for judging plans can shift over time, not least as cultural values change. Plans for London’s urban motorways developed in the 1960s were seen as the essence of modernism and enjoyed widespread popular and political support. The plans failed partly because their demand forecasts were inadequate and partly because changes in policy made public transport a more acceptable mode for investment. But the major reason for their failure was almost certainly a widespread change in public values.

When the motorway plans were fi rst considered in the early 1960s both main political parties and a wide spectrum of public opinion were strongly in favour. When they were abandoned in 1973 there was hardly any support. Hall concluded that there was simply ‘a profound shift of mood amongst thinking people in London and other cities about the problem and about its solution’ (Hall, 1980 p. 85).

Planning in Retreat

In looking for achievement we are on a slippery slope, easily caught in the crossfire of politics, social values, and sheer nihilism. Why bother to plan at all? Why not leave decisions to the market? In Britain belief in planning is widely seen to be at a low ebb, in a poorer state than it has been since 1947, with planners regarded as mere licensees for developers rather than creators of better places. Visions are conspicuous by their absence, according to a former Chief Planning Inspector for England (quoted in Stafford, 2022). The local planning system is grinding to a halt, morale is low in council planning departments. An open invitation to council planners to submit evidence of their problems anonymously online was described as a howl of despair, portraying a system on the edge, manned by staff crushed by overwork, and suffering regular abuse from the public and even their own councillors (ibid.).

Concluding his comparison of British planning with best practice in the rest of Europe, Hall reached similarly gloomy conclusions. In 1967, a peak year for housing completions in the UK, planners were at work on regional plans throughout the country, new towns were commencing at Warrington, Peterborough, Telford and Milton Keynes, and government employed large numbers of professional planners. That last wave of new towns proved to be remarkable economic success stories. All told it was the zenith for a technical, technocratic, but fundamentally benign planning. Afterwards, Hall argues, planners went downhill in terms of skills, competence, and self-belief:

Planning and planners have been residualized into a purely passive role… It is not that we lack the powers: it is that we have lost the will, and with it the energy and the competence that once made British planning the envy of the world. (Hall, 2014, p. 306)

The British General Election of 1945 had brought Labour to power and confirmed the strength of a planned vision for the future. Labour’s Manifesto had no reservations: ‘We stand for order, for positive constructive progress… Labour will plan from the ground up’ (quoted in Matless, 1998, p. 200). This collapse in vision and belief was seen in Britain as much as in the USA (Wray, 2019). But what had caused it?

The answer lay in the rise of a new political philosophy, a new political order, which disavowed the role of the state in regulating, helping to underpin, and shaping the direction of society, even in the light touch approach seen in post-war Keynesian economics. The new political order wanted deregulation, a small state, and the economics of laissez faire. It was rooted in the Chicago School economics of Hayek, Von Mises and Friedman, and came to be known as Neoliberalism. Elegantly dissected in Gary Gerstle’s brilliant political history The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, we can trace its origins in academia, in the support offered by right wing politicians and business lobbies in the 1970s and onward, in the rise of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, and in its eventual morphing into the politics of the US Democratic President Bill Clinton and Britain’s New Labour Prime Minister, Tony Blair. Neoliberal economics helped to deliver huge inequalities, political and social division, an acute financial crisis in 2008, and the subsequent political backlash which brought Donald Trump to power (Gerstle, 2022).

But more than this, Neoliberalism denied the power and indeed the authority of government to shape the future. While deregulation was at Neoliberalism’s heart, both Hayek and Friedman were openly scornful of the ability of government and its plans to achieve any good, while believing fervently in social progress through technical innovations. In effect, they conflated planning with centralized, command-control state interventions, and gave planning a narrow definition. Despite plentiful empirical evidence to the contrary (Wray, 2019) planning, both in its regulatory and visionary guises, was caught in the political cross wires.

In Defence of the Capable State

As, respectively, former editor and political editor of The Economist, John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge were scourges of the big state and proponents of globalization and laissez faire. They would have been comfortable with Hayek’s belief that ‘planning leads to dictatorship’ (Hayek, 1944, p. 78) and his view that we only need to create the conditions for progress, not to plan for it – a position readily supported by Milton Friedman (Friedman and Friedman, 1980), and the influential right wing ideologue Ayn Rand (Burns, 2009). Oddly, Hayek’s distaste for technocratic plans found its echo in the thinking of the brilliant libertarian writer Jane Jacobs, who offered a paradigm shifting view of what, and who, plans might include.

The opening words of her celebrated book The Death and Life of Great American Cities are simply: ‘This book is an attack on current city planning’ (Jacobs, 1961).

The COVID-19 pandemic woke Micklethwait and Wooldridge to the importance and power of the state, realizing that effective government strategy and action is often essential. In their view, while Eastern states have respected their bureaucrats and paid them accordingly, the Western state has been allowed to atrophy (Micklethwait and Wooldridge, 2020). Governments who handled COVID-19 well took government seriously and modernized their states. Governments who handled it badly (including the UK and the USA) had embraced the minimum state model and a deregulated, anti-planning agenda. It is a model which amplifies existing inequalities, leaving ‘Swiss Cheese’ coverage. Charity and voluntary sectors can provide supporting networks: they cannot substitute for effective governance capacity and legitimacy. With reactive interventions, and without strategic priorities or common goals (Natarajan and Cho, 2022), the UK government lacked COVID-19 allies (Natarajan, 2021), and the worst off had to rely on underfunded non-governmental organizations for essential supplies (Cho et al., 2021).

Bent Flyvbjerg, the economist and prominent critic of mega projects, has been adjusting his view on big plans. His classic book Mega Projects and Risk showed how things went wrong: how, according to Flyvbjerg, project promoters systematically misinform parliaments, the public and the media, resulting in hugely risky and expensive projects (Flyvbjerg et al., 2003). His new paper ‘Make Megaprojects more Modular’ takes a refreshingly positive tone (Flyvbjerg, 2021). Big plans can work if they have a modular structure and can be scaled up from interchangeable components – something which the British motorway builders in the 1960s were well aware of (Wray, 2016). But you still need that overarching long-term plan.

Gerstle provides a startling example of the need for sound plans (Gerstle, op. cit.). Even Neoliberals recognized the role of the state in projecting military power. The US campaign in the Iraq War began with an air attack, involving 20,000 missiles fi red at Iraqi targets. An overland assault saw 170,000 motorized troops moving in from bases in adjoining countries. Saddam Hussein’s army offered little resistance and US forces took Baghdad within days. In the words of a banner hung on a US aircraft carrier, where President Bush landed to mark his triumph, the message was ‘Mission Accomplished’.

Except that it was not. The mission had hardly begun. For military success had to be followed by the long hard slog of building a trusted new government and rebuilding a war-torn country. Iraq’s infrastructure was shattered, electricity and water systems worked only intermittently, the oil refineries were near collapse, the phone system destroyed. In election debates with Al Gore in 2000 Bush had been sceptical about nation building, seeing it as distraction for the US Army: government reconstruction never worked and was a task best left to the private sector. America had of course accomplished social and economic reconstruction in Germany and Japan after World War Two – and reconstruction plans for post-invasion Iraq had been drawn up in the US State Department. But the plans remained under lock and key. Government sponsored reconstruction was a thing of the past and a liberated Iraq could be left to market forces. The world knows how that story ended – and should heed the long painful road to urban recovery (Saeed et al., 2022; Quadri, 2022).

Gerstle concludes that Neoliberalism has run its course, its relevance fading rapidly. Larry Kramer agrees, arguing that Milton Friedman did not secure a perfect and timeless wisdom: ‘However well suited it may have been to addressing stagflation in the 1970’s Neoliberal policy has fostered grotesque inequality, fuelled the rise of populist demagogues, exacerbated racial disparities and hamstrung our ability to deal with crises’ (Kramer, 2022).

It is evident that we need more intelligent government, more trusted government, but how do we get it? Surely one starting point must be better plans – and, if so, it follows that we need to start looking carefully at the power of plans, at plans that have worked, and at planning achievements, asking how and why they worked. It means returning to the spirit of planning which prevailed before what the US politician Newt Gingrich described as the Crucible of ‘68: ‘If you go back to 1967 you’d find a generalized broad optimism which disappeared sometime during the crucible of ‘68 and from which we have not to this day fully recovered’ (quoted in Zaretsky, 2012, p. 143).

Learning from the Case Studies

To cast light on our theme we commissioned papers internationally, with a relatively open brief that avoided closing down the meaning of achievement. Our concern was to hear accounts from the coalface, with a range of insights on the strategic public interest issues currently addressed by plans, including:

- Landscape protection;

- Nature conservation and biodiversity;

- Transport and city region building strategy;

- Urban extension and growth;

- Regional development and the organization of civil society;

- City decline, shrinkage, and regeneration;

- Landed interests and economic plans,

- Climate change and ‘non planning’.

Liverpool

Liverpool had ambitious visions in the 1960s, rooted in the ideas of Le Corbusier and the urban motorway builders (Liverpool City Council, 1967). The urban motorways were unrealized and the high-rise housing proved a signal failure – the irony being that economic decline and failed plans sent the city centre to sleep for nearly twenty-five years, securing the retention of its historic core.

In the early 1980s Michael Parkinson had doubted Liverpool’s ability to solve its problems, reflecting a mood of despair and disappointment, fuelled as much by the failure of the 1960s plans as by the city’s evident economic collapse. Hall’s review of economic changes in British cities in the 1970s painted a grim picture (Hall, 1989). Between 1971 and 1981 Liverpool lost 79,000 jobs in manufacturing and logistics (a third of the total), generating only 12,900 new jobs in knowledge-based services (ibid.). It was the worst performing provincial city, widely viewed as a basket case.

Though much remains to be done, Liverpool has been slowly turned round by a succession of area-based plans, plans which have been achievable and relatively modest (Parkinson, 2022). The city’s population is growing. There has been significant private sector investment, especially in the city centre. Almost without exception these plans and investment projects have been led and funded by agencies external to the city council, providing both strategic direction and resources: by central government’s Merseyside Development Corporation for the disused south docks and waterfront; by the EU, which made available huge funds over a long timescale; by the Blair government’s North West Regional Development Agency, which supported the Liverpool Vision plans for the city centre and first identified the potential of a ‘Knowledge Quarter’ around the University; and by Grosvenor, the investor/ developer behind the huge Liverpool One project. Realistic plans and visions were essential, but so too were stable platforms beyond the city council, whose leadership had sometimes been turbulent.

Perhaps the essential unifying vision for the 1980s and beyond came from the former Merseyside County Council, a city region structure abolished by Margaret Thatcher’s government. The County’s planners had found nearly 3,400 hectares of derelict and unused land. Turning their back on dispersal and new towns their structure plan’s ‘urban regeneration strategy’ proposed to ‘concentrate investment within the urban county and especially on those areas with the most acute problems, enhancing the environment and encouraging expansion on derelict and disused sites. It would restrict development on the edge of the built-up area to a minimum’ (Merseyside County Council, 1975). It was probably the first UK plan to advance this influential ‘urban regeneration’ concept. City region governance has now returned to Liverpool, with a new Combined Authority and Metropolitan Mayor. Perhaps the renewed arrangements will prove equally effective.

Liverpool: with its place-based initiatives this is ‘a clear example of the decisive role the public sector can have in incentivizing, rewarding, or de-risking market sector involvement’. (Parkinson, 2022, p. 496)

New York

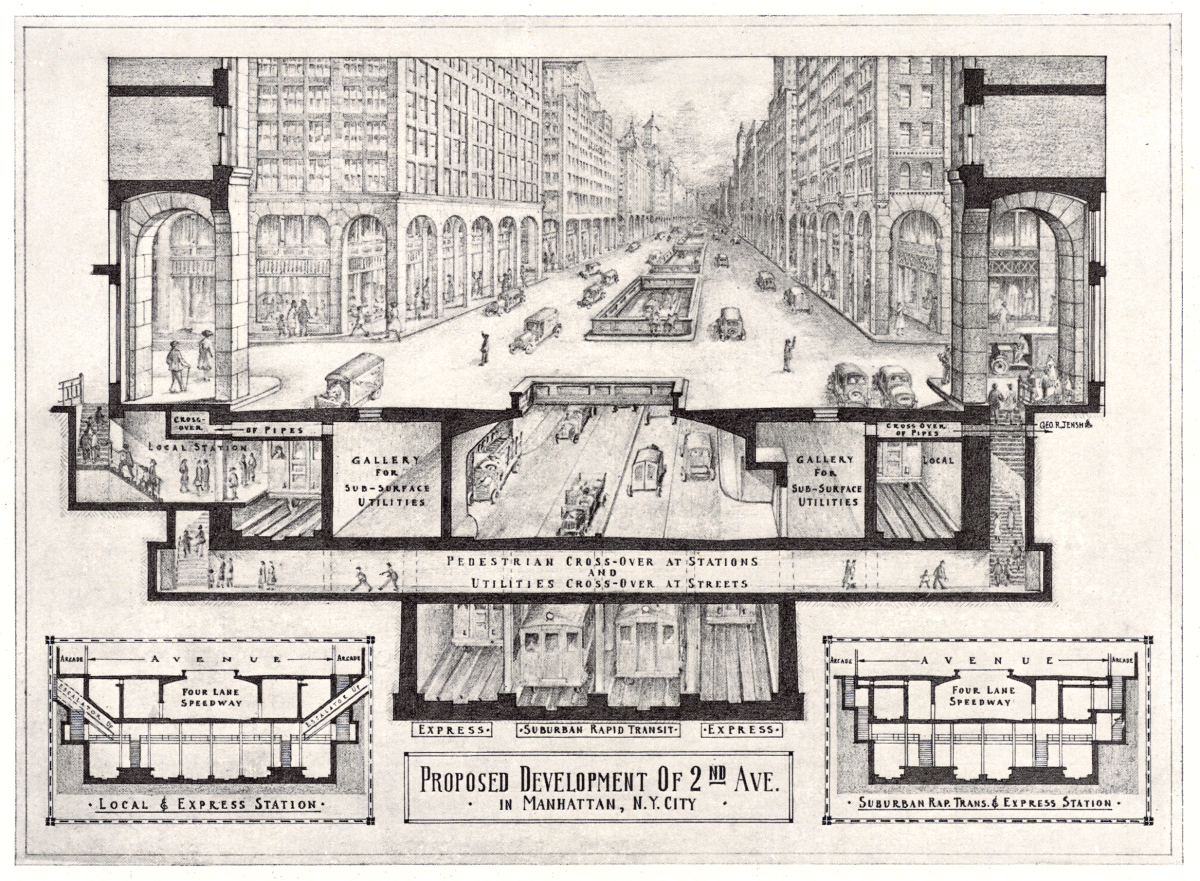

New York, like Liverpool, is a city which has experienced rapid growth and rapid decline – and an economic turnaround more impressive than Liverpool. But there the comparison ends. New York is rich and powerful and, as Bob Yaro (one of its most prominent planners) explains, has long been planned on a city region scale. The origin of its series of great plans lies in a small number of planning pioneers and philanthropists (Yaro, 2022).

As Yaro explains, New York’s Regional Plan Association (RPA) goes back to 1922 when the Committee on the Regional Plan for New York and Its Environs was established by the Russell Sage Foundation. RPA was incorporated as a permanent, independent, non-governmental, and not-for-profit organization in 1929. Over the past century, a significant proportion of RPA recommendations have been implemented.

RPA’s first great plan in 1929 included proposals for a network of limited access highways, bridges, tunnels, railroads, and public open spaces. Much of this plan was implemented, especially the road proposals, through the eff orts of the autocratic bureaucrat Robert Moses, seen as a hero in the 1930s, but a villain by the 1960s. Times had changed and with them social values – and plans which had once seemed visionary became an object of scorn. As Yaro reminds us, there was always more to the RPA plans than roads and indeed later iterations came to place increasing emphasis on public transport investment and strategic greenspace (one of Moses’s lesser known achievements).

In addition to producing and reviewing strategic plans for New York, RPA became critical to implementation, campaigning for specific projects, often successfully and over long timescales. Its strength lay in its consistent long-term thinking, independence (assured by philanthropic funding) and in the quality of its research, its staffers and board members, sometimes former professional planners with great experience. RPA became expert in strategic advocacy, mediation, and negotiation. As a former RPA President put it, ‘RPA’s job is to advance ideas whose time has not yet come… It’s often difficult for politicians and bureaucrats to take positions on controversial issues or to lead on these issues, but RPA can make it safe for them to do so by getting out in front’. RPA remains well suited to an individualistic free market society with commitment to philanthropic funding to secure agreed public ends.

New York: the region has benefitted greatly from an independent and bold civil society organisation, the RPA who gets out in front ‘to advance ideas whose time has not yet come’. (Yaro, 2022, p. 520)

Dublin

The 1960s and 1970s were not successful decades for planning Dublin. Like other cities, Dublin bought into outer urban extension with car dependent suburbs, little investment in public transport and large-scale road building (including some damaging urban highway proposals). Those urban road schemes came in for vocal opposition.

There followed a long and sometimes hesitant process towards a more balanced and effective transport plan. A starting point came from the transport body Córas Iompair Éireann (CIÉ). In 1972, its General Manager had seen the plans for a light rail system for Tyneside. Could Dublin have a similar system? The Dublin Rail Rapid Transit Study was published by CIÉ in 1975, the preferred scheme being a 71 km electrified suburban rail system. But economic retrenchment meant that the ambitious plans were not implemented. Car traffic was up and bus use falling. The recommendations were abandoned.

As in Liverpool, the arrival of European Structural Funds encouraged a more strategic approach to investment with an emphasis on programmes rather than projects. A proposed transportation study was commissioned to secure this more structured approach, giving an objective rationale for European investment. It would need to: provide a coherent policy for investment in the Dublin transport system; make the case for European Structural Funds financial assistance; and overcome a public policy vision which had favoured the private car over public transport.

The new approach worked. Phase One of the study was completed in December 1991. It identified the need for a transportation planning process rather than another one-off study. A spirit of openness ran through the study, including public consultation and a series of in-depth interviews with opinion formers. Phase Two had a governance structure designed to achieve the maximum level of buy-in across the public sector, business and civil society.

In the main the study outputs were a long-term strategy, a shorter-term delivery plan, and a process for strategy review and development. It was a turning point, the achievements being:

- The significant change in approach was accepted;

- The plan became a process;

- The institutional structures were reformed and strengthened;

- The need for sustained investment was accepted and acted upon.

Substantial improvements have been delivered. A 42.5 km light rail system was developed on a phased basis and it carried 48.3 million passengers in 2019. The electric and suburban diesel rail network was extended, the suburban rail fleet was renewed, and new stations were opened. Smartcard integrated ticketing and an integrated fares structure are in place. Public transport journeys rose sharply. In their paper, Mangan, Steer and Chadwick (2022) argue that a new policy window had opened, with broad acceptance of the problems, their nature – and the interventions needed to address them.

Dublin: a platform on transport whose ‘open and inclusive process brought together policy communities’, and enabled learning from past mistakes together. (Mangan et al., 2022, p. 541)

Adamstown

Adamstown is a major urban expansion area located west of Dublin City Centre, in the local authority area of South Dublin County Council (SDCC). It was expected to be constructed over a fifteen-year period, not repeating the mistakes of past major housing investment in the Irish State, creating a desirable place to live. The masterplan promoted a shift away from the traditional suburban housing estate format towards more sustainable and compact form development. The County Council did not make an explicit statement of vision. Nevertheless, there was clarity of purpose in spatial planning and place making. The Adamstown Planning Scheme was seen as a great success, with awards from the Irish Planning Institute, the European Council of Spatial Planners, and the Royal Town Planning Institute.

The Adamstown Planning Scheme was approved by An Bord Pleanála in 2003, in the midst of a booming house market. It was to be a private sector led development, guided by the Council’s land-use, design and infrastructure requirements, as set out in the Scheme. Following the Irish property crash in 2008/2009 the private sector only model had to be rethought: 100 per cent reliance on private sector investment was not going to work. State intervention was needed, beyond the creation of a planning framework. In 2020, €15million was allocated by the State through the Local Infrastructure Housing Activation Fund.

The Council matched the funding with a further €5million and in 2021 was awarded €9.7million under the Urban Regeneration Development Fund. Jackson and Basford (2022) lay great emphasis on the need for vision. But it is evident that an institutional framework is equally important, and one which sits comfortably with prevailing circumstances and needs. The need for public investment and involvement was a missing element. The economic buoyancy of the early years disguised the need to ensure long-term stability underwritten by the State. This view is reflected in the National Economic and Social Development Office 2019 case study, where Adamstown is noted as a cautionary tale, explaining that the programme did not have all elements necessary. While Adamstown had vision, it lacked the necessary institutional and funding framework and as a purely market led development, it was severely affected by the economic downturn.

Adamstown: despite ongoing delivery challenges, the consistency of vision means that ‘the parts of Adamstown which have been delivered present exemplars of high quality place-making’. (Jackson and Basford, 2022, p. 561)

Parc de la Deûle, Lille

Landscape is commonly inserted into wider developments: shopping centres are landscaped; new towns are landscaped; motorways and high-speed rail lines are landscaped. But creating a better landscape is much less often regarded as an end in itself. Capability Brown created new landscapes for his aristocratic clients throughout Britain. In New York State, Robert Moses created millions of acres of new regional parks (Wray, 2019, p. 149). But these are important exceptions. It would be difficult to imagine plans for a new landscape securing approval through any system of cost benefit evaluation.

The creation of the Parc de la Deûle in the metropolitan area of Lille is therefore an ambitious plan. Bouche Florin (2022) contends that the inspiration and high-level vision for the park came from the Council of Europe Landscape Convention, an international treaty which encourages public agencies to protect, manage, and plan landscapes throughout Europe. He argues that the convention has given legal value to these polices and puts interrelationships between humans and nature at the heart of the discourse, whilst the decline of French regional planning has done much to undermine the ability to create new landscapes.

The Parc de la Deûle was the winner of a Council of Europe award for landscape creation. Located south of the city of Lille along the Deûle river, despite the inheritance of wetlands, much of the landscape was blighted and degraded by the industrial revolution. The Deûle had become heavily polluted by noxious industries, and there was much wasteland, dumping, and abandonment. During the 1960s plans first began to regulate development. In 1973 a specific landscape mission was created and later enshrined in a landscape office within the ministry responsible for regional planning. But the impetus for action came from the poor quality of Lille’s drinking water supplies, alongside the desire to create green links between urban areas and countryside areas which were largely inaccessible for recreation.

The inter-ministerial committee on regional action and planning encouraged and supported the new park, with the state purchase of 110 hectares of land. The Artois-Picardy Basin agency, responsible for the management of water resources purchased an additional 500 hectares, but little was achieved until 1992 when a body was created to implement a master plan for Lille and its environs. Again, the main objective was improved drinking water. In 2002 Lille Metropole Communauté Urbaine became responsible for natural areas around the city giving management to a ‘mixed syndicate’. The ambition is the creation of 10,000 hectares of accessible green space – 400 hectares has so far been achieved in a variety of initial landscape projects in the Deûle Valley. The vision for landscape creation is certainly well expressed. But without a clear, stable driving force, and funding over long timescales for acquisition, implementation, and management, it is not clear how quickly the vision will be turned into reality.

Parc de la Deûle: a result of the European Convention, which ’adds weight to calls for intervention by public authorities to protect, manage, and plan landscapes for all’. (Bouche Florin, 2022, p. 574)

Shenzhen

In their increasingly determined search for economic growth, the UK government – and many leading UK commentators – have turned their gaze on the planning system: if only we could have a simpler system, with less scope for objectors, which carries forward Mrs Thatcher’s experiments in laissez faire and does away with red tape. Thus, the new policy initiative is for ‘free ports’ with low tax, high deregulation, and little planning.

Shenzhen could not be a more topical case study. It was China’s first Special Economic Zone, has seen phenomenal economic growth and development, and is currently emerging as China’s low-carbon ‘Silicon Valley’. Throughout the process, strategic spatial planning has been seen as a powerful tool for development and change, catapulting a small agrarian border town with only 330,000 inhabitants into a new role as a global economic dynamo. The process started in 1980 when a team of 100 experts were sent to the Shenzhen to revise its growth plan, creating a window for domestic and external investment. Power was delegated to local authorities to build a 327 km long multi-centre linear city. Land was initially given out free of charge to attract investment and later sold at low prices.

Thus, a rudimentary land market began to develop in a socialist economy. Different ‘zone builders’ were allocated sites, whilst green corridors were protected. The city government borrowed to provide necessary infrastructure, while the 1986 plan laid out the framework for a transport network. The aim was popularly seen as creating ‘Hong Kong’s efficiency and Singapore’s environment’. Green corridors were created to allow for tree planting and cycle lanes. Alongside the big plans local farmers were allowed to retain and develop land, and these became ‘urban villages’ with non consented medium-rise buildings to house migrant workers.

A revised master plan was drawn up in 1996. Instead of focusing purely on economic growth the plan required conservation of agricultural land and ecologically sensitive systems. Post 2000 there has been a further shift towards plans for a ‘smart and sustainable city’. A new planning study, Shenzhen 2030, was a strategic cross sectoral document, going beyond spatial issues to consider social disparities and housing, including the improvement of the ‘urban villages’. The 2010–2029 master plan refl ected these wider concerns, dividing the city into four zones: no go areas with high agricultural and conservation value; restricted development areas; developed or built-up areas; and areas suitable for development. Alongside were policies to protect natural and cultural heritage, green spaces and water areas. There were extensive public consultation exercises in developing the plan, which is a legal document to be implemented by various government agencies.

This is top-down technocratic planning. It has done exactly what the Chinese government hoped for: delivered very high levels of investment and economic growth. As time has gone by the planners have become more alert to the other dimensions of balanced development. Ng (2022) concludes that ‘the successful story of Shenzhen’s strategic spatial planning is a result of multi-scalar efforts and a political will to overcome constraints to achieve top-down assignments’. This is not economic growth induced by deregulation and the abandonment of plans; it is planning for growth, with clear vision and powerful mechanisms for implementation, which fits China’s essentially authoritarian governing culture.

Shenzhen development of the megacity is ‘the result of multi-scalar eff orts and a political will to overcome constraints to achieve top-down assignments’. (Ng, 2022, p. 590)

East Kolkata Wetland

The final case study, Kolkata, Bengal, India breaks our own rules. This is not the happy story of an apparently successful plan but rather its antithesis: a suite of complex planning problems which to date has eluded solutions.

Kolkata was once the capital of India, ruled by its British colonialists. Since Independence, and following India’s recent rapid growth it has become a dynamic city, the third largest in the country. Adjoining the city, which is sited on low lying land near the River Howrah, is the East Kolkata Wetland, covering some 12,500 hectares of wetlands, designated as an international site for nature conservation under the provisions of the Ramsar Convention. This might seem to off er a straightforward objective: zone for nature conservation, stop development and prepare a nature conservation management plan.

But things are not so simple, as the East Kolkata Wetland already has extensive uses other than nature conservation and different interests are at work. The British colonial rulers had hoped to deal with the problems of sewage disposal for the city by building sewage treatment plants to the west. But that plan was not implemented, so instead Kolkata’s sewerage flows into the wetlands through a network of canals, lock gates and sluices. As it happens the East Kolkata Wetland does an effective job in filtering the water as a sort of giant ‘sustainable urban drainage scheme’, naturally processing Kolkata’s daily output of 750 million litres of wastewater. It also effectively absorbs excess monsoon rainfall. Thus, we have potentially competing uses for the wetlands: sewage treatment, storm overflow storage, and nature conservation. There are others. Historically there was a significant leather tanning industry on the edge of the wetlands, disposing of its effluent by the easiest route. Leather tanning is not the cleanest of activities and the industry is still there, alongside other economic activities: waste disposal and segregation of garbage; and sewage treatment through fi shing and farming. The latter provide significant employment for poorer members of the community. Part of the East Kolkata Wetland has historically been used for solid waste disposal.

The wetlands also off er visual amenity and cleaner air, and an escape from the city. This potential has been spotted by residential property developers, particularly as a site for tower blocks. Local government and developer interests have contested the nature conservation and protection. There is obviously potential for outdoor recreation and green space. What we have here is essentially a complex and largely unplanned system.

Mukhopadhyay (2022) contends that the ‘lack of regulations has left a gap in planning, with no systematic means to shape let alone permit the development in the vicinity of the EKW [East Kolkata Wetland]’. She maintains that the wetlands require stronger statutory protection at sub-state level and more awareness of local stake-holder involvement. The powers of the existing regional body to restrict development are limited and the primary local government intervention is (weak) control of sewage disposal levels. Governance of the East Kolkata Wetland is multi-level with central, regional, and local components.

East Kolkata Wetland is a stark contrast with the determined planning style seen in Shenzhen . It is a somewhat chaotic muddle, lacking both agreed vision and a focus for decisions and implementation. One can develop without environmental planning, but the results are not appealing and, as climatic change continues, the downsides are likely to become more apparent.

Kolkata: given the critical social, economic and ecological development processes supported, ‘strong planning is needed to preserve the wetland and establish its relation to the city’. (Mukhophayay, 2022, p. 600)

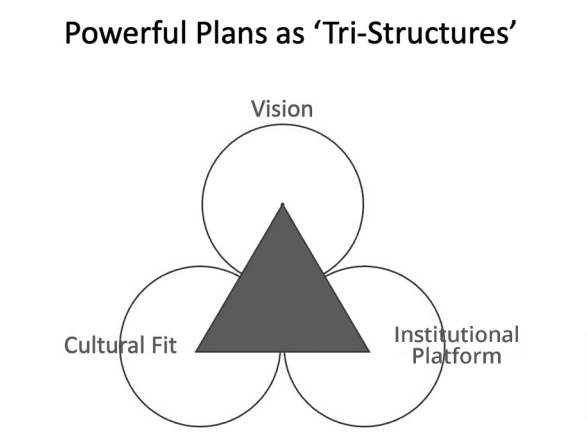

Powerful Plans as Tri-Structures

Drawing on our case studies we can identify three central factors in plans which succeed – a triform or tri-structure. The first and most critical component is vision. The second is a sound institutional platform. The final element in the tri-structure is cultural fi t. Once all three elements are in place, we have the underpinnings for a robust and powerful plan. Vision is referred to explicitly in the first six papers, and in the final piece it is implicated in notions of an area for ‘wise-use’ of water. What is vision and where has this increasingly important planning concept emerged from? A student educated in a planning school some fifty years ago (like one of the authors) could have gone through their studies without understanding vision. They would have heard a great deal about forecasting, demographics, goals, objectives, sociology, economics, and cost benefit analysis – but scarcely a whisper about vision. Look at the indexes of some seminal texts on planning history like Lewis Mumford’s The City in History (1961), Peter Hall’s Urban and Regional Planning (1974) and Stephen Ward’s Planning and Urban Change (1994). There are no references to vision. But vision does appear (and figures prominently) in Henry Mintz berg’s corporate planning classic The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning (1994).

The idea of vision appears to have originated in management and corporate thinking in the private sector and found its way across to planning by process of osmosis. One potential reason for this, as a planning consultant put it to us, is that times have changed. Until the late 1960s planning was essentially a public sector led process. Visions were all embracing and came from a small number of highly influential paternalistic luminaries – such as Patrick Geddes, Ebenezer Howard, Frank Lloyd Wright, Robert Moses, Le Corbusier. The 1960s plans sometimes referred to by our contributors were rooted in their ways of thinking. Peter Hall recalled that during the planning process for the new city of Milton Keynes: ‘Mel [Webber] came over on a sabbatical to London and in momentous seminars convened by Richard Llewellyn Davies we sketched out the basic concept for Milton Keynes’ (Hall, 2014, p. 272). This was essentially a visionary (albeit elitist) process, though one might choose to argue that the technocratic result was benign (Wray, 2016).

Today planning in Britain is as much private sector as public sector activity: almost half Royal Town Planning Institute members work in the private sector (RTPI, 2019). As our consultant suggested, planners need to sell their ideas to backers, often to funders and bankers, and need a compelling vision and narrative for each project. Without a vision there is no focus for contesting goals, debate on strategic priorities is scattered, and local civil society is left to carry the can for the worst off (Cho et al., 2021). In short, as society has become individualistic, atomistic, and pluralistic, plans have reflected that change.

Plans have power in shaping direction and that is what vision evidently supplies. Perhaps it is helpful to see vision as an early stage in the process of creative thinking, outlined by Professor Keith Sawyer, an expert on the psychology of creativity. Sawyer suggests an eight-stage creative process. Stage One involves finding and formulating the problem in such a way that it will lead to creative solutions. Later stages gather information, generate alternative ideas, and combine them in various ways, developing and transforming the ideas as they are expressed in the external world (Sawyer, 2012). A number of our contributors talk about visions in this way, even if they do not use the terminology. Visions are indeed about finding the problem, as Mangan, Chadwick and Steer (2022) explain.

Alongside vision, and of critical importance if plans are to be turned into reality, comes the imperative for an institutional platform. It can be supplied in various forms, coming from the private sector alone, from developers or landowners, from government, from government agencies, or even from supra national agencies like the EU (Wray, 2016). Government and EU platforms were critical to delivery in Liverpool, and in Dublin. In New York a powerful role was taken by an independent not-for-profit institution out with government. Institutional platforms need resilience and of course they need longevity if they are to supply long-term direction, funding, and keep the vision alive. A great vision will go nowhere without a strong institution behind it. There was high-level vision in Parc de la Deûle, yet a sequence of relatively weak institutional platforms. When things went wrong with delivery after the 2008 Irish housing market crash, Jackson and Basford (2022) explained how the institutional platform had to be modified to include strong state support. Kolkata’s vision was blurred, just as its platform was shaky.

Next, and closely connected with the institutional platform, comes cultural fit. In New York, individualism and free market orientation called for a body beyond the public sector. In Dublin, the role of the state and of the EU was readily accepted, so long as there was wide consultation with civic society. In China a top-down model was applied, reflecting a more autocratic and centrally directed society. The top-down model worked in China and might have worked in Britain or the USA in the 1940s. It would not work in Britain today – nor indeed in Kolkata. The UK government’s recent attempt to impose housing requirements on local authority plans by means of an algorithm was met with strong protest from all sides (Wray, 2020) – and swiftly withdrawn.

It is apparent that the processes involved in shaping visions have a close relationship with cultural fit. Thus, in more centralized or authoritarian societies – such as China, especially in the early stages of planning for Shenzhen – vision was created by technocratic elites and imposed without consultation. In societies with a strong bias to market solutions – such as the USA – technocratic and business elites played an important role in shaping visions. In both cases, with the passing of time a tilt towards consultation with wider buy-in to visions emerged, as was also the case in Dublin. In Liverpool vision building became a shared task for the council, for government agencies, and for the EU. In Kolkata, as we noted, vision was blurred by the number of interest groups and the weakness of any cohesive institutional platform – thus, a form of ‘non-plan’ has prevailed.

When vision, institutional platforms, and cultural fi t come together effectively, a powerful and successful plan will emerge. If an element is missing the tri-structure does not function. But there is a final dimension which we first identified at the outset: time. As time passes new ideas and events emerge, old ideologies are questioned, a new generation rises to power. Time can erode vision, weaken platforms, and change cultural fit, sometimes quite dramatically. We can see this at work in many of the case studies. At a much higher level Gerstle (2022) explains how the New Deal Order, as he puts it, was displaced by the Neoliberal Order and how the Neoliberal Order, which has done so much to undermine the case for plans and the capability of planning institutions, may itself be coming to an end. Change is being driven as much by new populist leadership as by the need for capable governance to tackle problems on the horizon, from pandemic to climate change, to inequality, to energy crisis (Wray, 2020). And in any event, as Olsen (1979) reminded us in the opening words of this paper, time is the ultimate judge of planning success.

REFERENCES

- Bouche Florin, L.-E. (2022) Implementing the Council of Europe Landscape Convention: The Deûle Park, reawakening of a landscape. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 566–580.

- Burns, J. (2009) Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cho, H., Ilie, E. and Natarajan, L. (2021) A Civil Society Perspective on Inequalities: The COVID-19 Revision. UK2070 Working Papers, Sheffield University. Available at: http://uk2070.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/UK2070PapersSeries3.pdf.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2021) Make megaprojects more modular. Harvard Business Review, November/ December. Available at: https://hbr.org/2021/11/make-megaprojects-more-modular.

- Flyvbjerg, B., Bruzelius, N. and Rothengatt er, W. (2003) Mega Projects and Risk. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Friedman, M. and Friedman, R. (1980) Free to Choose. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovitch.

- Gerstle, G. (2022) The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hall, P. (1974) Urban and Regional Planning. London: Penguin.

- Hall, P. (1980) Great Planning Disasters. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Hall, P. (1989) London 2001. London: Unwin Hyman.

- Hall, P. (2014) Apologia pro vita sua, in TewdwrJones, M., Phelps, N.A. and Freestone, R. (eds.) The Planning Imagination: Peter Hall and the Study of Urban and Regional Planning. London: Routledge.

- Hall, P. (2014) Good Cities, Better Lives. London: Routledge.

- Hayek, F. (1944) The Road to Serfdom. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Jackson, R. and Basford, L. (2022) Authentic visions and effective plans: The Adamstown Strategic Planning Zone (SPZ) in the Republic of Ireland. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 548–565.

- Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Kramer. L. (2022) The market is not an end in itself. Financial Times, 16 September

- Liverpool City Council (1967) Liverpool Builds 1945–1965. Liverpool: Liverpool City Council.

- Mangan, P., Steer, J. and Chadwick, N. (2022) The importance of process in planning: the Dublin Transportation Initiative. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 528–547.

- Matless, D. (1998) Landscape and Englishness. London: Reaktion.

- Merseyside County Council (1975) Merseyside Structure Plan: Stage One Report. Liverpool: Merseyside County Council.

- Micklethwait, J. and Wooldridge, A (2020) The Wake Up Call. London: Short Books.

- Mintzberg, H. (1994) The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. Englewood Cliff s, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Mukhopadhyay, C. (2022) Climate change adaptation and built environment resilience: East Kolkata Wetland strategies. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 594–612.

- Mumford, L. (1961) The City in History. London: Secker and Warburg.

- Natarajan, L. (2021) Policy-making for an ‘unruly’ public? Cities and Health, 5(sup1), pp. S45–S47.

- Natarajan, L. and Cho, H. (2022) Place Profiles: Localizing Understandings of Disadvantage. Working Paper: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Available at: https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/working-papers/place-profiles-l....

- Ng, M.K. (2002) From a Special Economic Zone to a smart sustainable city: the power of strategic spatial planning in Shenzhen. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 581–593.

- Olsen, D. (1979) The Growth of Victorian London. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Parkinson, M. (2022) ‘Make no little plans’: the incomplete but continuing renaissance of Liverpool. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 493–511.

- Quadri, Z. (2022) War is still a racket: private military contracting, US Imperialism, and the Iraq War. American Quarterly, 74(3), pp. 523– 543.

- RTPI (Royal Town Planning Institute) (2019) The Planning Profession in 2019. Available at: https://www.rtpi.org.uk/media/5889/theplanningprofessionin2019.pdf.

- Saeed, Z.O., Almukhtar, A., Abanda, H. and Tah, J. (2022) Mosul city: housing reconstruction after the ISIS war. Cities, 120, 103460.

- Sawyer, K. (2012) Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stafford, S. (2022) The Future of the Planning Profession. Lecture given at Reading University, 16 March. Available at: http://samuelstaff ord.blogspot.com/2022/03/the-future-of-planningprofession.html.

- Ward, S. (1994) Planning and Urban Change. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

- Wray, I. (2016) Great British Plans: Who Made Them and How They Worked. London: Routledge.

- Wray, I. (2019) No Little Plans: How Government Built America’s Wealth and Infrastructure. Lonson: Routledge.

- Wray, I. (2020) The essential state: pandemic, norms and values and the new authoritarianism. Planning Theory, 20(4). https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1473095220969626.

- Yaro, R. (2022) How Regional Plan Association – New York’s civic-led group – ‘gets things done’. Built Environment, 48(4), pp. 512–527.

- Zaretsky, E. (2012) Why America Needs a Left: A Historical Argument, Cambridge: Polity.