The nuances of sociability

Jamin Creed Rowan’s book The Sociable City: An American Intellectual Tradition (2017) is an interesting and enlightening read on urbanism which sets out to widen the discourse of sociability through variety of new sources. Alongside the professional discourses of planning and urban design professionals, for decades now there has been ongoing discussions that has not generally been acknowledged or referred to. Rowan pin points how the resource of materials from memoirs, plays, novels and literary journalism, and museum exhibits have been overlooked in the more established history of urban life. Through this set of source material Rowan introduces the discussions of approaches to sociability, so that it starts to make sense to urban history, and creates a new and logical line of thinking which has not previously been considered in the evolution of urban development in the North American context. According to Rowan, urbanist and historians have filtered the quality of social interactions into oversimplified categories which overlook essential points of sociability. In doing so, the understanding of cities and their capacities to evoke all kinds of interrelations between people, places, materials and ideas can be missed. The book illuminates the very nuanced and enriched intellectual and cultural history within US urban thought that also promotes more nuanced understanding of city development. Rowan argues that the way society defines interpersonal affection defines what kind of cities we create.

Image 1: Mulberry Street NYC ca.1900

Rowan maps the understanding of sociability through the concept of fellow-feeling. He tracks the roots of sociability and fellow-feeling to Frederick Law Olmsted’s understanding of sympathy between urbanites. By the mid-nineteenth century the concept of sympathy had become the social ideal for most Americans, in relation to how the interactions and relationships were evaluated, which was closely informed by moral philosophers such as Adam Smith, Archibald Alison and Hugh Blair according to Rowan. What Olmsted was saying was that the city dramatically changes the way people interact and feel to each other. Like Olmsted many urbanists of the time were worried that the early industrial city with heavy migration, economic volatility, cultural chasms, and the compact urban form, could cause negative side effects unless mutual sympathy was promoted in planning of cities. Olmsted’s recipe was to create public sphere as parks, like central park in New York, in which people could shut out the city and its congested streets, and engage with other people in peace in order to establish familial feeling towards each other. Rowan points out, however, that Olmsted’s understanding of sympathy came very close to understanding of private domestic spaces and the intimacy of primary relationships like between family members.

Rowan points out how early twentieth-century urban sociology reduced the relational forms into two categories namely primary (superior) and secondary (inferior) relationships. Rowan argues that while the contemporary interpretations were more connected to the degree of affiliations and created a sense of community, more sophisticated modes of thinking about urban sociability were needed in order to build and manage cities in a better way and facilitate all kinds of fulfilling social networks and relationships. In doing so Rowan emphasizes capturing and validating the less intimate and more casual interactions and fellow-feeling that connects the urban inhabitants to each other and promote a wide variety of interactions.

You read this book like a detective story - what happens next. Even though the context of urban design development in America is fairly well known, for most readers the urban sociology line of inquiry in the book is unlikely to be familiar. This makes you want to read more to understand ‘who did it and why’. In the end, the threads of the story lead to Jane Jacobs (as indicated in the introduction) and throughout the book her work gradually appears as a logical culmination point from a longer line of thinking from the nineteenth-century. This helps to understand where Jacobs' thinking springs from and some less well known dimensions of her work.

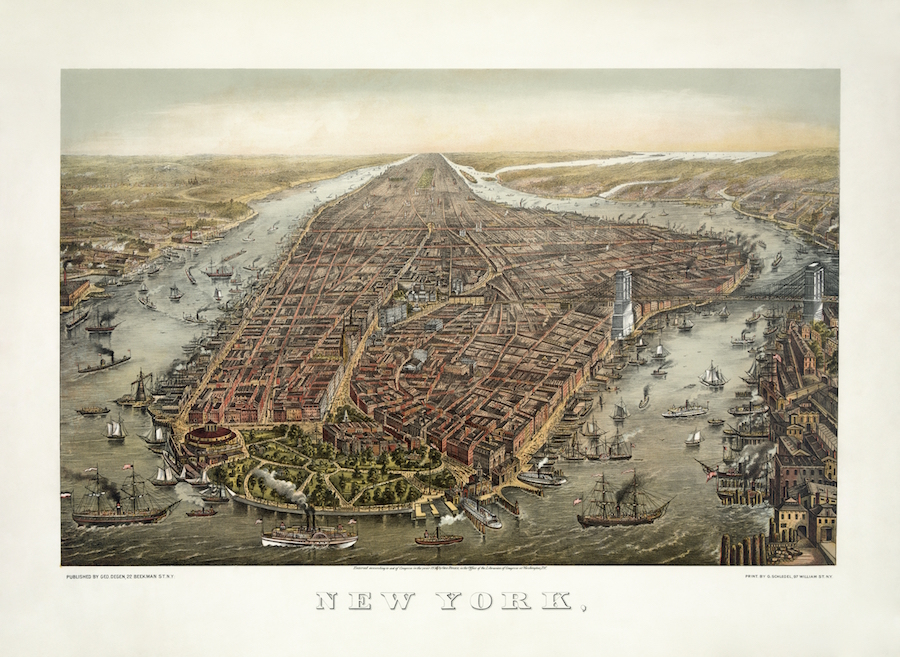

Image 2: Manhattan panorama 1873

Rowan starts his journey from the Settlement Movement in North America at the end of the nineteenth-century. He continues to New Deal Urbanism in the interwar era and all the way through to the postwar city and the consolidation of the understanding of urban sociability at that time. The Settlement Movement started to widen the understanding and dynamics of familial-feeling also comprising variety of relationships other than primary relationships that were founded on emotional intimacy. The Settlement Movement produced new kinds of communal spaces for people who were not necessarily living together. By contrast, the social interwar public housing projects reflecting the new deal politics were an attempt to focus again on the primary relationships that were promoted heavily in urban planning of social housing developments like in Brooklyn the area called Williamsburg (Williamsburg houses) that replaced the old city block structure of very poorly managed housing. Rowan’s research on variety of resources such as the book by Betty Smith A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943) and the several writings of New Yorker journalists since 1930s, such as E. B. White, Meyer Berger, Joseph Mitchell, A. J Liebling, Alva Johnston, Niven Busch, Jr., and St. Clair McKelway portrayed a totally different set of sociability that relied on more secondary relationships but that were essential for the wellbeing of the society and city dwellers. While the planners of Williamsburg advocated sunshine, air and greenery according to best modernist design concepts inherited from functionalism, Smith brought to surface in her fictional book (however, portraying Williamsburg) a totally different view on the area, which had domesticated its streets and sidewalks as a form of social control. Smith referred to social injustices that the new city structure produced by excluding people, like the character of single mother Joanna with her baby depicted in the book. The commercial and service infrastructure that vanished from the area by building the new Williamsburg estate had brought together a very varied set of people, producing diverse ways of being and interacting, and creating a sense of inclusion, which promoted fellow feeling between people even though they had not necessarily verbally interacted.

Image 3: Highline Phase2

In his book, Rowan portrays clearly with several examples how the physical and emotional wellbeing depends of wide variety of urbanites that makes their life in the city possible. He also draws attention to the importance of the discipline of ecology evolving in the post war period, and the ecologically minded writers and urbanists that emerged as a consequence. Those writers further validated the importance of interconnectedness of urbanites that were not necessarily familiar to each other but who shared the same urban environment and were different ways connected and important to each other. This was a discourse popularized by Rachel Carson in the New Yorker magazine. Ecological thinking offered a new viewpoint on the city, which challenged the urban renewal projects that were disrupting its social orders and upset a multitude of fragile relationships from human to natural habitat in built environment. It was based on the notion that everything is fundamentally connected.

The next logical step in Rowan’s line of argument was Jane Jacob’s writings that brought all thinking on sociability together. Rowan writes, “Those who valued the city’s more informal and often invisible social networks insisted that preserving and creating a physically diverse built environment would be critical if the city were to sustain the somewhat less emotionally intense fellow-feelings capable of binding an increasingly diverse population of city dwellers to one another” (2017, 13). Rowan argues how the publication of The death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs (1961) signaled a consolidation of the urbanist discourse of sociability. According to Rowan Jacobs' book brought together range of disciplinary perspectives, cultural forms, narrative conventions that constituted the urbanist discourse of sociability that helped to acknowledge and maintain the infinite number of casual affiliations that make the city life.

Rowan sees that the future of the development of urban sociability lies in the ability to recognize urbanist discourse, which is continually evolving, in order not to dismiss the emerging configurations of affiliations in today’s cities as city dwellers develop new forms of communications. Rowan reminds us to be very perceptive in all kinds of 'voices' and sources because how we listen and define them, the way we create our physical built environment. The tour that Rowan takes the reader through, in defining the less visible nuances of urban sociability, is also very entertaining and supported by interesting stories and observations without ever losing the thread of the question at hand.

Jacobs, J (1961) The death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Smith, B (1943) A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. New York: Harper & Borthers.

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme!

Listing Image/Image 1: Mulberry Street NYC ca.1900 (Source: United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2972458)

Image 2: Bird's-eye panoramic view of Manhattan 1873, looking north with Battery Park in the foreground and the Brooklyn Bridge on the right. (Source: United States Library of Congress's Prints and Photographs division, Lithograph restored by Adam Cuerden, Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_New_York_City#/media/File:George_Schlegel_-_George_Degen_-_New_York_1873.jpg)

Image 3: Highline Phase2 (Source: Eric Wittman via Flikr, CC BY-ND 2.0, https://www.flickr.com/photos/ricoslounge/7046330899)