An engine for ‘The Power of Plans’

Wray and Natarajan’s editorial for issue 48(4) is a ‘pathology’ on the power of plans and what makes them successful. It triggered a lot of memories and reflections from my career. However, I missed the critical time when planning started going into retreat after the ‘79 election because I worked in Hong Kong between 1978 and 1988. Out in Hong Kong the mantra ‘public is bad, private is good’ was never heard. And, for a place which was very much publicly led, the private sector, not to mention the economy, did very well.

My blog is in part based on a worms’ eye view from the time I entered the planning profession in the 60s. Over time I recognised that plans are key to facilitating development, including the quality of development, because they help marshal resources and guide development and inform investment. As Churchill said, ‘He who fails to plan, is planning to fail.’

Figure 1: Hong Kong Central Close Up from the Peak

Powerful Plans as Tri-Structures

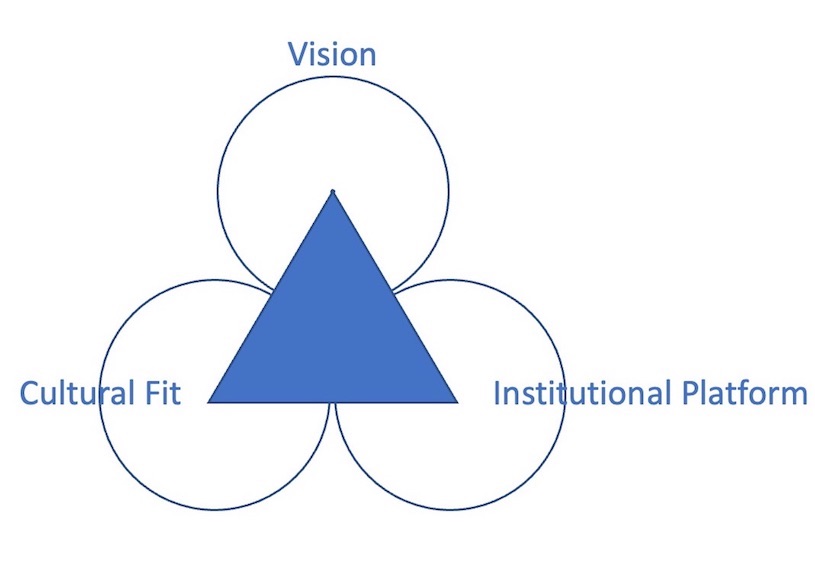

The conclusions of the editorial with respect to Powerful Plans as Tri-Structures (figure 2) make a lot of sense in diagnostic terms in terms of Vision, Institutional Platform and Cultural fit. However, in my experience, the approach outlined wouldn’t necessarily lead to a ‘cure’ because of the need to focus on political will and resources.

Figure 2: Powerful Plans as Tri-Structures

In Sir Kenneth Calman’s autobiography (Calman, 2019), when reflecting on his experience as Chief Medical Officer for England and Wales, he realised how much of his experience in the successful delivery of change resonated with Clausewitz’s findings from his treatise ‘On War’. Calman calls on the notion that, ‘no battle plan ever survives first contact with the enemy’[1]. In particular, he paraphrased four things which need to be in place for victory:

1. political will;

2. a clear strategy;

3. people on the ground with the skills and authority to make decisions; and

4. an effective supply line of adequate resources, including people, skills, and finance

All these factors appear in the editorial – that synthesises an international collection of seven studies of plans - the difference lying merely in the terms used. However, an engine to drive things forward is also required.

It is evident from the editorial that the UK’s long-term failure in the provision of infrastructure, land for housing, and much needed regeneration and development, arises from successive governments failing to observe Clausewitz’s four principles. This has impacted on housing, business and transport, and it has affected economic growth and employment. As a consequence, for over a decade I have nurtured a dream. I would like to see is new legislation which reimagines the New Towns Act in a standalone way, i.e. as an engine to deliver change. It would be transformative to have the powers and resources of the original Act to use within and around existing settlements available to deliver land for housing, upgrade infrastructure and facilitate the regeneration of our ailing town and city centres. The content of such legislation needs requires a conversation. Here, I am pleased to say, Wray and Natarajan’s editorial and the authors of the case studies provide an excellent starter for 10!

Planning in Retreat

Post war planning strategy in the UK and Europe was largely monocultural, i.e. housing-led. Housing conditions in 1945 were terrible in all major UK industrial cities. Arguably in these times a ‘Vision’ wasn’t required because we were living in the ‘problem’. Housing was a natural priority for the post war Government, as recounted in Murphy’s Rebuilding Britain (1970).

Probably the top-down approach after the war was an unconscious continuation of war time practices lacking public consultation exercises. At this time, the 90% grant allied to designated Comprehensive Development Areas, in contrast to modest housing improvement grants, created a mindset for a demolish and new build strategy. This was even where stock was structurally sound but deficient in running water and bathrooms. This ‘culture’ also suited the construction industry because the rehabilitation of houses, like brownfield sites, involve more risk, are more complex to implement and require more costly tradesmen. Anyway, the ‘success’ of the post war housing strategy meant people did enjoy much better quality housing whether in peripheral housing estates, New Towns, or even nearby settlements through overspill.

As a planner I am often frustrated, even angry, to hear politicians blame planners for the housing shortage amongst many other things. The irony is with the arrival of market-based politics, i.e. that the market will provide society’s needs, one bit of the planning system is seen to work, i.e. ‘development management’. This has been hijacked by the NIMBYs. A potent force which has undermined the strategic, and visionary, role of planning.

Figure 3: Liverpool city centre

In Defence of the Capable State

Wray and Natarajan capture the Wake-Up Call message of Economist writers John Micklethwaite and Adrian Woodridge (2020), who recognised the importance and power of the state - after years of being scourges of the big state and proponents of globalisation. However, I think that the jury still has to be out on Gerstle’s (2022) conclusion that Neoliberalism has run its course and fading rapidly. I am reminded of Pope Augustine’s lament “Lord, give me chastity and continence, but not yet!”.

Figure 4: Transport in central Dublin

Concluding reflections

The Power of Plans studies reveal that the engines for change in the seven cases examined, were exogenous. In those of Liverpool (figure 3) and Dublin (figure 4), it was the EU that brought the political will, the resources and the single mindedness to deliver change. It also, through partnerships, brought diversity into the planning process and an opportunity to give stakeholders ownership of strategies. Importantly, the decisive role of public sector in the cases studied helped incentivise, reward and de-risk private sector investment. Implicit in de-risking is gaining stakeholder trust and confidence which turbocharges investment. Less emphasised but evident, is the importance of placed-based power and decision taking. Here a recent book by Robin Hambleton Cities and Communities Beyond Covid-19 (2020) offers interesting new insights to a form of governance to better lead the recovery from Covid.

Hambleton’s proposed new civic leadership approach is based on ‘power of place’, and thinking ‘civic’ rather than public. It has a focus on ‘leadership’ and a participatory stakeholder approach. Because the word ‘public’ has become toxic in political debates (see for instance, Finkel et al., 2020) and when issues in our cities and communities are being addressed, ‘civic’ is better. Hambleton says our places need to take advantage of ‘place-based’ leadership in five local ‘realms’; i.e. political, professional (public and private), business, community and trade union. His view is that place-less national and international power has been the source of most of our problems.

So, there you have it, a whole range of ideas on how to deliver successful change through the Power of Plans. Here I return to the idea of an ‘engine’ and a re-imagining of the New Town Act. An act, say, to create regional partnerships to deliver land for housing, to enable upgrading of infrastructure and facilitating the regeneration of our ailing town and city centres within our existing towns’ and cities’ boundaries, maybe even help us move towards Zero Carbon. It would be a piece of legislation which puts an ‘engine’ into the Power of Plans. This is something which has been neglected in our Planning System for decades. Here Wray and Natarajan’s editorial is inspirational.

References

Calman, K. (2019) It started in a cupboard, Adventures in Life, Learning and Happiness. Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Finkel, E.J., Bail, C.A., Cikara, M., Ditto, P.H., Iyengar, S., Klar, S., Mason, L., McGrath, M.C., Nyhan, B., Rand, D.G. and Skitka, L.J. (2020). Political sectarianism in America. Science, 370(6516), 533-536.

Gerstle, G. (2022). The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hambleton, R. (2020). Cities and Communities Beyond Covid-19. Bristol University Press 2020.

Micklethwait, J., & Wooldridge, A. (2020). The Wake-Up Call: Why the pandemic has exposed the weakness of the West-and how to fix it. Hachette UK.

Murphy, L. R. (1970). Rebuilding Britain: The Government's Role in Housing and Town Planning, . 1945-57. The Historian, 32(3), 410-427.

von Clausewitz, C. (1976) On war. Princeton University Press.

________________________________________________________________

As ever we welcome further Built Environment blogs & tweets on this theme.

Listing Image/Image 1: Hong Kong Central Close Up from the Peak (Source: Author)

Image 2: Powerful Plans as Tri-structures (Source: Wray & Natarajan)

Image 3: Liverpool city centre. (Source: Parkinson; Photo: CC livingOS)

Image 4: Dublin tram. (Source: Mangan et al.; Photo: CC William Murphy)

[1] Widely attributed to the 19th century Prussian general von Moltke, and neatly expressing Clausewitz’s seminal treatise.