A New Dawn for Australia’s Cities?

On 11 October 2015 Malcolm Turnbull, who had been Prime Minister of Australia for less than a month at the time, committed federal funding of A$95m towards the cost of extending a light rail network on the Gold Coast in the northern state of Queensland. This funding announcement, while modest in its scope, marked a major change in federal government attitudes to public transport. Turnbull’s predecessor as Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, had preferred a transport policy which limited national government funding to road projects, on the basis that:

… there just aren’t enough people wanting to go from a particular place to a particular destination at a particular time to justify any vehicle larger than a car, and cars need roads.*

Turnbull, like Abbott, leads a coalition government comprised primarily of the Liberal (which in Australia means conservative) Party, with support from the smaller National Party, a party which derives its support mainly from voters with interests in agricultural and rural issues. National urban policy in Australia over the past half century or so has been the exclusive concern of the Labor Party which pursued ambitious strategies of planned decentralization and public land acquisition in the 1970s when it held government under the charismatic leadership of Gough Whitlam. Labor also adopted a range of urban policies during its periods in power in the early 1990s and again between 2007 and 2013. Most Australians live in cities and there is an argument, therefore, for regarding a focus on cities as a legitimate concern for national governments The consistent approach of the Liberal-Nationals, however, has been to refuse any responsibility for the planning of Australia’s cities and to regard this as the responsibility of state governments.

The suburban fringe, 2015 (Photo: Steve Hamnett)

Old and New in Australia’s inner suburbs (Photo: Steve Hamnett)

Australian suburban image (Photo: Steve Hamnett)

But this may now have changed. In addition to a change in transport policies, Turnbull, when revealing the make-up of his new cabinet, conceded that Australian cities ‘have been overlooked … historically from the Federal perspective’ and announced the appointment of a new Minister for Cities and the Built Environment, charged with ensuring that Australian cities are well-planned, provided with ‘world class’ digital and physical infrastructure as well as being environmentally sustainable. To these ends the Minister for Cities is required to work with the Environment Minister to develop a new agenda for cities, in co-operation with state and local governments.

Environmental policy is also likely to change under the Turnbull government. Between 2008 and 2009, Turnbull was briefly leader of the Liberal-National coalition in opposition. However in November 2009 he lost the leadership to Abbott, because of his support for a carbon pricing scheme which the then Labor Government was seeking to introduce. Abbott was notorious for declaring around that time that ‘climate change is crap’ and later, when in office, for endorsing a very modest policy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions which was limited in ambition somewhat by his belief that ‘coal is good for humanity’. Partly because of this belief, Abbott also sought a substantial reduction in Australia’s national renewable energy target, despite the obvious and significant opportunities that Australia’s climate and landmass offer, for wind and solar power in particular. Turnbull, however, has consistently supported the idea of some form of carbon pricing to reduce emissions and has argued for market-based incentives which can encourage a faster shift towards renewable energy technologies.

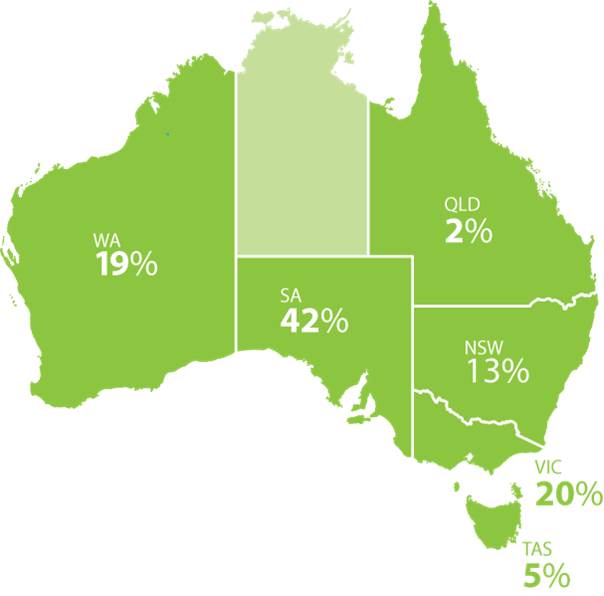

Wind turbines by Australian State. (Source: Clean Energy Council Renewable Energy Database, 2012)

Australia is amongst the highest emitters of greenhouse gases per capita on the planet. It is also a highly-urbanized society with most of its people concentrated in a small number of large, sprawling, low-density, car-based coastal cities. Its current population of around 24 million is likely to double in the course of the present century and, on some projections, could exceed 70 million by 2101. The need for serious national urban and climate change policies seems urgent to a growing number of observers and, while these are very early days, the arrival of the Turnbull government provides some grounds for hoping that these are on their way.

In March 2016, Built Environment will publish a special issue entitled ‘Australian Cities in the 21st Century’ which will provide an update on Australia’s national (sub)urban policies, as well as exploring issues of affordable housing, transport, planning for remote mining towns and a range of other policy challenges facing ‘the Lucky Country’.

Stephen Hamnett

* Abbott, T. (2009) Battlelines. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, p.74.

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs and tweets on this theme!