Australian Cities in the 21st Century: Suburbs and Beyond

About this issue

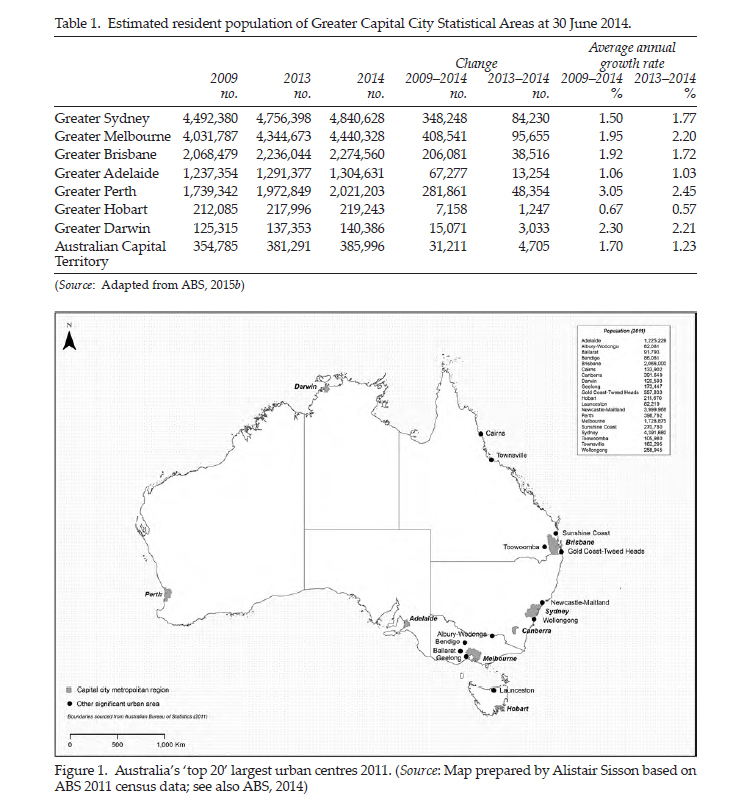

Summary

The editors and contributors to this issue look at the challenges facing Australian cities – from climate change to ageing populations; from public transport planning to housing supply; and from to disaster risk to demographic change – in each case emphasizing the need for systematic evidence-based policy-making and monitoring to underpin urban planning and policy.

The Growth and Form of Australian Cities

Foundations: A Suburban Nation

Planning Suburban Cities

In the article which follows, Gurran and Phibbs focus more closely on the link between housing affordability and the planning system, drawing on evidence from the Sydney metropolitan area. Australia has long been a nation of homeowners, with nearly 70 per cent of households owning or purchasing their homes and the balance predominantly renting in the private sector. However, the dream of homeownership seems increasingly inaccessible to young people as demand for housing outstrips supply. Land-use planning is regularly blamed as the key reason for constraining supply through policies such as urban growth boundaries and also as a consequence of the time that it takes to gain planning permission (Moran, 2006). This has led to continuing pressure to reform the planning system, generally in ways that make it easier for developers to gain approval, with reduced opportunities for communities to be involved in planning decisions and fewer rights of appeal for third parties. Gurran and Phibbs examine the relationship between planning reforms and housing supply in New South Wales (NSW) over the period since 2000, drawing upon detailed empirical data and analysis of changing trends affecting the housing market, rates of new production and affordability outcomes for lower income groups. Their analysis demonstrates the inter- dependence between rising house prices and rates of new housing supply. It also shows that, despite the constant criticism over recent years, it is clear that the NSW planning system is capable of responding to changes in housing demand. The empirical data suggests that demand side factors – particularly finan- cial deregulation, tax incentives and reductions in interest rates – offer much more plausible explanations for price inflation than the assumed constraints imposed by the planning system on new housing supply.

A decade or so ago, in his book Australia Fair, the great Australian urbanist Hugh Stretton gave this damning picture of housing in Australia:

Thus, the richer we get, the longer our queues for public housing grow, and the higher the prices rise of a stock of market housing that grows more slowly than the number wanting it. Whether for market demand or for human need, we have a serious failure of supply and no current program, public or private, to correct it. (Stretton, 2005, p. 123)

Gurran and Phibbs are no more optimistic. While it seems clear from their analysis that changes to the current taxation system rather than reforms to the planning system could have a much greater effect in reducing house price inflation, such changes face strong political opposition from housing investors and developers. They find that much of the contemporary public debate about Australian housing markets is driven by politics, ideology and vested interests, paying insufficient attention to the range of available empirical evidence. This echoes Burke’s concerns in rela- tion to public transport investment. They con- clude that, until this changes ‘the Australian dream of homeownership is likely to prove elusive for younger households’.

The paper by Ruming and Goodman offers a further complementary perspective on planning system reform by demonstrating how this forms part of a much broader shift towards an increasingly neoliberalized model of urban governance, characterized by reduced state involvement, deregulation, an increased emphasis on market mechanisms and a push for more speed and efficiency in economic systems, including planning and urban development. Like most other authors in this collection, Ruming and Goodman explore the significance of Australian federal, state and local governance arrangements to the character and effectiveness of planning systems and policies. They note a growing, but incremental and desultory, interest by federal governments in planning as a means of facilitating economic development and show how this has been subsumed into the reform agenda of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG). This includes attempts to ‘harmonize’ planning systems, especially within the capital cities, via the introduction of standardized planning provisions; reduced appeal rights; the delegation of approval authority away from elected councillors to council staff; and independent expert assess- ment panels. A further trend at the local level is towards local government amalgamations in several states to reduce the number of small local councils.1 The overall thrust of these reforms, they suggest, is to give priority to short-term economic growth over long- term strategic policy issues.

Ruming and Goodman note, from a review of international literature, that urban planning straddles the divide between the push for capital accumulation and deregula- tion under a neoliberal urban governance model and traditional welfare state purposes of maintaining participation, equity and justice. Their paper then explores the partic- ular characteristics of recent planning system reform initiatives in the Australian states of New South Wales and Victoria. These comparative case studies reveal a ‘rather haphazard progress towards uncertain, and at times shifting, goals’. While ‘cutting red tape’ in the interest of efficiency seems always to be a priority, other principal purposes of reform shift from time to time between deregulation, faster decisions, predictable outcomes and the political need to appease communities concerned at the environmental impacts of development and at their loss of rights to be consulted or to appeal against planning decisions. Ruming and Goodman also question whether there is any persuasive evidence that planning system reform has led to improved economic performance. An increase in the number of development applications approved occurs from time to time but, as Gurran and Phibbs also suggest in their paper, this may be a product of broader housing market conditions, which make residential development more profitable in a period of rising housing prices, rather than a direct consequence of new planning procedures.

Wellbeing, Ageing and Diversity in the Suburbs

The next three papers are linked by a focus on the changing character of Australian cities and suburbs, looking in turn at health and wellbeing, the particular challenges of an ageing population, and the implications of increasing cultural and religious diversity. Australians generally enjoy good levels of health, but there is evidence of a growing burden of chronic disease. This is primarily associated with high levels of obesity, poor nutrition and sedentary lifestyles, all of which are affected in some ways by the nature of built environments. Susan Thompson and Jennifer Kent draw upon a rich and growing body of work which shows how the places where we live our daily lives contribute to our physical and mental health to the extent that they allow people to be physically active, to have access to fresh, affordable food, and to be socially connected. Their paper traces the progress made to date by Australian planners and governments at various levels to create health supportive environments which can lower the risks from many of the most prevalent (and expensive) causes of morbidity and mortality in the modern world.

The low residential densities and high levels of car dependency in Australian cities do, of course, foster decreased rates of physical activity and socially isolated ways of living. Infrequent and sometimes non- existent public transport, and long distances between employment, retail and service outlets exacerbate this situation. Conversely, Thompson and Kent argue that higher resi- dential densities, with locally situated com- mercial and community destinations and a well-designed and culturally relevant public realm, can sustain active modes of transport such as cycling and walking and can enable people to live, work and be active within their communities. The paper looks in some detail at ‘active transport’ strategies to encourage walking, cycling and the use of public trans- port. The authors find the evidence persua- sive that active transport policies are clearly having positive health and other benefits. Other important themes developed by Thompson and Kent include the need to build collaborative partnerships with health professionals and to deliver healthy planning as a core module within the planning cur- riculum at Australian universities.

The relationship between health and the built environment is also at the core of the paper by Sara Alidoust and Caryl Bosman, which examines some of the particular challenges faced by Australian cities and suburbs as their populations become older. Between 1994 and 2014 the proportion of Australia’s population aged 65 years and older increased from 11.8 per cent to 14.7 per cent, while the proportion of people aged 85 years and older almost doubled from 1 per cent to 1.9 per cent. Alidoust and Bosman observe that an ageing population presents significant economic, social and policy challenges in a wide range of areas including a reduction in the size of the work force; an increase in public sector expenditure, including pensions and health care; and the demand for an appropriate housing stock. An ageing population is not just an Australian phenomenon – governments around the world have extended the retirement age and introduced other policies to encourage people to stay in the workforce, to encourage more independence on the part of older people and to allow older people to remain in the family home. These policies intersect with the aspirations of the World Health Organization to achieve ‘Age-Friendly Cities’ – urban en- vironments that foster health and security for older people and that are responsive to their varying needs and capabilities (WHO, 2007).

It is against this policy framework that Alidoust and Bosman explore the develop- ment of policies for older people at various levels of government in Australia. The paper then examines the degree to which Australian cities actually provide the physical and social requirements for age-friendly cities, drawing on qualitative case study research conducted in the City of Gold Coast, Queensland. Particular attention is given to the idea of accessible environments, including access to affordable public transport, and to the need to provide a range of opportunities for social engagement to maintain the mental wellbeing of older people.

With a population of about half a million, the Gold Coast is one of the fastest growing cities in Australia (see also the paper by Burton in this issue). In 2013 15 per cent of its population was over 65. Focusing on three suburbs with broadly similar proportions of elderly people but differing from each other in their population density, built form and levels of accessibility, the authors found an overall lack of accessible and frequent public transport and a corresponding reliance on the private car, with distances to most destinations regarded as being too great to walk. An important general conclusion of the paper was that it is difficult to meet the require- ments for an ‘Age-Friendly City’ in the sorts of suburbs examined in the case studies. A concern for meeting the needs of elderly residents leads, therefore, to advocacy of policies which have more general support from planners, including mixed-use develop- ments with higher levels of accessibility to a range of public services and facilities along with greater opportunities for reliance on active modes of travel, including public transport, for ageing residents.

Paul Maginn and Stephen Hamnett examine the changing multicultural character of metropolitan Australia. Using country of origin and religious affiliation as markers of cultural diversity, they profile key capital city region populations across Australia and ponder some of the main implications this has for both strategic metropolitan planning and local statutory planning. While Australia prides itself on being a multicultural nation and the demographic data clearly show a highly diverse population, recognizing diversity and the particular needs of different groups does not seem to be explicitly artic- ulated in planning policy. In essence, plan- ning at state and local levels adopts a ‘colour-blind’ approach when it comes to acknowledging that metropolitan and local populations are becoming increasingly diverse. This is argued to be largely a function of the physical land-use and ‘techno-rational’ style of decision-making that still underpins Australian planning practice. This ‘colour- blind’ approach also resonates with national and state multicultural policy frameworks which, although recognizing difference and diversity, promote a unified and singular ‘Australian’ identity. Whilst both of these policy approaches are underpinned by the intent to treat different groups ‘equally’, planning issues do not exist in political vacuums. As Australia has become increas- ingly diverse in cultural and religious terms, multiculturalism has become a highly politic- ized issue across all levels of government. Despite the rhetorical political commitment to multiculturalism, Maginn and Hamnett highlight that planning for places of worship for Muslim, Hindu (Bugg, 2014) and Christian (Beer, 2009) communities remains a highly vexed issue (Dunn 2001, 2004). Whilst opposition to minority religious and other land uses may be rooted in concerns about tech- nical planning issues, ultimately a complex mix of broader social and geo-political processes is at play.

The Vulnerability of Australian Cities to Climate Change and 'Natural Disasters'

Jon Kellett’s paper looks at Australian cities and climate change – an issue dubbed as the ‘great moral challenge of our generation’ by former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2007.2 Australia is vulnerable to a number of significant effects of climate change, including rising sea levels, floods, heat waves, bushfires, cyclones and droughts. The paper discusses these threats and then reviews the policy responses which, in recent years, have been polarized between the major political parties at the federal level on how to respond to the need to reduce greenhouse gases. The Abbott government (2013–2015) gained international notoriety for its reluctance to pursue strong greenhouse gas reduction policies, but other governments have also faced the challenge of framing appropriate policies in a country which is amongst the world’s largest coal producers and also one of its biggest per capita carbon polluters.

The discussion of how to respond to climate change comes back once again, in part, to the form of Australian cities and their high levels of car dependency. Kellett points out that space has always proved an attractive attribute of Australian residential areas, with both allotment sizes and house floor areas historically much larger than in Europe or Asia. In 2009 new freestanding houses in Australia had a median floor area of 240 square metres, making them the largest in the world. All the indicators are that Australia is living well beyond its environmental means but climate mitigation policy threatens to impact on the prosperous lifestyles of many and is resisted accordingly. The paper asks whether the historic land-use patterns of Australian cities and the behaviours of their residents represent ingrained characteristics that pose major obstacles to appropriate adaptation.

Kellett’s paper points to the contrast between the poorly developed state of national policy designed to reduce carbon pollution and the more encouraging progress made by some state and local governments. The state of South Australia, for example, now obtains more than a quarter of its energy from wind power and other states have also made progress in encouraging a shift towards renewable sources of energy. Most state metropolitan plans now favour varying degrees of urban consolidation and higher densities along rail corridors and around activity centres. As commuting distances fall, more trips are made by public transport, bicycle and walking, and the floor areas of dwellings become smaller, the hope is that urban greenhouse gas emissions will reduce. Kellett notes, however, that while there are multiple potential benefits from such policies, the pace of observable change has not been encouraging to date. And even when heroic assumptions are made in metropolitan plans about the amount of new housing that might be provided as higher density apartments in transit-friendly locations, vast areas of suburbia remain unchanged, both physically and in respect of their zoning (see Gordon et al., 2015).

Kellett explains how, in parallel with the above efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emis- sions, the question of how urban form and land-use location might adapt to a changing climate has proved the focus of increasing debate. Kellett observes a high degree of overlap between policies relating to resilience and more wide-ranging concerns relating to urban sustainability. Recycling of water and waste, the collection of solar and wind energy, the use of green roofs and walls to ameliorate temperature extremes, and the application of energy efficient building techniques and devices, represent examples of specific and relatively easy to achieve technical solutions which may improve both resilience and sustainability. Kellett points out, however, that adapting to increased threats to the urban environment is not as simple as ‘having a good grasp of the available policy toolkit’. Rather, it requires fundamental shifts in the underlying drivers of behaviour which produce and manage urban development.

Kellett stresses the need for the federal government to set appropriate greenhouse gas reduction targets and, crucially, to demon- strate the political will to achieve these. Both have been lacking to date. Such top- down policy action demands reinforcement, moreover, by bottom-up initiatives that address both climate mitigation and adapta- tion. However, Kellett expresses a concern that at every level – local, state and national – climate change is proving a divisive political issue which is often seen as threatening economic development or existing quality of life, leading to a lack of consensus on how, or even whether, to respond. He concludes that ‘the pace of change lags behind the rhetoric and political will is shaky, despite Australian cities being some of the most globally vulnerable to multiple climate change driven threats’.

Alan March delves further into the history of disasters which have caused significant numbers of deaths and damage to property in Australian urban areas since the beginning of the twentieth century. The frequency of Australian disasters of national significance has increased since 1990 and especially since 2000. While many urban disasters have their origins in the natural world, March notes that it is now acknowledged that humans need to take more responsibility for the risks embodied in their settlements. The paper records some significant achievements in Australia in forecasting and providing early warning of some potential disasters through the work of bodies such as the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, Emergency Management Australia and Geoscience Australia.

March is critical, however, of the lack of use which planning agencies sometimes make of this information. For example, flood modelling indicates that significant parts of Australia’s coastal settlements are at risk from sea level rise, but this has not been translated into consistent coastal planning strategies in all states. March also points to instances of short-term political pressures prevailing over longer-term disaster reduction strategies. In the aftermath of the major bushfires in Victoria in 2009, for example, a Royal Commission found that certain areas were too risky to be built upon or to be used for any purposes. This was in direct contrast to the promise of the then state Premier, who had indicated immediately after the fires that all properties could be rebuilt, and facilitated substantial changes to the Victorian planning provisions to allow for this. March gives a further example of floods in Queensland in 2010–2011, which caused substantial areas in Brisbane to be inundated. Many of these had been identified as flood-prone after the 1974 Brisbane floods in which a number of people drowned, but since then development had been allowed in these areas, exacerbating the impacts of the more recent floods.

A key theme of March’s paper is the need for a more integrated approach to the planning of settlements to reduce the risks of disasters and also to allow for more effective and better co-ordinated responses when disasters inevitably occur. He observes that, at present, an institutional policy gap exists between planning bodies and emergency management agencies with the former being forward-looking and pursuing improved integration while the latter still retain their traditional focus on particular hazards and events and on ‘response-and-recovery’ processes. March also notes once again the barriers to integration inherent in Australia’s federal arrangements, under which each state has its own emergency legislation, agencies and funding, with federal monies commonly allocated to states through the competitively funded National Emergency Management Projects scheme. March is optimistic about the potential for more integrated responses in future, however, following the adoption in 2011 by the Council of Australian Govern- ments of an overarching National Strategy for Disaster Resilience oriented to the reduction of vulnerability, increased community resili- ence, and the promotion of shared responsi- bility and co-operation between public, private and community sectors. At the time of writing his paper, a new national peak body had also just been announced by the Federal Minister for Justice, the ‘Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience’ (AIDR) which is intended to address longstanding problems of fragmented knowledge and training across the emergency management and disaster sectors of Australia.

Beyond Suburbia

The final two papers in this issue look at towns and cities beyond the major state capitals. Matthew Tonts, Fiona Haslam McKenzie and Paul Plummer show how the resource ‘super-cycle’ has had profound impacts on settlements in the north-west of Western Australia, including giving rise to distinctive suburban and housing forms to meet the needs of large numbers of ‘FIFO’ (fly-in/fly- out) workers.

The opening decade of the twenty-first century saw some of the most rapid economic expansion in Australia’s post-Federation history. This growth was linked primarily to a resource boom or ‘super cycle’, where rising levels of industrial activity and consumption amongst Australia’s largest trading partners, and China in particular, created increased demand for iron ore, petroleum products, bauxite, gold and nickel, leading to significant increases in commodity prices. These price signals led to a rapid inflow of capital for new resource projects and a substantial increase in production. Between 2000 and 2012, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in Australia grew by 44 per cent, while Gross National Income grew by 63 per cent. In the Pilbara in northwest Western Australia, one of Australia’s most significant resource regions, the gross value of production from natural resources in 2014 was in the order of A$94 billion, with iron ore contributing A$62 billion of this and offshore petroleum products a further A$27 billion. This super-cycle had a profound effect on the structure of Australia’s space economy, leading to a widespread discourse on Australia as a ‘two-speed’ economy based on the distinction between states with resource-led economies (principally Western Australia and Queensland) and the rest. The resource-rich states saw substantial increases in population, with Western Australia in particular experiencing a 26 per cent increase in population between 2001 and 2011 (from 1.83 million to 2.6 million).

The authors describe the impacts of this growth on the settlement system of Western Australia. Perth, the capital, experienced significant growth as the site of most of the resource industry corporate headquarters and service industries, as well as the home of many workers who took part in FIFO com- muting to remote mine sites. The emphasis of their paper, however, is on the consequences of the boom for small, remotely-located settlements. Their focus is on the Pilbara region, and particularly on the towns of Karratha and Port Hedland, critical hubs in the nation’s iron ore and petroleum industries.

The authors draw on a substantial body of research to explore several dimensions of the resource boom and its impacts on the Pilbara region. The total population of the Pilbara grew rapidly over the decade between the 2001 and 2011 censuses, rising from 39,461 to 62,736 – an increase of 59 per cent. They examine the vulnerability of resource towns in the face of the inevitable volatility that results from changing commodity prices and the finite nature of resources. They also analyse the contentious debate around the advantages and disadvantages of FIFO work arrangements, whereby employees live on site for a period of weeks before returning home on leave. On the one hand, FIFO results in the economies of remote cities and towns failing to capture fully the economic and social opportunities presented by resource extraction. On the other, FIFO offers workers greater choice and flexibility, particularly in the context of possible future mine closures. Moreover, it reduces the cost of providing services and infrastructure in remote areas.

Tonts, Haslam McKenzie and Plummer report on the middle ground which has emerged during the recent boom which acknowledges the benefits of well-planned temporary worker accommodation in limiting impacts on local housing and employment markets, while deriving as much economic benefit for local settlements as possible. They also describe in some detail the ‘Pilbara Cities Initiative’. This sought to use the boom to transform some of Western Australia’s remote ‘frontier’ regional towns by reducing the level of population turnover associated with resource employment through policies intended to strengthen their infrastructure and improve their ‘liveability’. The paper also explores the social consequences of rapid population growth and the impact on house prices – by 2012 median house prices in Karratha and Port Hedland were more than A$1 million and rents reached more than A$2,000 per week for a three bedroom house, making housing unaffordable for those on low and even middle incomes.

Tonts, Haslam McKenzie and Plummer also reflect on the end of the current resources boom which has seen iron ore prices fall from a peak of over US$160 a tonne in 2011 to less than US$40 in December 2015, with consequent retrenchments in resource-related and other industries, outmigration and a decline in house prices and rents. The paper ends by drawing some lessons from the Pilbara Cities Initiative for multi-level plan- ning approaches which can respond to the inevitable volatility and dynamism of resource-based communities. As well as lessons for Australia, the observations in this paper offer cautionary tales for local communities and policy-makers in other resource-fuelled economies and spaces.

The final paper, by Paul Burton, looks at the City of Gold Coast in Queensland as an example of an ‘adolescent city’. The City of Gold Coast only came into existence in 1959 as a separate local government entity. It is now Australia’s sixth largest city with a resident population of a little over half a million people and, as noted earlier, on present trends it may be larger than Adelaide, Australia’s fifth largest city, before 2050. As a tourist city, the Gold Coast’s population also increases by about 40,000 visitors every night of the year.

When the Gold Coast was growing rapidly during the 1970s and 1980s, the style of gov- ernment in Queensland was memorably described by Patrick Mullins of the Univer- sity of Queensland as one of ‘political authori- tarianism, socially-repressive fundamentalism and hillbilly panache’ (Mullins, 1980, p. 212). Burton notes that some of the ‘great men’ of the Gold Coast were property developers who thrived under this regime, and several have done so since, leaving the city with an enduring reputation as ‘a sunny place for shady people’.

Some see the Gold Coast, with its mix of high-density apartment complexes strung along the coastline, ‘McMansion-esque’ in- land canal estates and ‘traditional’ suburban housing, as a model for emergent cities. Others see it as the epitome of unregulated and unsustainable urban growth. Burton takes the innovative approach of analyzing the growth and future prospects of the City of Gold Coast against a framework derived from theories of human development, in which adolescence is used as a metaphor to characterize rapid physical growth, identity confusion, hubris and egocentricity, entrepreneurial zeal and emergent forward thinking. He speculates about the eventual transition of the city to maturity, as well as the risks of failing to make such a transition. The paper also considers the usefulness of adolescence as a metaphor for the trajectory of cities elsewhere. Burton observes that, if the total population of Australia continues to grow strongly, as suggested in the projections from the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided earlier, then the distribution of that enlarged population will become significant. Without a plausible national urban policy it is most likely that much of this population growth will be concentrated initially in Sydney and Melbourne. But, as housing and congestion costs continue to rise in these cities, it is also likely that some new migrants to Australia will consider moving to smaller cities and that these will experience some of the growing pains felt in the Gold Coast over the last 50 years. In that case, what has been a relatively limited experience of adolescent urbanism in Australia may well become more commonplace with some of the lessons learned by the Gold Coast taking on a wider relevance.

Metropolitan Planning and Governance

A recurring theme across the papers in this collection is the ‘governance gap’ between the contemporary planning challenges facing Australian cities and the planning arrange- ments and policies in place at various levels of government. In 2008, the most recent issue of Built Environment (Volume 34, no 3) to have a focus on Australian cities took stock of the crop of strategic plans for Australia’s major cities around that time. The introductory paper to that issue noted that a central strategy was the aspiration to make Australian cities more compact, thereby reducing the amount of travel by car, with most major cities aiming to accommodate at least 60 per cent of future urban development within a metropolitan growth boundary, published or de facto (Forster and Hamnett, 2008, pp. 248–249). There was also a renewed emphasis on ‘corridor planning’, with higher density redevelopments proposed along rail corridors linking major activity centres. The latter were also intended, amongst other things, to provide a better ‘jobs–housing balance’, especially in middle and outer suburbs. The authors displayed some scepticism about how readily or quickly Australia’s suburban cities, with their dispersed and differentiated residential patterns and their complex journeys to work, could be adapted to these metro- politan planning imperatives. They suggested that levels of car use would remain high, even under the more heroic assumptions made about shifts to public transport and an increase in walking and cycling. Forster and Hamnett also expressed a general concern that, while metropolitan strategies acknowledged problems of housing afford- ability and locational disadvantage, there was little that the plans by themselves could do to tackle the principal causes of these problems (Ibid., p. 249).

In a recent paper Raymond Bunker (2014) has provided a detailed update on how plans for ‘the compact city’ have fared over the past decade or so. He found that such an assessment was not as easy as it might have been because of the lack of much effective monitoring of the progress made towards the long-term housing targets established in metropolitan plans. Nevertheless, drawing on the best sources of information available,3 Bunker conducted a systematic analysis which showed some fairly ‘patchy’ results. Overall, he found that a much wider variety of dwelling types is now being constructed in a wider range of locations, and building of medium-density housing has increased generally. Ambitious targets for infill develop- ment, however, have not been met in most cities and growth at the urban fringe remains strong, aided by the continuing release of land for development within generous and regularly revised urban growth boundaries. Some increased use of public transport was noted, but this tended to be mainly in journeys to the central city and the better- served inner suburbs. The strategy of concentrating mixed uses and activities in a hierarchy of activity centres, meanwhile, has been most effective in a few major locations, but employment in middle and outer suburbs continues to be widely dispersed (Bunker, 2014, pp. 458–459).

Overall, Bunker noted the paradoxical feature of recent metropolitan strategic plans that, while these are trumpeted as ‘long-term plans’ – Melbourne 2030, Directions 2031 and so on – they tend to have a fairly short shelf- life and are frequently revised or reissued, often after a change of state government occurs. This reflects the reality that metro- politan plans have become primarily political statements, setting out the urban priorities of the current administration. Bunker also noted, as do the papers by Gurran and Phibbs and by Ruming and Goodman in this issue, the reliance by state governments, under pressure from the private development sector, on reforms to planning and zoning systems to achieve the principal aims of metropolitan plans to the exclusion of a better understanding of housing and other metro- politan change processes and the impacts of alternative policies.

The last few years have seen growing support for the idea that more effective metro- politan planning in Australia will require changes to the governance arrangements for cities and for collaborative policy relation- ships between all levels of government. For example, a recent study of employment patterns in Western Sydney by Fagan and O’Neill (2015) confirmed that, despite the objectives of metropolitan planning strategies since the 1980s, levels of regionalization and self-sufficiency in the Greater Western Sydney (GWS) labour market have fallen and out- commuting rates and travel distances to work have increased. Poor access to employment has also raised unemployment levels, led some workers to withdraw from the labour market, and generally exacerbated labour market inequalities. Fagan and O’Neill draw the following conclusion for governance arrangements:

A major implication of our analysis is that no single level of government is capable on its own of delivering the composite of policies and strategies needed to address the growth needs for the GWS labour market. National economic and fiscal policies establish the settings within which the demand for labour ensues. National immigration policies influence the demography of GWS in major ways. State government-led expenditure on infrastructure steers the urban structure of GWS and defines all sorts of land use and travel possibilities. Metropolitan planning strategies provide the important details that give the GWS economy its geography and enable it to run. State government policies determine the provision of education and health and other key services, and the employment that these services bring. Finally, local government is crucially important in the provision of community and local services, important for both employers and households. And there are many other examples. The point is clear, though: it is the raft of government action acting together that ensures successful labour market outcomes. (Fagan and O’Neill, 2015, pp. 71–72)

In 1992 a committee of the lower house of the Australian Parliament, the House of Representatives, conducted an inquiry into the national ‘Pattern of Urban Settlement’ and into the potential for urban consolidation. In its report, the committee noted that it had experienced some difficulty in reaching conclusions because of the uncertain and conflicting nature of the evidence provided to it and suggested two principal reasons for this uncertainty:

First, unlike most other advanced industrial countries, Australia does not have a definite, strong national urban and regional strategy; as a result, its perspective on issues is sectoral rather than national. Secondly, there is no adequate collection of research data on which to base significant analysis. These factors limited the Committee’s ability to address the full extent and complexity of urban problems in Australia. (House of Representatives Standing Committee for Long Term Strategies, 1992, p. 78)

Gleeson et al. (2010; 2012) note that, in addition to the lack of national urban policy which has been referred to earlier, Australia is unusual amongst developed countries in its lack of metropolitan governments – Brisbane is the only exception. As a consequence, there is an absence of accountable institutions at the metropolitan scale capable of conceiving and co-ordinating the integrated strategies required for the planning of urban renewal, supporting the development of centres across metropolitan areas, making improvements to access, and pursuing economic and employment strategies (see also Randolph, 2015).

In relation to the issue of research data on Australia’s cities, Randolph suggested in 2013 (more than two decades after the House of Representatives Inquiry referred to above) that metropolitan strategies remain ‘… bedevilled by a lack of understanding of how the cities planned actually work’ (Randolph, 2013, p. 131). In fact, the amount and quality of research available on Australian cities has grown substantially in recent years, with the development of a small number of highly regarded urban research centres, the substantial body of work produced by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), and the biennial research conferences on the State of Australian Cities which have been organized since 2003.4 The reasons why much of this outpouring of research still fails to underpin or influence policy to a sufficient degree are complex and have received a good deal of attention recently (see, for example, Troy, 2013; Bunker, 2015; Taylor and Hurley, 2015). But Gleeson et al. see a vital role for new metropolitan level planning bodies to draw together research on metropolitan development and to undertake much better and finer-grained monitoring of short-term progress towards the long-term aspirations of metropolitan plans. As the preferred vehicle in the short-term for effective metropolitan governance they argue for the establishment of a metro- politan commission for each major city with clear responsibility for issues and places of metropolitan significance such as principal activity centres, major public transport corri- dors and employment nodes. Such commis- sions would need to be established collab- oratively by the Commonwealth, state and local governments. Importantly, they would also provide a focus for engaging the public in discussion of metropolitan planning issues on the basis of a representational governance model of the sort which underpins the much- admired Greater Vancouver Regional District (now Metro Vancouver) in Canada (Gleeson et al., 2010, p. 13; Metro Vancouver, 2015)

A number of the papers in this issue have mentioned some positive steps taken recently by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) towards more collabora- tive arrangements between levels of government for metropolitan planning. COAG is the peak inter-governmental forum in Australia and its members are the Prime Minister, the state and territory Premiers and Chief Ministers, and the President of the Australian Local Government Association. Its role is to promote policy reforms of national significance requiring co-ordinated action at all levels of government. In December 2009, at a time when the Rudd Labor government was in power, COAG agreed to establish criteria for capital city planning systems and the preparation of strategic plans for metro- politan areas (COAG, 2009). By 2012, all states were required to have such plans in place and the intention was that all future infrastructure funding decisions would need to meet the COAG criteria. In 20115 the COAG Reform Council (2012, pp. 11–12) recommended that capital city planning needed to have a better evidence base and that more emphasis should be placed on monitoring the performance and outcomes of plans. Also in 2011, the Labor Government (by then led by Julia Gillard who replaced Rudd as Labor leader in 2010)6 published a promising statement of intent for a national urban policy. However, as several papers have described, when the Abbott-led Liberal/National coalition government came to power in 2013, it moved quickly to wind back Labor’s urban policies, scrapped the Major Cities Unit established by Rudd, and returned planning responsibilities to state governments apart, as noted by Burke, from major road funding. This was viewed pessimistically by many urban observers, including Burton and Dodson, contributors to this issue, who concluded that Australian cities were likely to:

… continue to lumber forward, struggling to cope with housing shortages, jobs located away from major centres of population and ever-increasing congestion. The prospect of imaginative, well-designed, properly resourced urban policy with sufficient bipartisan support to survive for decades looks as distant as ever in contemporary Australia. (Burton and Dobson, 2014, p. 259)

In late 2015, however, events took another turn when, as described earlier, the Liberal Party replaced Abbott with Malcolm Turnbull as its leader. Turnbull quickly abandoned several of Abbott’s more extreme positions, such as his opposition to renewable energy projects and his reluctance to provide Com- monwealth funding to public transport projects. He also appointed a Minister for Cities and the Built Environment – noteworthy as the first such portfolio ever estab- lished on the conservative side of Australian politics. The first Minister for Cities appointed, Jamie Briggs, did not hold the position long enough to have much impact, being forced to resign in December 20157 and the Cities portfolio became the responsibility of Greg Hunt, the Minister for the Environment who, shortly before entering government, had expressed his own support for Integrated Planning Commissions8 for each capital city which:

… continue to lumber forward, struggling to cope with housing shortages, jobs located away from major centres of population and ever-increasing congestion. The prospect of imaginative, well- designed, properly resourced urban policy with sufficient bipartisan support to survive for decades looks as distant as ever in contemporary Australia. (Burton and Dobson, 2014, p. 259)

In late 2015, however, events took another turn when, as described earlier, the Liberal Party replaced Abbott with Malcolm Turnbull as its leader. Turnbull quickly abandoned several of Abbott’s more extreme positions, such as his opposition to renewable energy projects and his reluctance to provide Commonwealth funding to public transport projects. He also appointed a Minister for Cities and the Built Environment – noteworthy as the first such portfolio ever established on the conservative side of Australian politics. The first Minister for Cities appointed, Jamie Briggs, did not hold the position long enough to have much impact, being forced to resign in December 2015 7 and the Cities portfolio became the responsibility of Greg Hunt, the Minister for the Environment who, shortly before entering government, had expressed his own support for Integrated Planning Commissions8 for each capital city which:

… should involve all three tiers of government and … should draw from the planning, social and business sectors. Most significantly, they should be bipartisan. I would regard them as standing bodies, which would ideally include both the state planning ministers and shadow ministers, and representatives of the federal government and each of the relevant local councils. (Hunt, 2013, p. 255)

In conclusion, therefore, this issue is published at a time of some cautious optimism and considerable uncertainty about the future of policy for Australian cities. There seems broad agreement, at least amongst academic commentators, that current metropolitan plans and governance arrangements are not adequate to address the real problems of metropolitan regions and of the suburbs where most Australians live. Sound policy relies on rigorous evidence and policy evaluations but Australian cities continue to lack a systematic evidence-based policymaking and monitoring framework which can underpin urban planning and policy. To meet the social, economic, environmental spatial and political challenges of the twenty-first century a more sophisticated, collaborative and integrated urban planning research agenda is required, reflecting the reality that metropolitan regions are complex systems made up of key spatial entities – urban, suburban, and periurban – locally and globally interconnected to other spaces and processes. There are some signs at present that the need for better, more collaborative planning for Australian cities is increasingly appreciated on both sides of the political divide. Given the recent instability and volatility of national politics, however, it might be premature to herald a new dawn just yet.

… should involve all three tiers of government and … should draw from the planning, social and business sectors. Most significantly, they should be bipartisan. I would regard them as standing bodies, which would ideally include both the state planning ministers and shadow ministers, and representatives of the federal government and each of the relevant local councils. (Hunt, 2013, p. 255)

In conclusion, therefore, this issue is pub- lished at a time of some cautious optimism and considerable uncertainty about the future of policy for Australian cities. There seems broad agreement, at least amongst academic commentators, that current metropolitan plans and governance arrangements are not adequate to address the real problems of metropolitan regions and of the suburbs where most Australians live. Sound policy relies on rigorous evidence and policy evaluations but Australian cities continue to lack a systematic evidence-based policymaking and monitoring framework which can underpin urban planning and policy. To meet the social, economic, environmental spatial and political challenges of the twenty-first century a more sophisticated, collaborative and integrated urban planning research agenda is required, reflecting the reality that metropolitan regions are complex systems made up of key spatial entities – urban, suburban, and peri-urban – locally and globally interconnected to other spaces and processes. There are some signs at present that the need for better, more collaborative planning for Australian cities is increasingly appreciated on both sides of the political divide. Given the recent instability and volatility of national politics, however, it might be premature to herald a new dawn just yet.

NOTES

1. See, for example, NSW Independent Local Gov- ernment Review Panel (2013); NSW Government (2014); Metropolitan Local Government Review Panel (2012).

2. See http://australianpolitics.com/2007/08/06/ rudd-says-climate-change-is-great-moral-chal lenge.html.

3. Bunker’s analysis draws especially on the work of the Commonwealth Bureau of Infra- structure, Transport and Regional Economics, including BITRE (2013).

4. See http://apo.org.au/collections/soac-confer- ences.

5. The report was submitted in December 2011 but the official publication date was 2012.

6. And who was herself replaced by Rudd in 2013.

7. Briggs resigned following reported indis- cretions during an official visit to Hong Kong.

8. In November 2015, legislation to establish a Greater Sydney Commission was passed by the NSW parliament. Its first Chief Commissioner will be Lucy Turnbull, wife of the Prime Minister.

REFERENCES

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) (2013) Population Projections 2012–2101. Cat 3222.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Avail- able at: http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/mf/3222.0.

ABS (2014) Australian Historical Population Statistics. Cat 3105.0.65.001. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http://www.abs.gov. au/ausstats/[email protected]/PrimaryMainFeatures/ 3105.0.65.001.

ABS (2015a) Sydney Leads Race to Five Million. Media release 31 March. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http://www.abs.gov. au/ausstats/[email protected]/Latestproducts/3218. 0Media%20Release12013-14.

ABS (2015b) Australian Demographic Statistics. June Quarter. Cat 3101.0. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http://www. abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/3101.0/.

ABS (2015c) Overseas Born Aussies Hit a 120 Year Peak. Media release 29 January. Canberra: Aus- tralian Bureau of Statistics. Available at: http:// www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/latest Products/3412.0Media%20Release12013-14.

Beer, C. (2009) Pluralism and mega-churches: planning for changing religious community and built environment forms in Canberra. Urban Policy and Research, 27(4), pp. 435–446.

BITRE (Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics) (2013) Population Growth, Jobs Growth and Commuting Flows – A Comparison of Australia’s Four Largest Cities. Report 142. Canberra: Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development.

Bugg, L. (2014) Citizenship and belonging in the rural fringe: a case study of a Hindu temple in Sydney, Australia. Antipode, 45(5), pp. 1148– 1166.

Bunker, R. (2008) Metropolitan Strategies in Aus- tralia. City Futures Research Centre Research Paper 9. Sydney: University of New South Wales.

Bunker, R. (2014) How is the compact city faring in Australia? Planning Practice and Research, 29(5), pp. 449–460.

Bunker, R. (2015) Linking urban research with planning practice. Urban Policy and Research, 33(3), pp. 362–369.

Burton, P. (2015) The Australian good life: the fraying of a suburban template. Built Environ- ment, 41(4), pp. 504–518.

Burton, P. and Dodson, J. (2014) Australian cities: in pursuit of a national urban policy, in Miller, C. and Orchard, L. (eds.) Australian Public Policy: Progressive Ideas in the Neo-liberal Ascendancy. Bristol: Policy Press.

Collins, J. (2013) The changing face of Australian immigration. The Conversation, 8 June. Available at: https://theconversation.com/the-changing- face-of-australian-immigration-14984

COAG (2009) National Objective and Criteria for Future Strategic Planning of Capital Cities. Council of Australian Governments Meeting, 7 December. Available at: https://www.coag.gov. au/node/90#Att B.

COAG Reform Council (2012) Review of Capital City Strategic Planning Systems. Report to the Council of Australian Governments. Sydney: COAG Reform Council.

Davison, G. (1995) Australia: the first suburban nation? Journal of Urban History, 22(1), pp. 40–74.

Dunn, K. (2001) Representation of Islam in the politics of mosque development in Sydney. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Social Geografie, 92(3), pp. 291–308.

Dunn, K. (2004) Islam in Sydney: contesting the discourse of absence. Australian Geographer, 35(3), pp. 333–353.

Fagan, R. and O’Neill, P. (2015) Work, places and people in Western Sydney: Changing Suburban Labour Markets 2001–2014. University of Western Sydney: Centre for Western Sydney.

Forster, C. and Hamnett, S. (2008) The state of Australian cities: an overview. Built Environ- ment, 34(3), pp. 241–254.

Freestone, R. (2010) Urban Nation: Australia’s Plan- ning Heritage. Collingwood, VIC: CSIRO Publish- ing.

Gleeson, B., Dodson, J. and Spiller, M. (2010) Metro- politan governance for the Australian city: the case for reform. Issues Paper 12. Brisbane: Griffith University Urban Research Program.

Gleeson, B., Dodson, J. and Spiller, M. (2012) Governance, metropolitan planning and city- building: the case for reform, in Tomlinson, R. (ed.) Australia’s Unintended Cities: The Impact of Housing on Urban Development. Clayton, VIC: CSIRO Publishing.

Gordon, D., Maginn, P.J., Biermann, S., Sisson, A., Huston, I. and Moniruzzaman, M. (2015) Estimating the Size of Australia’s Suburban Population. Crawley, WA: University of Western Australia/PATREC. Available at: http://www. patrec.uwa.edu.au/publications#perspectives.

Hall, P. (2014) Foreword to Gleeson, B. and Beza, B.B.(eds.) The Public City: Essays in Honour of Paul Mees. Carlton, VIC: Melbourne University Press.

Hamnett, S. (2015) Hugh Stretton: ideas for Australian cities. Built Environment, 41(3), pp. 419–434.

Horne, D. (1998) The Lucky Country, 5th ed. Ring- wood, VIC: Penguin Books Australia.

House of Representatives Standing Committee for Long Term Strategies (1992) Inquiry into the Pattern of Urban Settlement. Canberra: Parliament of Australia.

Hunt, G. (2013) Achieving the 30- and 50-year plans for our cities. Urban Policy and Research, 31(3), pp. 255–256.

Jabour, B. (2015) The rise and rise of Barangaroo: how a monster development on Sydney har- bour just kept on getting bigger. Guardian Australia. 30 September. Available at: http:// www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2015/ sep/30/the-rise-and-rise-of-barangaroo-how-a- monster-development-on-sydney-harbour-just- kept-on-getting-bigger.

Logan, M.I., Whitelaw, J.S. and McKay, J. (1981) Urbanization: the Australian Experience. Mel- bourne: Shillington House.

McCarty, J. (1974) Australian capital cities in the 19th century, in Schedvin, C.B. and McCarty, J. (eds.) Urbanization in Australia: The 19th Century. Sydney: Sydney University Press.

Maher, C. (1985) The Changing Character of Australian Urban Growth. Built Environment, 11, 2, pp. 69–82.

Mees, P. (2000) A Very Public Solution: Transport in the Dispersed City. Melbourne: Melbourne Uni- versity Press.

Mees, P. (2010) Transport for Suburbia: beyond the Automobile Age. London: Earthscan.

Metropolitan Local Government Review Panel (2012) Metropolitan Local Government Review: Final Report of the Independent Panel. Perth: WA Government. Available at: http://metroreview. dlg.wa.gov.au/.

Metro Vancouver (2015) About Metro 2040. Burn- aby, BC: Metro Vancouver. Available at: http:// www.metrovancouver.org/services/regional- planning/metro-vancouver-2040/about-metro- 2040/Pages/default.aspx.

Moran, A. (2006) The Tragedy of Planning: Losing the Great Australian Dream. Melbourne: Institute of Public Affairs.

Mullins, P. (1980) Australian urbanisation and Queensland’s underdevelopment: a first empirical statement. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 4(2), pp. 212–238.

NSW Government (2014) A Blueprint for the Future of Local Government. Sydney: Office of Local Government. Available at: http://www. fitforthefuture.nsw.gov.au/sites/fftf/files/Fit-for- the-Future-A-Blueprint-for-the-future-of-Local- Government.pdf.

NSW Independent Local Government Review Panel (2013) Revitalising Local Government (Final Report). Available at: http://www.olg.nsw. gov.au/sites/default/files/Revitalising-Local- Government-ILGRP-Final-Report-October-2013. pdf.

Pinnegar, S., Randolph, B. and Freestone, R. (2015) Incremental urbanism: characteristics and impli- cations of residential renewal through owner- driven demolition and rebuilding. Town Plan- ning Review, 86(3), pp. 279–301.

Randolph, B. (2013) Wither urban research? Yes, you read it right first time! Urban Policy and Research, 31(2), pp.130–133.

Randolph, B. (2015) Metropolitan Governance and Planning. Address to the Future of Cities Round- table, Melbourne School of Design, 23 October. Available at: http://blogs.unsw.edu.au/cityfut ures/blog/2015/10/metro-governance-and- planning/.

Stretton, H. (2005) Australia Fair. Sydney: Uni- versity of New South Wales Press.

Taylor, E.J. and Hurley, J. (2015) ‘Not a lot of people read the stuff’: Australian urban research in planning practice. Urban Policy and Research. Published online on 17 February. DOI: 10.1080/08111146.2014.994741.

Troy, P. (2013) Australian urban research and planning. Urban Policy and Research, 31(2), pp. 134–149.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2007) Global Age-friendly Cities: A Guide. Geneva: WHO.