Public Space Usage in a Pandemic in Hong Kong

This is the second in a series of pieces about urban public space in Hong Kong from Dr Hee Sun Choi inspired by 43.2 'public space & urban justice' & 44.1 'inclusive design' . The first piece was a pictorial study of the value of urban public space. This second piece is a study of the patterns of behaviour during the pandemic. Here, Dr Choi draws on a review of over 160 small pocket parks in Hong Kong. She focuses on how citizens have changed their behaviour patterns in public space considering Covid-19, and the implications for responding with urban design strategies.

Since the development of contemporary urban design theory in the 1960s, the importance of public space for communal gathering has been a central and vital point. Key theorists Jacobs, Lynch, White, Gehl, Townsend and Bentley have all emphasised the social inclusion and interaction that results from this as a crucial aspect in making our cities more exciting, safe and liveable.

As we all face the challenge and effects to social life and spatial usage brought about to counter the risks of widespread infection from the Covid-19 virus, will this radically change our perspective on this? As Cities prepare for this shifting paradigm, what will be the adjustments made and the alternative choices that are offered, and how will this affect the function and the outlook of urban space and sense of place?

Many scholars, the UN Habitat programme and public observers are already focusing on and raising these important questions, and seeking new ways to avoid virus transmission whilst being inclusive enough to avoid social and psychological exclusion (Florida, 2020; Markusen, 2020; Roberts, 2020, Kissler et al., 2020, Gehl, 2020). Within these arguments there is a new focus on the individual body within the collective, seeking ways to build around the body and take greater advantage of its inherent capabilities, so that people’s enjoyment of the cities can be maintained and enriched by multisensory experience.

This body focus has led to both theoretical debate and design mechanisms that can be seen as construction grids for the creation of socially distanced Vitruvian men or snow angels across the city. With a vaccine currently at large, an unsettling but exciting part of this current public health crisis is that it cannot be known whether these proposals should be read and understood as temporary, ‘pop-up’ strategies for public space, or in fact evolve into a new way of life.

Hong Kong is blessed with a setting and topography that includes beautiful country parks and an extensive network of hiking trails. These are a vital public amenity that have been well protected and preserved despite the massive growth of the city over the last 50 years. However, they are not easily accessible to all, with an average journey time of 1 hour and travel cost required that end up to be discouraging factors for some. In addition to these amenities, there are a large number of city parks, squares and small pocket parks within the city, that offer a more accessible opportunity for outdoor rest and recreation. However, most have in place either active or passive deterrents to discourage people to properly relax and engage with the natural environment there. Most of the users are not allowed to get close to or touch the plants in the public parks, and if there is a fountain in a public space, the side is slanted so people cannot sit comfortably (Hendrick, 2020).

Given its density and housing costs, with many Hong Kongers living in very limited spaced due to soaring property prices, these local outdoor spaces provide an important outlet for local residents to stretch their legs. With the alternative, indoor environments for rest and relaxation- restaurants, shopping malls, social clubs, either closed or at an heightened risk of virus transmission, these outdoor spaces become all the more important. Cities around the world have introduced changes to public space policy and usage in various ways, with Lithuania’s capital Vilnius permitting bars and cafes access to public spaces to allow safer forms of social interaction with social distance. San Francisco authorities have closed certain roads to vehicles to allow residents to run, bike and walk safely, and US cemeteries are seeing a surge in visitors seeking some outdoor space.

What has been Hong Kong’s response? How have the arrangements and usage of public space evolved in relation to Covid-19?

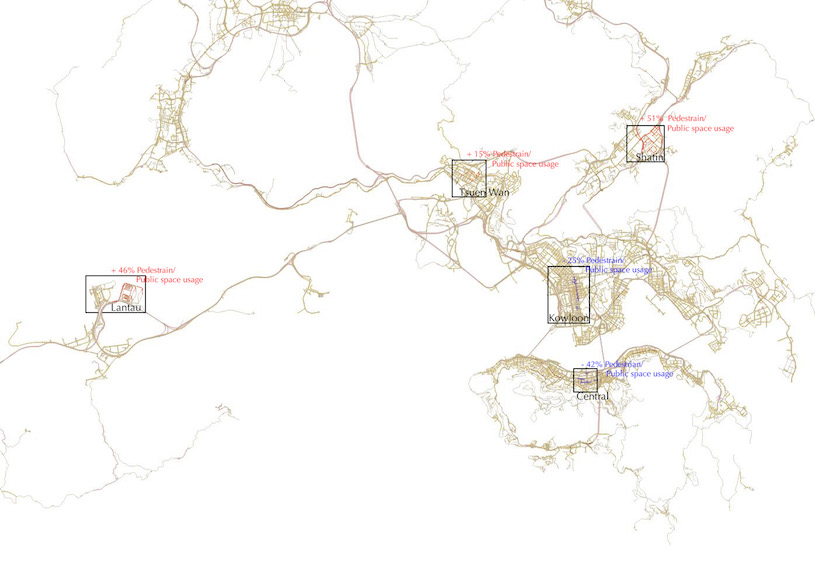

This can be challenging in a dense city, and particularly a commercially driven city like Hong Kong, with limited public space. Especially when people are required to stay very close to their homes, or to avoid public transport to reduce the risk of spreading the virus, it could reduce their access to Hong Kong’s larger green and blue spaces (McCay, 2020). However, Hong Kong’s government have not yet adapted with proposals of the likes of Vilnius and San Francisco, and decision makers and designers have not yet been tasked with this. Within a crisis such as this there lies an opportunity not just for ‘pop-up’ responses and quick fixes, but also longer-term design strategies. For example, business and workplace strategists are predicting that it will reduce business overheads and increase productivity in a number of sectors if a proportion of the workforce continue to work from home for at least a part of their working week. How will this affect the usage of public space throughout the day and across the commercial and residential areas of the city?

Figure 1: Hong Kong Central Line and flows of people (click to enlarge image).

Considering that we are now in March, 2021 and facing a 4th wave of Covid-19 in Hong Kong, a study was made including observational across the different public realms and neighbourhood of Hong Kong. In general, people are either avoiding or not allowed to use public gardens, playgrounds, basketball grounds and the like. Consequently, the general usage of pedestrian walkways and informal public space between buildings and waterfront promenades has increased, and these spaces have become busier and more popular. People still clearly yearn for social gatherings in bars, restaurants and in festivals costumes. But with restrictions in traditional venues and public spaces, those spontaneous behaviours are spreading within institutes, companies, and neighbourhoods.

Figure 2: West Kowloon Art Park:

It has become popular for people bring their own chairs, tents and food to spend their weekend in this public park. Before Covid-19, this kind of usage and behaviour pattern was rare within the public spaces of Hong Kong.

According to the observation and findings, changes in behavioural patterns in public space and temporary design strategies in Hong Kong in response to Covid-19 can be categorized in three ways:

1. Personal Costumes

2. Public guidance for public usage

3. Architectural design choices for social life

Each aspect of the personal costumes, public guidance, and architectural design choices for social life, as illustrated below (click to enlarge image).

Figure 3: Patterns & temporary design strategies.

A necessary requirement for these mechanisms to function is that the density of occupation would need to be more carefully controlled than before, requiring a much greater degree of access control, especially the high dense city like Hong Kong. With this comes a limitation in the freedom of usage for public space, this public usage is also a test of faith and capability for the urban community to collectively care for and respect each other in a way that can balance this concern for safety and distance whilst finding enjoyment and physical well being in the open air.

My findings from the site observations are that currently most of users are seeking to create privacy with social shielding, rather than adapt to the limitation in freedom of well-designed public spaces. As cities across the world look for safe, socially distanced ways to exercise, socialise, work and play, we become aware that these spaces are more vital than ever before. Putting these amenities at the heart and soul of a city is about far more than aesthetics. It should be about community, participation and connection.

References

Florida, R. (2020). We’ll need to reopen our cities. But not without making changes. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-27/how-to-adapt-cities-to-reopen-amid-coronavirus

Gehl, J. (2020), Public Space & Public Life during COVID-19, Copenhagen, Kobenhavins commune.

Hendrik, T. (2020), Hong Kong’s public space problem, cited by Chermaine Lee, 2 September 2020, BBC Worklife, https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200831-hong-kong-public-space-problem-social-distance

Kissler, S.M., et al. (2020). Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. doi:10.1126/science.abb5793

Lee, C. (2020), Hong Kong’s public space problem, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200831-hong-kong-public-space-problem-social-distance

Markusen, A. (2020). Will COVID-19 drive us farther apart, or bring us together? Will we all move away from each other? Not likely. https://minnesotareformer.com/2020/04/07/will-covid-19-virus-drive-us-farther-apart-or-bring-us-together/

McCay, L., (2020), Hong Kong’s public space problem, cited by Chermaine Lee, 2 September 2020, BBC Worklife, https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20200831-hong-kong-public-space-problem-social-distance

Roberts, D. (2020). How to make a city livable during lockdown. Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/cities-and-urbanism

UN-Habitat (2020). UN- habitat key message on COVID-19 and Public Space, May, 2020, United Nations Human Settlements Programme, www.unhabitat.org

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

All Images © author. All rights reserved.