The Post-growth Turn & the Role of Planning

Issue 51(1) of Built Environment, on Post Growth Planning has had in some ways a very long gestation. Some of us were raising concerns about the limitations of ‘growth dependent planning’ as early as 2013, and continue to do so. We can trace growth as a problem rather than a solution for policy makers back to the original Club of Rome Report , ‘The Limits to Growth’ in 1972 while in the UK economists sceptical of growth have been advising government that it is potentially a problem for over 15 years. What distinguishes Yvonne Rydin’s earlier and more recent contributions from the other reports mentioned, is the way the same questions and problems are focused squarely on the practice of planning bringing the problems of growth firmly into the built environment domain.

Although rarely so explicitly, managing the problems of growth has always been a central concern of planning. Plans are key in locational choices for different land uses (e.g.) to ensure rapidly growing cities or an industrial sector doesn’t blight the lives of those living nearby through localised pollution or failing to plan for all the needs of a growing population, not just those that serve the economy. They should be ensuring those in society without power in the market still have access to things like housing, transport infrastructure or spaces for leisure and access to nature, which would never be provided by markets alone even, or especially when they are left to grow unimpeded. Planning has likewise been central to pushing back against the expansion of forms of private transport that sacrifice so much that is valued in the built environment upon the alter of the ceaseless expansion of fossil-fuelled individual mobility.

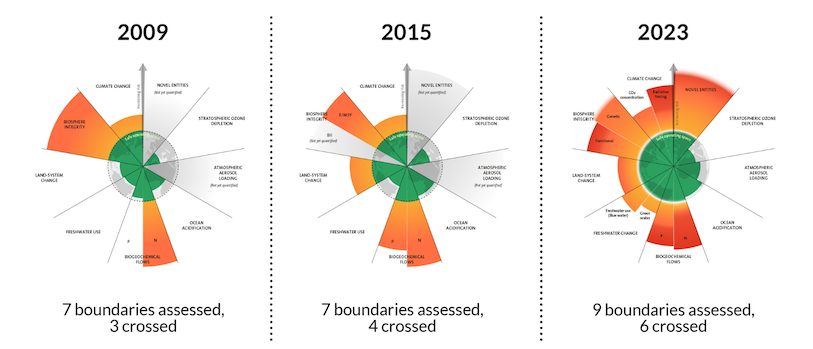

There are two drivers that motivate the authors in this special edition to begin to ask new questions about the built environment, and turn away from manging growth and towards directly challenging it. First, the truly terrifying projections of what the future might hold from climate science. The built environment has always been shaped by disciplines like engineering, architecture, sociology or economics. If we engage seriously with the knowledge from climate scientists, then we need to accept we are crashing through the safe limits in the functioning of multiple earth systems (see figure 1). If, as is likely beyond this point, any of these systems tip over into a less benign state then we stand at the threshold of a very different planet, one where the knowledge that has enabled us as a species to shape the world in our own image must now also reckon with the forces it has unleashed. Whether economic growth is even possible in a world contending with exponentially increasing severity of climate instability is a question that should serve as a wake-up call. More pressing though, given current political insistence of growth as the only strategy for mitigating the severity climate change, is the total lack of evidence that growth represents anything other than more of the same (a negligible reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and the continuing depletion of natural resources).

Figure 1: The evolution of the planetary boundaries framework.

Secondly, a more positive driver of change has been the response to new evidence on climate change and growth. We are proud to be part of a growing movement of thinkers, activists and advocates that are beginning to ask, how do we live well within the limits set by planetary boundaries. The work of economist Kate Raworth on ‘Doughnut Economics’ is just one high profile that readers might be familiar with, not least because it is a framework that a number of cities have explicitly sought to engage with. However, there are many more groups, networks and individuals connecting, sharing information and teaching on Post-growth and Municipal Degrowth. We hope the papers on how the law, the intersection of ethics and economics, municipal water infrastructure and social infrastructure like schools as well as local economies and shrinking cities all contribute in some way to this urgent debate but one in which the contribution of planning remains, as it has always been, a hopeful one.

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

Listing Image/Image 1: The evolution of the planetary boundaries framework. (Source: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. Based on Richardson et al. 2023, Steffen et al. 2015, and Rockström et al. 2009, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html )