Editorial: Impacts of HSR: Hubs, Linkages, and Development

About this issue

Summary

In 1993, Built Environment (Volume 19, No. 3/4) introduced ‘The Age of the Train’; twenty years later, there was a follow-up issue: ‘High-Speed Rail: Shrinking Spaces, Shaping Places’ (Volume 39, No. 3). Now, in 2020 this issue With case studies from China, Spain, France, the Netherlands and the UK, contributors to this issue examine the social, spatial and economic impacts of HSR at different scales and different stages of development in different parts of the world.

Impacts of High-Speed Rail: Hubs, Linkages, and Development

CHIA-LIN CHEN and ROBIN HICKMAN

We are living in a highly-connected and mobile world, built on technology-driven development, with complex interactions between technology, society and space (Castells, 1996). High-speed rail (HSR) is associated with time–space shrinkage through faster links between cities. Since its first appearance, the HSR network has continued to grow and extend, both at national and international levels – a new technology that helps to reshape the world. In February 2020, the global network operation reached over 50,000 km, three-quarters of which is located in Asia-Pacific, and mainly in China.

The anticipated impact of HSR has been much debated. Research interest in the wider developmental impact of HSR can be traced back to the early 1990s and has, since then, been a contentious subject for discussion. In 1993, a special issue entitled ‘The Age of the Train’ (Volume 19, No. 3/4) was published in Built Environment and, twenty years later, a follow-up special issue was entitled ‘High-Speed Rail: Shrinking Spaces, Shaping Places’ (Volume 39, No. 3). Although HSR has often been regarded as a key national policy, the ways in which it has been embraced and implemented – given differing geographical scales, economic trajectories, cultural and political systems – varies markedly from one country to another. Indeed the research approach to studying impacts varies according to contexts and can lead to different interpretations of the topic. Over the past thirty years, research has shown mixed results, acknowledging that the wider impacts are not automatic and universal, but that the context is indeed everything:

HSR alone cannot explain the variations between places fully … successful adaption, however, depends on the existence of supporting policy measures, such as innovative funding, devolved planning power, institutional leadership and coordinated governance at different spatial levels. (Chen et al., 2019, p. 12)

The existing literature on the wider impacts of HSR can be developed in many ways, but we consider three areas in this special issue. First, most research focuses on places and spatial-economic changes, taking freedom of movement – including capital, talents and business – for granted. There is little research looking into human-centred impact, such as inter-city HSR commuting practice across a region. Second, evidence has largely been drawn from econometric modelling, such as ex-post (after the fact) regression analysis at aggregate levels. It fails to examine the disaggregate level, such as explanations for the location and layout of stations, why impacts vary between places, and the way HSR opportunities have been exploited at multiple and interrelated levels, from station-area development and urban regeneration to wider regional development. Third, impact assessment has been short-term, failing to reflect the nature of transformative effects that require long-term study involving complex interactions of a myriad of factors. Even edited collections of papers across the range of research are scarce.

In this issue of Built Environment, we address these points by offering an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon of HSR and impact, considering case studies at multiple scales, with different developmental stages, political systems and in varied parts of the world.

Case studies are drawn from China, Spain, France, the Netherlands and the UK. The seven papers cover the following themes:

- Inter-city HSR commuting phenomena;

- Interchange experiences in an HSR station;

- Spatial evolution with and between urban agglomerations;

- Impacts of HSR: hubs, linkages and surrounding development;

- Good station-area planning;

- Urban development around HSR stations;

- Intra-regional rail network improvement for rebalancing effects of HSR investment.

The first two papers look at travel into and out of HSR hubs from human-centred perspectives, both at urban and station levels. Chung et al. (2020) explore the inter-city HSR commuting phenomena – how commuting time is associated with the built environment around workplace and residence, travel modes to and from HSR stations, and commuting frequency (daily or weekly). This is analysed from a door-to-door journey perspective, considering new job prospects created when two cities are linked by HSR. This fills a gap in the existing literature, which emphasizes the time saving between HSR hubs while ignoring the total journey time involved when including necessary travel to and from HSR stations. The findings show that commuting time is closely associated with travel modes and commute frequency, but no association is found concerning density of public transport facilities. Surprisingly, public transport modes, such as the metro, show statistical significance, revealing increased commuting time in both access and egress trips, while walking from HSR stations to the workplace is associated with a significant reduction in commuting time. Moreover, daily commuting is associated with shorter access trips, while weekly commuting is related to longer egress times. The differences identified between home and workplace cities can be attributed to the varying functions and scale of the cities.

Bo Wang et al. (2020) examine a newly-opened HSR station in Hong Kong, considering the intermodal integration of HSR with the local public transport systems. They use a survey with passengers arriving at the station concerning their interchange experiences. Objective and subjective measurements are examined. The attributes of services, including instrumental and affective dimensions, are found to have significant influence on the interchange experience. The results show a generally positive experience, while significant differences are found between different modes. The findings also identify both good and unsatisfactory services that require urgent improvement or maintenance. Tin the case of those needing urgent improvements it is mainly to instrumental factors, including ticket purchase, time coordination and interchange signage, while good services include walking environment cleanliness, congestion-free waiting areas and luggage delivery.

Chunyang Wang (2020) examines the impact of individual HSR hubs at a larger scale, evaluating the impacts of HSR on spatial-economic changes in urban agglomerations in China. The paper analyses different economic trajectories within five major urban agglomerations and between urban agglomerations at the national level. The first part of the analysis, measuring population and economic changes by difference-in-difference (DID) methods, shows that spatial inequalities between HSR and non-HSR cities have been reduced in advanced Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta urban agglomerations, but widened in less advanced ones such as the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River and Chengdu-Chongqing. Second, the findings illustrate the way HSR connectivity has given cities varied levels of centrality and reinforced the role of hub cities on the network. A dependency index reflects the stronger connectivity between key centres in different urban agglomerations rather than within agglomerations. The centrality measures emphasize the greater concentration of links between the three largest cities – Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou – on the national scale. The two analyses highlight that HSR may result in either concentration or diffusion of development within urban agglomerations, depending on the developmental trajectories and particular context. In the more advanced urban agglomerations, where pre-HSR economic and infrastructure links have been extensively developed, the arrival of HSR tends to show more balanced development opportunities for both HSR and non-HSR cities. In less developed urban agglomerations, with under-developed infrastructure and economies, the arrival of HSR appears to lead to concentration of resources for those HSR cities rather than non-HSR cities.

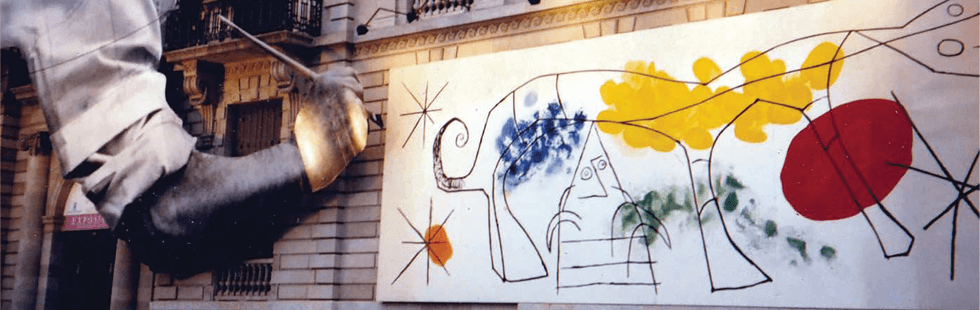

Using a photo essay, Hickman and Chen (2020) illustrate the key features and lessons of HSR experiences in China using three inter-related themes: hubs, linkages and surrounding development. The paper examines HSR interchanges in major cities, which are designed as large-scale, modern and often spectacular interchange hubs with multiple modes. Inside a HSR hub complex, the spatial arrangement is similar to a modern airport terminal, where check-in, departure and arrival levels, shopping and waiting spaces are placed on different levels to manage large volumes of passengers at peak times. Outside a hub, many HSR station edge locations pose challenges for accessibility of the first and last mile, especially for those inter-city HSR commuters who seek better job prospects after the arrival of inter-city HSR services. Finally, the paper highlights how HSR is used by both national and local government as a strategic development tool, catering for rapid urbanization and integration of urban agglomerations at the regional scale.

To consider the experience of HSR over a longer period of time, the following three papers focus on developments in Europe from the 1980s onwards. Loukaitou-Sideris and Peters (2020) examine the key elements and prerequisites for good station-area planning, using four case studies of successful European stations: Euralille, Lyon Part-Dieu, Rotterdam Centraal and Utrecht Centraal. This aims to generate lessons and recommendations for future new HSR station development. The paper illustrates key elements for good station-area planning: ‘attention to context’; ‘balance of the dual nature of station and station-area’; ‘land use coordination’; ‘quality of place’; and ‘accessibility through increased intermodality’. Good station-area planning should be characterized by three types of connectivity; namely, spatial, intermodal, and operational (here referring to the planning governance among stakeholders). The paper concludes that the transformative effects of HSR could be achieved more easily with careful planning and integrated station-area urban design.

Examining Spanish case studies, Ribalaygua et al. (2020) offer a comprehensive examination of the evolution and effectiveness of urban development around high-speed rail stations. They identify three major groups of factors that are commonly considered in studies of urban development around HSR stations, namely: spatial structure (population, density and nodal connectivity); socio-economic context (projects and development; real-estate market evolution); and local actions (planning decisions, functional strategies and governance strategies). These factors are assessed through the complex implementation process, including initial development and redevelopment. Six selected case studies include two central stations (Córdoba, Valladolid), two central-edge stations (Ciudad Real and Zaragoza), and two peripheral stations (Guadalajara and Tarragona). The combination of comparative analysis with detailed case studies enables examination of the possible connection between HSR opportunities and realized urban development. The findings show that the socio-economic situation is the strongest determining factor for development in the short term, while all the case studies experience a positive developmental impact associated with the announcement of a HSR station location. There is a key role played by HSR in long-term urban development. The conclusion is that HSR is a good catalyst for urban development, but that local conditions and actions are crucial for harnessing its potential.

The final paper comes from the UK, which lags behind other countries in constructing a new HSR network. High-Speed Two (HS2), the major transport infrastructure proposal over the past decade, remains an ongoing controversy. Wray et al. (2020) examine high-speed services for Northern England and explore how high-quality and efficient east–west rail linkages across Northern England could be delivered. They argue that HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail (effectively HS3 for the North) can be critical to regional development. The paper revisits ‘the Hall Plan’, proposed by the late Sir Professor Peter Hall, setting out a vision for high-speed rail connections between Liverpool–Manchester–Leeds–Sheffield–Hull over twenty years, linked to HS2, and realized by a pragmatic incrementalism in five stages. The key message is that there should be no delay in the improvement of regional connectivity. In view of poor mechanisms for strategic planning in the UK, indecision, scepticism of long-term planning, over-centralized financial control via the Treasury, and fragmentation of the rail industry, the paper highlights the importance of implementation via a combination of new construction sections, electrification and progressive upgrades.

A wide-ranging approach to exploring the inter-relations of HSR hub, linkage and development on different scales is illustrated in the papers in this issue. Three key messages are distilled. First, experiences from other countries can be inspirational, despite different styles of infrastructure investment and planning cultures. We can learn much from successful HSR rail implementation in other contexts. For instance, Sideris and Peters (2020) draw on Rotterdam Centraal HSR station to suggest, ‘if planned at the right scale, even a very high volume HSR station does not need to overwhelm or destroy the quaint character of the adjacent resident neighbourhoods’. This could be relevant to Chinese HSR stations and the interchange experiences, including pedestrian and cycling access, integration with other transport options and urban fabric. Chinese development approaches demonstrate a strong commitment to urbanization, infrastructure investment, speed of implementation, as well as the inexpensive pricing of travel. These are all important lessons for the UK in considering the design of HS2 and HS3. Second, no formula is fit for all contexts and guaranteed to have positive impacts, as development is context-specific and dynamic. The planning systems is, of course, critical to the development that surrounds the HSR station and the linking of cities across the region. But often this seems to be overlooked and it is assumed that infrastructure investment will naturally lead to positive development change. Third, a long-term and proactive development process is required for achieving transformative effects of HSR, in particular for new interventions. This also reflects the issue of path dependency; as Ribalaygua et al. (2020) remark, ‘HSR can strengthen existing tendencies or potentials, while it is much weaker when launching new urban spatial processes’.

In conclusion, the technological advance of high-speed rail can shape our cities and lives, depending on the way HSR is embraced, planned, and implemented in different contexts. Much more consideration and research should be focused on understanding the social changes brought about by infrastructure investment, supporting measures, territorial opportunities and challenges – it is important to make the most of large investments. The developmental impacts of HSR investment is not automatic and guaranteed, but depends on a myriad of factors, including urban planning approaches at strategic and local scales. Integrated urban planning and transport investment can help develop stations as part of new urban neighbourhoods and as part of a wider metropolitan region. This includes supporting urban public transport systems linking into the main HSR networks (Hickman and Osborne, 2017). A wide-ranging perspective embracing HSR hubs, linkages and surrounding development is important for attaining a fuller picture of the complexity of HSR and its potential. Future HSR research should encourage examination of more in-depth case studies across different contexts, so that we can learn more about the most effective designs and associated urban dynamics.

REFERENCES

- Castells, M. (1996) The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Chen, C.-L., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Ureña, J.M. and Vickerman, R. (2019) Spatial short and long-term implications and planning challenges of high-speed rail: a literature review framework for the special issue. European Planning Studies, 27(3), pp. 415–433.

- Chung, H., Yang, Y., Chen, C.-L. and Vickerman, R. (2020) Exploring the association of the built environment, accessibility and commute frequency with the travel times of high-speed rail commuters: evidence from China. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 342–361.

- Hickman, R. and Osborne, C. (2017) Sintropher Executive Summary, Interreg IVB. London: UCL.

- Hickman, R. and Chen, C.-L. (2020) Impacts of HSR in China: a Photo essay. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 398–421.

- Loukaitou-Sideris, A. and Peters, D. (2020) What is good station-area planning? Lessons from experts and case studies. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 422–439.

- Ribalaygua, C., García, F. and Ureña, J.M. (2020) Urban development around Spanish high-speed rail stations: plans, realized development and lessons. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 440–465.

- Wang, B., Loo, B.P.Y. and Li, L. (2020) Situating high-speed railway stations within local urban contexts: passenger satisfaction with intermodal integration at the Hong Kong HSR station. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 362–378.

- Wang, C. (2020) The Impact of high-speed rail on the spatial sructure of Chinese urban agglomerations. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 379–397.

- Wray, I., Thrower, D. and Steer, J. (2020) High speed rail in Northern England: tactics and policies for implementing mega plans by modular incrementalism. Built Environment, 46(3), pp. 466–484.

Impacts of HSR: Hubs, Linkages, and Development

About this issue

Summary

In 1993, Built Environment (Volume 19, No. 3/4) introduced ‘The Age of the Train’. This was followed in 2009 by ‘Railways in Europe: A New Era’ (Volume 35, No. 1), then in 2012 by ‘Railway Station Megaprojects and the Re-Making of Inner Cities in Europe’ (Volume 38, No 1), and the following year by ‘High-Speed Rail: Shrinking Spaces, Shaping Places’ (Volume 39, No. 3). Now, with case studies from China, Spain, France, the Netherlands and the UK, contributors to this issue examine the social, spatial and economic impacts of HSR at different scales and different stages of development in different parts of the world.

Contents

-

Impacts of High-Speed Rail: Hubs, Linkages, and Development

CHIA-LIN CHEN and ROBIN HICKMAN -

Exploring the Association of the Built Environment, Accessibility and Commute Frequency with Travel Times of High-Speed Rail Commuters: Evidence from China

HYUNGCHUL CHUNG, YUEMING YANG, CHIA-LIN CHEN and ROGER VICKERMAN -

Situating High-Speed Railway Stations within Local Urban Contexts: Passenger Satisfaction with Intermodal Integration at the Hong Kong HSR Station

BO WANG, BECKY P.Y. LOO and LU LI -

The Impact of High-Speed Rail on the Spatial Structure of Chinese Urban Agglomerations

CHUNYANG WANG -

Impacts of HSR in China: A Photo Essay

ROBIN HICKMAN and CHIA-LIN CHEN -

What is Good Station-Area Planning? Lessons from Experts and Case Studies

ANASTASIA LOUKAITOU-SIDERIS and DEIKE PETERS -

Urban Development around Spanish High-Speed Rail Stations: Plans, Realized Development and Lessons

CECILIA RIBALAYGUA, FRANCISCO GARCÍA SÁNCHEZ and JOSÉ M. DE UREÑA -

High Speed Rail in Northern England: Tactics and Policies for Implementing Mega Plans by Modular Incrementalism

IAN WRAY, DAVID THROWER and JIM STEER

Publication Reviews:

- Cover image: Panorama of Tianjin West Station. (Photo: CC kele_jb 1984)

Meet the editors

About this issue

Summary

The main focus is of articles in this issue is on what cities and their governments been doing to encourage, and benefit from, art and art-related activity. The contributors explore places for the making of art, also selling art, showing it, enjoying it and exploiting it. From a focus on themes in the first four papers, the contributors turn to places, ranging from Britain to Korea, to the Middle East and the Netherlands.

Martin Crookston is a strategic planning consultant. An urban economist and planner, he was a member of Lord Rogers’s Urban Task Force, where he chaired the Working Group on Design & Transport. He is author of Garden Suburbs of Tomorrow? A New Future for the Cottage Estates and is a member of the Built Environment Editorial Board.

Martin Crookston is a strategic planning consultant. An urban economist and planner, he was a member of Lord Rogers’s Urban Task Force, where he chaired the Working Group on Design & Transport. He is author of Garden Suburbs of Tomorrow? A New Future for the Cottage Estates and is a member of the Built Environment Editorial Board.

Editorial: Arts and the City

About this issue

Summary

The main focus is of articles in this issue is on what cities and their governments been doing to encourage, and benefit from, art and art-related activity. The contributors explore places for the making of art, also selling art, showing it, enjoying it and exploiting it. From a focus on themes in the first four papers, the contributors turn to places, ranging from Britain to Korea, to the Middle East and the Netherlands.

The Call for Papers for this issue of Built Environment aimed to ‘reflect on a broad spectrum of activities from across the world, that help illuminate the role of the arts in forming the city through strategies, whether formal or informal’.

Well, ‘broad’ is definitely right. Arts and the City could be about almost everything. We flirted with the temptation of ‘art-engendered and art-entangled’ places – Montmartre 1890? SoHo 1980? Florence 1450? – but thought, no, that would be a whole different story. Nor are we trying to track down loci of innovation or even creativity, though you’ll find references to Richard Florida and The Rise of the Creative Class (Florida, 2002) on many a page below; and of course we’re fascinated by how innovative art and creative place-making happen and are helped to happen.

The articles in this issue explore places for the making of art, but also selling art, showing it, enjoying it and exploiting it. We’re interested in the places themselves, and what they’re doing about art and culture. We do not just mean visual art: we include the art and places of music, and we could have widened the net to bring in theatre cities (Edinburgh’s Festival, Niagara-on-the Lake?), opera cities (Bayreuth, Verona?) and literary cities (Dublin, recognized in its new Museum of Literature in Ireland).

The Focus

That all said, our main focus is on what cities and their governments have been trying to do to encourage, and benefit from, art and art-related activity of many kinds. This is coupled, inevitably, with trying to understand how arts and the city interact with each other. Our 2005 ‘Music and The City’ issue (Kloosterman, 2005a) made an explicit link of this kind:

If indeed processes of innovation in popular music resemble those in high-tech, then we could also argue the other way round and use popular music to draw broader lessons from studying, notably, the relationship between music and the city.

And added:

It is, first of all, more fun, at least for aficionados…

– which is certainly part of the charm of a subject like art and artists in the city –

… and secondly, and more seriously, the often very-well documented micro history of pop music stars provides us with a window of opportunity to catch a glimpse of the way processes of innovation take place…’. Kloosterman, 2005b, p. 190)

So we’re looking at what happens, and how it happens, as well as the more policy-oriented question of what all the agencies and actors are trying to make happen.

The Big Picture

It is a thirty-to-forty-year story, to which Charles Landry introduces us in his Arts, Culture and The City: An Overview (Landry, 2020). He shows how cities worldwide have come to see that the arts, culture and creativity can help with their aspirations for renewal and revitalization: beginning with bigger cities like Barcelona and Glasgow, but now extending ‘down the hierarchy’ to smaller places which also see the opportunity to go with the grain of local cultures and create energy that can be transformative.

And the ‘creative’ aspect is also, and crucially, about the actions to make places more of a creative milieu, as Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa Nicodemus address in their Arts and the City: Policy and Its Implementation (Markusen and Gadwa Nicodemus, 2020). This is the history of an impressive decade-long policy impetus, inspired by the ‘Creative Placemaking’ initiative (Markusen and Gadwa Nicodemus, 2018) which both authors were closely engaged in, driven federally but implemented locally in many imaginative ways, across the United States. In the United Kingdom, too, recognition of the full-spectrum (not just economic) contribution of the arts is evident in, for example, the recent Arts Council England research report showing that ‘arts and culture are up there with good schools when people make their decisions on where to live’. One of their interviewees said that a strong cultural offer ‘gives the impression that an area respects itself and its historical and cultural heritage’ (Serota, 2019).

Another of the participants in the initial Creative Placemaking endeavour, Anna Marazuela Kim, explicitly links the US and UK experiences in her Can We Design for Culture? Paradigms and Provocations (Kim, 2020). She also brings in a fascinating individual-player perspective in a thoughtful and wide-ranging interview with Sherry Dobbin, a former director of Times Square Alliance and now with Future Cities in London – highlighting the vital role that one person can play in a sector as idiosyncratic and instinctive as arts and culture.

This focus on experience and implementation is carried through in the next article, by Vivien Lovell of the Modus Operandi consultancy: Artists and the Public Spaces of the City (Lovell, 2020). Here, Lovell sets out lucidly and practically the key considerations for Public Art programmes: a field too often strewn with the lost and bathetic leftovers of well-meaning but incoherent investment. A dozen brilliant examples, mainly from London, show how good Public Art can be conceived and integrated.

From Themes to Places

We then shift focus from these largely thematic treatments to a series of articles which look at specific places, and the art and cultural effort within them.

We begin with the artists themselves. In the specific milieu of London’s East End, we see where they are and were, why they were and are there, and how this links (and sometimes doesn’t) to processes of urban change like gentrification. Nick Green – who in fact contributed to the 2005 Music and the City issue (Green, 2005) – maps and describes, in The Holding Option: Artists in East London 1968–2020 (Green, 2020), this world of artistic production and exchange. And he brings us up to 2020 where strategic planning, in the shape of the Greater London Authority, now has a Cultural Infrastructure Plan for London (Mayor of London, 2019) which seeks to shape this hitherto anarchic and ever-changing scene.

The processes Green describes involve a relentless churn of occupation, removal and displacement, highlighted by one of our other authors – Elizabeth Currid-Halkett – in her earlier work about the similar pressures in Manhattan on the SoHo art scene (Currid-Halkett, 2007). It is interesting that some attempt is now being made in East London to soften the displacement pressures: Create London are working with one local council to build live-work artists’ housing, with ‘discounted rent and lifetime tenancies in exchange for running a free daily public programme in the community hall’ (Garrard, 2019, p. 63).

Then we really swing east.

Yasser ElSheshtawy’s Beyond Artwashing: An Overview of Museums and Cultural Districts in Arabia (Elsheshtawy, 2020) sets out a magisterial survey of the blaze of high-profile investments in the cultural sector in the Arab Gulf States, from Louvre Abu Dhabi to the mushrooming of ‘cultural districts’ in cities all over the region. The key actors in this setting are, one might say, only incidentally the artists themselves: these initiatives are very often the pure form of ‘art as city strategy’, with government and corporate enterprise in the driving-seat. Yet they do also relate to the idea that ‘an area respects itself and its historical and cultural heritage’, mentioned above. These are cities, often city-states, who are keen not just to state their claim to international importance, but also to hold on to their people’s culture and history as a maelstrom of globalization sweeps over the Arab world.

We then take a ‘deep dive’ into one of these cultural districts. Alongside the ten lanes of Sheikh Zayed Road, in the Middle Eastern hub city of Dubai, a sort of manufactured ‘rundown-warehousing-district’ has emerged in an area (Al-Quoz) primarily zoned for industry – and barely twenty-five years old. Damien Nouvel recounts its evolution in Organic, Planned or Both: Al-Serkal Avenue: An Art District by Entrepreneurial Action in an Organic Evolutionary Context (Nouvel, 2020). Dubai generally has a district for everything (Media City, Healthcare City, Knowledge Village, etc), but Nouvel shows that Al-Quoz/Al-Serkal is not quite that: it is an unusual variant on Dubai’s characteristic interweave of public and private initiative, with entrepreneurs taking more of the lead and with something of a blind eye from the Municipality, marking it out too from the entirely top-down efforts in most neighbouring cities and states. And of course, ‘art district’ in a trading city like Dubai means that actual artists are not necessarily the dominant form of life as you walk around Al-Serkal.

Onward and eastward, this time to Korea. In Socially Engaged Art(ists) and the ‘Just Turn’ in City Space, Soyoon Choo and Elizabeth Currid-Halkett draw in particular on two means by which art and artists have interacted with urban planning and development choices in ways that illuminate what socially-engaged art can mean in a great city like the Korean capital: especially at a time of enormous change in politics and societal values (Choo and Currid-Halkett, 2020). At one of Seoul’s major plazas, artists helped shift the role of that space towards public dialogue; whilst more broadly urban policies have responded so that regeneration plans and community-led planning involve the arts/culture and ‘just city’ norms of equity, democracy, and diversity.

The Art of Music

Our last two articles home in the role of one particular art – music – in shaping perceptions and realities of the modern city. We are back to a world where the artist is key, and one where there are many questions about the role of outside agencies in supporting, shaping and inevitably hindering the creative potential. Like the 2005 Music and the City issue, we are interested in place and music:

The virtuous circle of a city making music and music making a city shows how places and their particular histories still matter in an era where (digitalized) music seems to be first and foremost a part of the global space of flows. (Kloosterman, 2005b, p. 182)

We move back west, to two European cities. First, to Den Haag/The Hague, where Robert Kloosterman (editor of the 2005 issue) and Amanda Brandello describe the intense but ultimately quite short-lived story of that city’s enormously vibrant beat music scene. Their article, There Is Music to Play, Places to Go, People to See: An Exploration of Innovative Relational Spaces in the Formation of Music Scenes: The Case of the Hague in the 1960s (Brandello and Kloosternman, 2020) shows how specific places in the city almost by accident created, via an atmosphere of shared interests, trust and competition, a critical mass of musicians and their ecosytem which drove an extraordinarily lively and successful local music scene. Yet just as quickly, it unravelled: supporting, perhaps, another observation in the 2005 issue that ‘large cities are, in the long run, in an advantageous position vis-à-vis smaller cities that usually only thrive one style or fashion era and not much beyond’ (Kloosertman, 2005b, p. 181).

And then, finally to Liverpool. Ian Wray’s article The Pool of Life: Liverpool, Rock Music and the Roots of Creativity (Wray, 2020) looks at the city and its history, at its famous sons the Beatles and the shaping of their careers and markets in the 1960s, at the city’s subsequent boom of 1980s punk and post-punk, and at what these histories tell us about how the creative impulse emerges in cities. Although a city can – and Liverpool does – have policies to try and replicate this success and build on it, a key conclusion is that musical education, and a support network for and of musicians, are probably the crucial elements.

Which perhaps brings us back to creativity. The act of creating art, whether a guitar riff, a concerto, a painting or a play, is a personal and unprogrammed thing. Nonetheless, cities can help provide the conditions for that creation to happen, and for arts and culture to thrive. The contributions to this issue show some of the ways that this can be done. And how creative places can be made and nurtured in cities and towns of every kind and in every setting.

REFERENCES

- Brandello, A. and Kloosternman, R. (2020) There is music to play, places to go, people to see: an exploration of innovative relational spaces in the formation of music scenes: the case of the Hague in the 1960s. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 298–312.

- Choo, S. and Currid-Halkett, E. (2020) Socially engaged art(ists) and the ‘just turn’ in city space: the evolution of Gwanghwamun Plaza in Seoul, South Korea. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 279–297.

- Currid-Halkett, E. (2007) The Warhol Economy: How Fashion, Art, and Music Drive New York City. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ElSheshtawy, Y. (2020) Beyond artwashing: an overview of museums and cultural districts in Arabia. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 248–261.

- Florida, R. (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class. New York: Basic Books.

- Garrard, H. (2019) How can we save space in our cities for artists? Art Quarterly, Winter.

- Green, N. (2005) Songs from the woods and sounds from the suburbs: a folk, rock and punk portrait of England, 1965–1977. Built Environment, 31(3), pp. 255–270.

- Green, N. (2020) The holding option: artists in East London 1968–2020. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 229–247.

- Kim, A.M. (2020) Can we design for culture? Paradigms and provocations. 46(2), pp. 199–213.

- Kloosterman, R. (ed.) (2005a) Music and the City. Built Environment, 31(3).

- Kloosterman, R. (2005b) Come together: an introduction to cities and music. Built Environment, 31(3), pp. 181–191.

- Landry, C. (2020) Arts, culture and the city: an overview. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 170–181.

- Lovell, V. (2020) Artists and the public spaces of the city. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 214–228.

- Markusen, A. and Gadwa Nicodemus, A. (2018) Creative placemaking: reflections on a 21st century American arts policy initiative, in Courage, C. and McKeown, A. (eds.) Creative Placemaking: Research, Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Markusen, A. and Gadwa Nicodemus, A. (2020) Arts and the city: policy and its implementation. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 182–198.

- Mayor of London (2019) Cultural Infrastructure Plan. London: Greater London Authority.

- Nouvel, D. (2020) Organic, planned or both: Al-Serkal Avenue: an art district by entrepreneurial action in an organic evolutionary context. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 262–278.

- Serota, N. (2019) The arts can restore pride to Britain’s towns. Guardian, 27 August.

- Wray, I. (2020) The pool of life: Liverpool, rock music and the roots of creativity. Built Environment, 46(2), pp. 313–332.

Arts and the City

About this issue

Summary

The main focus of the articles in this issue is on what cities and their governments been doing to encourage, and benefit from, art and art-related activity. The contributors explore places for the making of art, also selling art, showing it, enjoying it and exploiting it. From a focus on themes in the first four papers, the contributors turn to places, ranging from Britain to Korea, to the Middle East and the Netherlands.

Contents

-

Arts and the City

MARTIN CROOKSTON -

Arts, Culture and the City: An Overview

CHARLES LANDRY -

Arts and the City: Policy and Its Implementation

ANN MARKUSEN and ANNE GADWA NICODEMUS -

Can We Design for Culture? Paradigms and Provocations

ANNA MARAZUELA KIM -

Artists and the Public Spaces of the City

VIVIEN LOVELL -

The Holding Option: Artists in East London, 1968–2020

NICK GREEN -

Beyond Artwashing: An Overview of Museums and Cultural Districts in Arabia

YASSER ELSHESHTAWY -

Organic, Planned or Both: Alserkal Avenue: An Art District by Entrepreneurial Action in an Organic Evolutionary Context

DAMIEN NOUVEL -

Socially Engaged Art(ists) and the ‘Just Turn’ in City Space: The Evolution of Gwanghwamun Plaza, Seoul, South Korea

SOYOON CHOO and ELIZABETH CURRID-HALKETT -

There’s Music to Play, Places to Go, People to See! An Exploration of Innovative Relational Spaces in the Formation of Music Scenes: The Case of The Hague in the 1960s

AMANDA BRANDELLERO and ROBERT KLOOSTERMAN -

The Pool of Life: Liverpool, Rock Music and the Roots of Urban Creativity

IAN WRAY

Editorial: Space-Sharing Practices in the City

About this issue

Summary

As the editors explain in their introduction, the papers in this issue can be divided into two parts. The first part (three articles) provides a conceptual foundation for understanding space-sharing practice in the city, while the six papers of the second part are empirical studies of emerging space-sharing practices, each investigating a specific form of sharing space and/or type of shared space.

Throughout history, the city has been quintessentially a shared space. But today, with the increasing urban population density and the ubiquity of the Internet of Things (IoT), the city has become an even more conducive site for complex sharing activities (Cohen and Munoz, 2016). One such complex activity is what we term space-sharing practice: an emerging urban phenomenon that has so far accreted in new forms of sharing spatial resources, the creation of new shared spaces, and the production of new socio-spatial sharing relations (Chan and Zhang, 2018). Central to space-sharing practice is the recognition that the physical space can be designed and configured into a shareable resource, and that there are certain resources that would be more effectively shared in actual and spatial environment (see Katrini, 2018; Piccinno, 2018). Following this, it may be possible to specify further space-sharing practice through a threefold distinction: the space of sharing (i.e. the different ways of sharing spaces and the different typologies of shared space), space in sharing (i.e. the different roles that space plays in facilitating or enabling sharing activities and practices), and finally, space for sharing (i.e. how environmental design can create affordance for sharing and enable social transformations).

Nevertheless, our understanding of this phenomenon remains nascent, uneven and incomplete. Existing literature mostly centres around the Sharing Economy, which focuses on the social, business, political, organizational and regulatory dimensions of this form of economy (e.g. Botsman and Rogers, 2010; Schor, 2016; Frenken and Schor, 2017; Slee, 2015; Schor and Attwood-Charles, 2017), at the exclusion of acknowledging space, let alone the systematic investigation of space of sharing, space in sharing and space for sharing. In the views espoused by the Sharing Economy, sharing activities are often narrowly understood or primarily framed on the basis of economic transactions, and space is merely presumed as the background reality that accommodates such transactions. As a result, the spatial dimension of sharing has yet to be recognized as an essential variable in elucidating the phenomenon of sharing. Clearly, this also means that the important examination of emerging space-sharing practices in contemporary cities has so far remained elusive.

This knowledge gap is salient, and especially urgent, for the following reasons. First, space is both integral and constitutive to sharing in the city, especially to new space-sharing practices. Many of these activities – for instance, car sharing, bike sharing, office sharing, and many more – are essentially place-based (Cohen and Munoz, 2016). This means that not only are the spatial attributes of these places likely to condition the possibilities and processes of sharing, but sharing activities are also anticipated to impact the ambience, constitution and usage patterns of these places (Chan and Zhang, 2018). For instance, physical spaces can be purposefully configured to heighten the proximity effect (Chan, 2019) and to make serendipitous encounters more likely (Olma, 2016) which, in turn, may lead to the formation of new collaborative networks that are likely to further modify and adapt these spaces for their specific needs. This can be found in the case of flat sharing, where spatial proximity engenders the proximity effect. When this is amicable it can lead to flatmates engaging in more communal living and sharing more spaces, consequently transforming the shared space that can facilitate, as well as reflect, their enhanced relations.

Second, the impact of many space-sharing practices is either inherently spatial or manifested spatially. Taking the case of dockless bikeshare programmes for instance, the benefit of this sharing practice – that is, the freedom and convenience to park and pick up bicycles anywhere in the city – is often achieved at the cost of inconveniencing others who share the same urban space as the riders. In other words, the innovative way of sharing space itself turns out to be the cause of the problems encountered in this shared space. More often, impacts of space-sharing practices are registered through the ‘ripple effects’ of the sharing economy (Schor, 2016). In this case, space may not be immediately or directly affected by sharing practice, but as a stage in this sharing practice, it will be ineluctably implicated in its subsequent impacts and influences. In many cities, for example, the rapid consumption of otherwise more valuable urban space for new commercial properties and the associated problems of congestion, parking and pollution are closely linked to the dramatic growth and prevalence of Airbnb (Gurran and Phibbs, 2017).

Furthermore, space is more than a shareable resource (Benkler, 2004); it is often a generative reality where societies and cultures unfold and evolve (McLaren and Agyeman, 2015). Today, as a result of space-sharing practices, an increasing number of new typologies of shared space have been created. These new spatial typologies in turn enhance the sharing activities that take place within them and, in this process, foster the formation of new social and economic relations. Most notable among them are coworking spaces (Spinuzzi, 2012; Gandini, 2015; Merkel, 2017) and hackerspaces (Williams and Hall, 2015; Davies, 2017) which not only accommodate and facilitate an emerging work culture and a new lifestyle, but also cultivate and spur mutual learning (Merkel, 2017), collaboration and socialization (Davies, 2017). Anticipating a new horizon for transforming social relationships, space-sharing practices are also, arguably, laying the ground for urban commons (Harvey, 2012). While the production and maintenance of urban commons certainly require much more than sharing (Kip et al., 2015), spaces, and specifically space-sharing practices, are nonetheless the key precursor to urban commons in many cases. For example, cases of cooperative housing (or co-housing) and community gardens all point to a common origin of some forms of space-sharing practices. This aspect of urban commons has been largely neglected in the present discourse, of which a majority tends to focus mainly on the commoning process to the exclusion of discussing the precondition of space and the spatial relations that prefigure this process.

In order to bridge this knowledge gap, this special issue brings together a set of contributions from different disciplinary perspectives that provide new insights into emerging space-sharing practices in the city. Specifically, all the articles can be seen as a concerted effort that attempts to respond to the issues discussed above, and address primarily, but not limited to, the following questions:

- What are the spatial attributes of different space-sharing practices, and the associated economics, policies, governance, and organizations for sharing?

- How does the spatial environment of the city condition space-sharing practices, and conversely how do they shape and transform existing, and produce new, urban spaces?

- What are the impacts of space-sharing practices on urban spaces?

- What new socio-spatial relations are produced by space-sharing practices? And finally,

- How can we encourage meaningful space-sharing practices, amplifying the positive and mitigating the negative impacts, through purposeful design and interventions?

While these questions can hardly represent the full set of inquiries pertaining to the spatial dimension of sharing, it is hoped that they can, nonetheless, serve as a starting point for developing a fuller agenda for systematic study of space-sharing practice.

This issue can be read in two parts. The first three articles, which form the first part, together provide a conceptual foundation for understanding space-sharing practice in the city. It begins with an empirical study from John (2020), examining how the very concept of sharing is perceived and used by people from different positions of the sharing economy. A particular focus is devoted to whether the presence of money is a counterindication for sharing. By questioning fixed definitions of sharing and revealing the controversies revolving around this concept, John’s work calls for a contextualized and dynamic understanding of sharing. In this way, it brings out the crucial question of where, or what should be the starting point for, investigating space-sharing practices.

This is followed by Frenken and Pelzer’s (2020) work that highlights the importance of an appropriate policy and institutional framework for sharing practice. This study provides a critique of the innovation logic, deemed as ‘reverse technology assessment’ that allows many platforms of the sharing economy to be launched without any ex ante assessment, resulting in various negative impacts and externalities upon urban spaces. Following this, the authors examine the potential of an alternative policy framework, regarded as the ‘right to challenge’ and emphasize the need to develop localized cooperative sharing platforms in order to safeguard public interests and enable public participation in the sharing process.

While the first two articles throw new light on the wider environment of space-sharing practice, the third article from Widlok (2020) charts the spatial attributes of sharing, which can be summarized as the spatial condition for creating co-presence as one of the main strategies for demanding a share and enabling sharing. Mirrored in both the ethnographic cases of primitive hunter-gatherer settlements and present sharing activities, the relation between space and sharing, as the author highlights, is inherently complex and nuanced; that is, while features of the built environment such as bodily proximity and high permeability are proven to affect the occurrence of sharing, it is nonetheless almost impossible to formularize the link between space and sharing, because sharing as a social practice, both in history and today, is characterized by special mutuality, temporality and sequentiality. For Widlok, therefore, learning from vernacular social forms and processes that involve the ordering of the built environment in relation to sharing practices is possibly a rigorous approach to understanding and unpacking space-sharing practice.

The articles in the second part are empirical studies of emerging space-sharing practices, each investigating a specific form of sharing space and/or type of shared space. What is common among these papers is that space-sharing practice is not merely analysed and discussed as an emerging phenomenon in itself; rather that it can serve as a prism through which new insights on urban processes can be gained and new urban opportunities envisioned. Huang et al. (2020) present a study that examines coworking space in Beijing. It reveals that the recent boom of coworking spaces in the city is not only associated with the fast-growing creative industry catering for the newly emerging work culture, but is also an efficient mechanism for revitalizing many low-value areas and dilapidated properties across the city. Nevertheless, this impact, deemed positive in this article, is on the one hand dependent on the quality of public facilities in the wider urban environment such as public transport network and education institutions, and on the other, strongly conditioned by the goals of the profit-driven market economy.

Following this, Long and Zhao (2020) develop a Mobike Riding Index to study the dockless bikeshare programme in China, using a large set of Mobike riding data covering almost 300 cities across the country. The index quantifies numerous spatial characteristics of the physical urban environment related to cycling and is shown to be a powerful new tool to understand bike sharing and to support relevant decision-making in urban planning and design. The paper reveals the potential of leveraging crowdsourced data to study new space-sharing activities and, more generally, it suggests an alternative for empirical research on sharing that has been acutely impeded by the lack of access to privately-owned datasets (Frenken and Schor, 2017).

Moving from China to Singapore, the next article by Seah and Teo (2020) presents a new typology of architecture – the integrated community hub – that is deliberately designed for agglomerating various sharing activities and generating new social interactions within and beyond a local community. Premised on the concept of Whole-Of-Government, the integrated community hub is not merely conceived as a large-scale, multi-functional shared space but more than this, as a spatial device that enables public engagement during planning, which then fosters a broader sharing of government resources and public services. This study opens a new horizon for creating spatial typologies of sharing that can function as, to use the authors’ words, ‘social condensers’ for the production of new social relationship networks and enhanced community building.

The complementary relation between space-sharing practice and community building is further unpacked in the next two papers, which focus on the empirical study of how individuals and communities share urban spaces. Both illustrate how community engagement can be catalysts in creating and sustaining shared spaces in the city and verse visa. Cho and Kriznik (2020) present an ethnographic study of appropriating alleys as collectively created shared spaces to foster communal life in two local neighbourhoods of Seoul. In this study, community engagement is understood as an instrumental process through which local residents’ awareness of alleys as shareable spatial resources is awakened and shared alleys are then constituted and maintained as a result of their collective action and collaboration. The shared alleys in turn also contribute to strengthening social relationship networks and help to sustain the communal life and shared identities of the neighbourhoods.

Gopalakrishnan and Chong (2020), bring the focus back to Singapore and examine community gardens as shared urban green spaces. Community engagement in this case is discussed as a participatory process of place-keeping, the step after place-making that is often neglected in urban planning and design. This study argues that actively engaging residents in place-keeping can add a new layer to space-sharing practice even beyond production of new socio-spatial relations – that is, encouraging shared responsibility and maintaining a collective effort towards transitioning a public space into a commons. Critical to this community-led place-keeping approach, as the authors point out, is the development and implementation of an innovative participatory governance system with a conscious balance in power and relations between municipal authorities and residents. Common to the above two articles, and especially evident in the second one, is that space-sharing practice seems to be presumed as a pre-condition that anticipates the birth of new urban commons from within the community.

The last article by Stavrides (2020) tackles the connection between space-sharing practice and urban commons. It argues that collectively creating and sharing spaces is an effective means of reclaiming commons in contemporary cities that are increasingly characterized by segregation, enclosure and inequality. Based on cases of housing movements experienced by the marginalized populations in three Latin American countries, this study highlights the transformative potential of commoning with respect to urban spaces. As the author highlights, it is the commoning process that unleashes the power of collective creativity and collaboration, which in turn transforms the physical urban environment into shared places of habitation and produces new forms of social relations. Also, it is in the commoning process that space-sharing practice plays the dual role as both a shaping factor of power negotiation and a mechanism of social bond creation, catalysing new political mobilization and organization.

Taken together, the contributions to this issue can be viewed as a wide range of case studies and examples of space-sharing practices from diverse cultural and geographical contexts. In addition to offering a global perspective, it is also hoped that these studies open up an opportunity that allows readers to identify commonalities of vision, approach, impact, and ethics – among many other parameters – that together form a preliminary framework for understanding space-sharing practice in cities. It is noteworthy that half the articles examine emerging sharing practices in East and Southeast Asian cities. From this point of view, this issue also contributes by starting to address the severe lack of systematic studies and documentation of sharing activities in these geographical regions.

Besides the cross-geographical coverage, these papers also present, from multiple disciplinary angles, different approaches to studying space-sharing practice. As indicated above, while linguistic pragmatics, policy analysis and ethnography are employed to establish the conceptual foundations, classical qualitative methods as well as big data analytics have also been applied to the empirical investigations. Especially notable is the contribution by two architects – Seah and Teo (2020) – who, in contrast to academic writers, offer an elaborate example of design research, where design variables, social factors and architectural processes are richly intertwined to create a detailed account of a new typology of shared space.

Read in a sequence, the articles can be seen to be strengthening the narrative that space-sharing practice should not be understood just as a transactional activity or as a category of the sharing economy. Rather it should be seen as a new urban phenomenon that sheds light on the spatial dimension of sharing: space can be shared in innovative ways and shaped into new shared typologies; space can play different roles in facilitating and enabling sharing activities; and space can be specifically designed to open up new opportunities for sharing, which then lead to the formation of new socio-spatial relations and more significantly, the potential production of the urban commons. Pushing the knowledge boundary in this direction, these studies also prompt further research questions – for instance, to what extent, and in what ways, can space-sharing practice catalyse the formation of the urban commons? And conversely, whether, and if so, how can the institutional framework of urban commons contribute to enabling more equitable and democratic space-sharing practices?

This issue owes an immense debt of gratitude to all the contributors who responded to our invitation to contribute and who shared their work and insights generously with little reservation. Special thanks are also due to the reviewers who not only gave their time and expertise to perform a careful and critical reading of the manuscripts but also subsequently, offered constructive and inspiring feedback to the contributors. The collective efforts of this special group of scholars and practitioners clearly embody the spirit of sharing.

REFERENCES

- Benkler, Y. (2004) Sharing nicely: on shareable goods and the emergence of sharing as a modality of economic production. The Yale Law Journal, 114(2), pp. 273–358.

- Botsman, R. and Rogers, R. (2010) What is Mine is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption. New York: Harper.

- Chan, J.K.H. (2019) Urban Ethics in the Anthropocene: The Moral Dimensions of Six Emerging Conditions in Contemporary Urbanism. Singapore: Palgrave.

- Chan, J.K.H. and Zhang, Y. (2018) Sharing space: urban sharing, sharing a living space, and shared social spaces. Space and Culture. http://doi.org/10.1177/1206331218806160.

- Cho, I.S. and Križnik, B. (2020) Sharing Seoul: appropriating alleys as communal space through localized sharing practices. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 99–114.

- Cohen, B. and Munoz, P. (2016) Sharing cities and sustainable consumption and production: towards an integrated framework. Journal of Cleaner Production, 134, pp. 87–97.

- Davies, S.R. (2017) Hackerspaces: Making the Maker Movement. Malden, MA: Polity.

- Frenken, K. and Pelzer, P. (2020) Reverse technology assessment in the age of the platform economy. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 22–27.

- Frenken, K. and Schor, J.B. (2017) Putting the sharing economy into perspective. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 23, pp. 3–10.

- Gandini, A. (2015) The rise of coworking spaces: a literature review. Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization, 15(1), pp. 193–205.

- Gopalakrishnan, S. and Chong, K.H. (2020) The prospect of community-led place-keeping as urban commons in public residential estates in Singapore. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 115–138.

- Gurran, N. and Phibbs, P. (2017) When tourists move in: how should urban planners respond to Airbnb? Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(1), pp. 80–92.

- Harvey, D. (2012) Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso.

- Huang, H., Liu, Y., Liang, Y., Vargas, D. and Zhang, L. (2020) Spatial perspectives of coworking spaces practices in Beijing. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 40–54.

- John, N.A. (2020) What is meant by ‘sharing’ in the sharing economy? Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 11–21.

- Katrini, E. (2018) Sharing culture: on definitions, values, and emergence. The Sociological Review Monographs, 66(2), pp. 425–446.

- Kip, M., Bieniok, M., Dellenbaugh, M., Muller, A.K. and Schwegmann, M. (2015) Seizing the (every)day: welcome to the urban commons! in Dellenbaugh, M., Kip, M., Muller, A.K., and Schwegmann, M. (eds.) Urban Commons: Moving Beyond the State and Market. Basel: Birkhauser, pp. 9–25.

- Long, Y. and Zhao, J. (2020) What makes a city bikeable? A study of intercity and intracity patterns of bicycle ridership using mobike big data records. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 55–75.

- McLaren, D. and Agyeman, J. (2015) Sharing Cities: A Case for Truly Smart and Sustainable Cities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Merkel, J. (2017) Coworking and innovation, in Bathelt, H., Cohendet, P., Henn, S., and Simon, L. (eds.) The Elgar Companion to Innovation and Knowledge Creation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 570–586.

- Olma, S. (2016) In Defence of Serendipity: For a Radical Politics of Innovation. London: Repeater Books.

- Piccinno, G. (2018) Between the digital and the physical: reinventing the spaces to accommodate sharing services, in Bruglieri, M. (ed) Multidisciplinary Design of Sharing Services. Cham: Springer, pp. 41–51.

- Schor, J.B. (2016) Debating the Sharing Economy. Journal of Self-Governance & Management Economics, 4(3), pp. 7–22.

- Schor, J.B. and Attwood-Charles, W. (2017) The ‘sharing’ economy: labor, inequality, and social connection on for-profit platforms. Sociology Compass, 11(8), e12493. http://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12493.

- Seah, C.H. and Teo, S. (2020) Learning from our tampines hub: co-generative hubs for urbanism. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 76–98.

- Slee, T. (2015) What’s Yours is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy. New York: OR Books

- Spinuzzi, C. (2012) Working alone together: coworking as emergent collaborative activity. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 26(4), pp. 399–441.

- Stavrides, S. (2020) Reclaiming the city as commons. Learning from Latin American housing movements. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 139–154.

- Widlok, T. (2020) Sharing, presence and the built environment. Built Environment, 46(1), pp. 28–39.

- Williams, M. and Hall, J. (2015) Hackerspaces: a case study in the creation and management of a common pool resource. Journal of Institutional Economics, 11(4), pp. 769–781.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This special issue is part of the project, NUS-Tsinghua Design Research Initiative sponsored by Ng Teng Fong Charitable Foundation (Hong Kong). Project website: www.nt-drisc.org.

Meet the editors

About this issue

Summary

As the editors explain in their introduction, the papers in this issue can be divided into two parts. The first part (three articles) provides a conceptual foundation for understanding space-sharing practice in the city, while the six papers of the second part are empirical studies of emerging space-sharing practices, each investigating a specific form of sharing space and/or type of shared space.

Ye Zhang is Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore. His research interests are mainly in urban morphology and the urban transformation of Asian cities. He is the Director and co-founder of NUS-Tsinghua Design Research Initiative – Sharing Cities.

Ye Zhang is Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, National University of Singapore. His research interests are mainly in urban morphology and the urban transformation of Asian cities. He is the Director and co-founder of NUS-Tsinghua Design Research Initiative – Sharing Cities.

Jeffrey Kok Hui Chan is Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design. He is the author of Urban Ethics in the Anthropocene (2018) and has published widely in the fields of planning, and design and technology.

Jeffrey Kok Hui Chan is Assistant Professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design. He is the author of Urban Ethics in the Anthropocene (2018) and has published widely in the fields of planning, and design and technology.

Space-Sharing Practices in the City

About this issue

Summary

As the editors explain in their introduction, the papers in this issue can be divided into two parts. The first part (three articles) provides a conceptual foundation for understanding space-sharing practice in the city, while the six papers of the second part are empirical studies of emerging space-sharing practices, each investigating a specific form of sharing space and/or type of shared space.

Contents

-

Space-Sharing Practices in the City

YE ZHANG and JEFFREY KOK HUI CHAN -

What is Meant by ‘Sharing’ in the Sharing Economy?

NICHOLAS JOHN -

Reverse Technology Assessment in the Age of the Platform Economy

KOEN FRENKEN and PETER PELZER -

Sharing, Presence and the Built Environment

THOMAS WIDLOK -

Spatial Perspectives of Coworking Spaces and Related Practices in Beijing

HE HUANG, YANGFANQI LIU, YUEBING LIANG, DAVID VARGAS and LU ZHANG -

What Makes a City Bikeable? A Study of Intercity and Intracity Patterns of Bicycle Ridership using Mobike Big Data Records

YING LONG and JIANTING ZHAO -

Learning from Our Tampines Hub: Co-Generative Hubs for Urbanism

CHEE HUANG SEAH and SHAWN ENG KIONG TEO -

Sharing Seoul: Appropriating Alleys as Communal Space through Localized Sharing Practices

IM SIK CHO and BLAŽ KRIŽNIK -

The Prospect of Community-Led Place-Keeping as Urban Commons in Public Residential Estates in Singapore

SRILALITHA GOPALAKRISHNAN and KENG HUA CHONG -

Reclaiming the City as Commons. Learning from Latin American Housing Movements

STAVROS STAVRIDES - Publication Reviews

Meet the editors

About this issue

Summary

The ten papers in the issue cover three continents and seven countries representing a true diversity of settings. Each paper offers new insights into how commuting journeys vary across space and how this is influenced by spatial development and economic, technological and cultural change. All the papers give consideration to how commuting is changing in the setting examined, whether explicitly by analysing longitudinal data or implicitly by interpreting their results in relation to historical developments.

Kiron Chatterjee is Associate Professor in Travel Behaviour at the Centre for Transport & Society at UWE Bristol. His research seeks to understand the way in which people travel, how this is influenced by the transport system and society and the impacts of transport on people’s lives. This research is aimed at anticipating future mobility trends and designing transport systems and services that meet the needs of different members of the population.

Kiron Chatterjee is Associate Professor in Travel Behaviour at the Centre for Transport & Society at UWE Bristol. His research seeks to understand the way in which people travel, how this is influenced by the transport system and society and the impacts of transport on people’s lives. This research is aimed at anticipating future mobility trends and designing transport systems and services that meet the needs of different members of the population.

Ben Clark is a Senior Lecturer in Transport Planning and Engineering at the Centre for Transport & Society at UWE Bristol. His research interests centre on travel behavior, with a specific focus on the application of longitudinal research methods to explore how and why behaviors change over the course of people’s lives.

Editorial: Changing Patterns of Commuting

About this issue

Summary

The ten papers in the issue cover three continents and seven countries representing a true diversity of settings. Each paper offers new insights into how commuting journeys vary across space and how this is influenced by spatial development and economic, technological and cultural change. All the papers give consideration to how commuting is changing in the setting examined, whether explicitly by analysing longitudinal data or implicitly by interpreting their results in relation to historical developments.

Cities across the globe are reinventing themselves, driven by a variety of forces (Lyons et al., 2018). At the same time, technological change is dramatically altering the nature of employment and transport systems are on the cusp of radical change with the potential for wider adoption of new mobility services and autonomous vehicles. As city landscapes, working practices and transport systems change, so does the nature of the commute – traditionally a regularly repeated journey between a fixed home and work (or educational) location, but increasingly a more ‘slippery’ phenomenon (Le Vine et al., 2017).

Commuting has always been an important focus of transport and land-use policies in urban areas. During the morning and evening ‘rush hours’, transport networks are under pressure with peak period traffic having multiple negative impacts on the functioning of cities and on the quality of urban environments (Eddington, 2006). Commuting has also been shown to affect the physical and mental health of workers (Chatterjee et al., 2019). Studies of commuting are carried out across different disciplines which makes it difficult to get an overall appreciation of the topic. In this issue of Built Environment, we aim to bring together a variety of perspectives and assessments of the state of commuting in different parts of the world and how it is evolving.

In particular, we reached out to academics across the globe for contributions on the following three themes:

◆ The changing nature of the commute, particularly in relation to changing city landscapes, working practices and transport systems;

◆ Spatial variation and inequalities in commuting practices; and

◆ The commute experience and how this is affected by urban form and transport systems.

The ten papers in the issue cover three continents and seven countries representing a true diversity of settings. Each paper offers new insights on how commuting journeys vary across space and how this is influenced by spatial development and economic, technological and cultural change. All the papers give consideration to how commuting is changing in the setting examined, whether explicitly by analysing longitudinal data or implicitly by interpreting their results in relation to historical developments.

Two papers look at how distribution of economic activity influences commuting patterns. Schleith et al. (2019) compare commuting distances across metropolitan areas in the United States and calculate ‘Excess Commuting’ measures (representing the difference between the theoretical minimum total commuting distance in a settlement and the observed commuting distance). The Excess Commuting measures are used to identify three categories of urban form amongst the fifty-three metropolitan areas: (i) sprawling; (ii) polycentric and (iii) monocentric. It is then shown that polycentric urban forms are associated with shorter commuting distances. This finding is echoed in Nielsen’s (2019) study of the effect on commuting distances of the emergence of ‘subcentres’ in the Copenhagen urban region. Living close to a subcentre with a minimum of 10,000 jobs is found to be associated with shorter commute and daily travel distances, and a higher probability of using public transport/walking/cycling. Nielsen points out, however, that proximity to the dominant regional subcentre (with over 300,000 jobs) has a stronger effect on commute behaviour than proximity to subcentres.

Two papers look at the how the quality of employment available influences commuting. Coombes (2019) examines why average commuting distances in industrial towns in the north-west of England are shorter than the national average. He discovers that commute distances in the North-West ‘are less divergent from the national average than are the longer distances commuted in and near London’. The longer average commute distances around London are explained by the availability of higher income jobs available in the city, which compensate for longer commutes, while the shorter average commute distances in the North-West are explained by the absence of more attractive jobs in neighbouring settlements than are available locally. Hence the distribution of commute distances in a region is shown to be governed by labour market geography rather than individuals in different regions making different employment decisions.

Sharma (2019) looks at the extent to which workers in India are moving across rural and urban boundaries to access work and how this is affected by labour market conditions. He shows that daily commuting from rural to urban areas is particularly prevalent in the Delhi National Capital Region and that both rural-to-urban and urban-to-rural are common in urbanized, industrialized regions of the country. He shows that rural to urban commuting is driven by underemployment in rural areas and the potential to gain higher wages by commuting from rural to urban areas. He suggests ‘commuting by workers acts as an important bridge between rural and urban areas, without significantly adding a burden on cities in terms of housing, access to public services and ensuring balanced growth in rural economy with backward and forward linkages’.

Three papers look at variations in commuting behaviour within a global city region and how this is evolving. Jain and Hecht (2019) look at commuting patterns in the Delhi National Capital Region and examine how distances travelled and modes used vary for residents living in different parts of the region. They show the highest proportion of private motorized transport use occurs for residents on the fringe of the core city area, where multinational offices and international factories have located, while non-motorized transport use is highest within the city core and in rural peripheral areas of the region. They show longer distance commuting is more prevalent in rural parts of the region and predominantly undertaken by public transport.

Zheng et al. (2019) examine the impact of urban sprawl in Beijing on the commuting behaviours of different social groups. They confirm ‘the decoupling of home and work locations’ in Beijing following the abolishment of the ‘work unit’ (danwei) planning system (through which workers were deliberately housed close to workplaces). They find that a poor ‘urban adversity group’ is clustered in parts of the city that were formerly rural villages, have much higher levels of self-containment and are more reliant on walking and cycling. By contrast, a ‘suburban comfort’ group of younger, wealthier residents have longer commutes with greater reliance on public transit and car.

Maciejewska et al. (2019) concentrate on the changing pattern of commuting within the New York Metropolitan region with a focus on working single mothers, although their results are relevant to all workers. They find single mothers have been suburbanizing over time and can no longer be considered to be predominantly located in inner city areas. They also find that single mothers use public transport more than married mothers and, like the rest of the population of New York, have moved away from car commuting to public transport commuting. They conclude therefore that transit provision is vital in the suburbs to provide single mothers with reasonable access to job opportunities.

The paper by Blumenberg and King (2019) looks at the general trend in commuting distances across all Metropolitan areas of the United States between 2001 and 2017. They look at how this has differed by income and find that commute distances have increased over time for both low-income and high-income workers, but more so for low-income workers and more for those living in low-density areas. Their analysis leads them to conclude that the increasing commute distances of low-income workers over time are primarily explained by a higher proportion of them living in the suburbs, rather than the commute distances of low-income workers increasing over time.

The two remaining papers examine how commuting practices are changing as the nature of employment changes. Ravalet and Rérat (2019) look at teleworking trends in Switzerland and find an increase in teleworking from 21 per cent of workers in 2010 to 24 per cent of workers in 2015. Most teleworkers only occasionally work away from their main office with three-quarters doing this on less than three in ten occasions. They show that teleworking is associated with greater education, higher income jobs and flexibility of working hours and that teleworking is emerging over time more strongly for particular population groups (men and the over thirties). They also reveal that ‘teleworkers live further from their place of work than’ non-teleworkers and that teleworkers travelled further overall than non-teleworkers over the course of a working week (as a consequence of living further from work and undertaking additional non-work trips on teleworking days). They suggest therefore that teleworking ‘may consequently decrease the propensity for residential relocation and increase tolerance for long distance commuting’.

Plyushteva (2019) offers a new angle for looking at the commute by exploring how choices over commuting options and experiences of the commute are influenced by co-workers. She looks at this in Sofia, Bulgaria, which has seen rapid suburban development since the collapse of state socialism in 1989, including the emergence of a burgeoning tourist sector in the historic centre and business and technology parks at fringe locations of the city. From her qualitative research with office workers and shift workers in the tourism and hospitality sector she is able to show how workers manage challenging commutes. She found options available to workers could be highly dependent on provisions made by managers and that travelling together with co-workers could be both a source of comfort or unease.