The Instrumentalization of Landscapes in Contemporary Cities

About this issue

Summary

To what extent have we commodified landscapes and nature? How has this commodification influenced life in the city, including urban processes? Where do efforts to reclaim space within the city for nature fit in the power dynamics within cities? The papers in this issue present three perspectives on this instrumentalization of landscape and nature in cities: the paradigmatic, the urban and regional, and the local/personal.

“Landscape is a medium found in all cultures” - W.T.J., Mitchell, 2002

Landscape and Nature in Contemporary Cities

Key Factors in Greening Cities

- Governmental institutions mainly initiate generic policies, with a reference to broader principles stated by international institutions such as the UN, EU, and so on. As such they tend to be a-contextual, supporting initiatives that increase ecological as well economic value of sites. In addition, governmental policies play a significant role in building a consensus around the concept of sustainability and resiliency, so making a city more attractive for citizens and for foreign and local investment.

- Municipalities focus on the development of landscape projects, conceived and programmed for a specific site, as well as cities’ developing infrastructure that would support recycling and greening. Though they might be adjusted to a particular city or culture, the development of projects and infrastructure are based on similar rational and design strategies. Especially in the last twenty years, landscape design projects have taken on a kind of homogeneous approach in the quest of balancing urbanization and densification.

- Local/individual practices represent an important level in the absorption of the ecological turn. It is the local initiatives and practices of individuals that contribute to the spread of green in contemporary city; individuals and collective subjectivities (e.g. associations, cooperatives, movements) take care of the green in their urban environment, from the scale of the individual urban gardening to the communal public green. Such practices are usually very encouraged by institutions and local governments, because they also work as a means to enhancing a sense of community, belonging and urban health, beyond increasing the landscape materiality of the city.

The Instrumentalization of Landscape: The Paradigmatic, the Urban, and the Personal Levels

-

The Paradigmatic Perspective focuses on the ideology of greening the city. Federico Ferrari’s paper, Reactionary Landscape: the Discourse of Naturalism as a Grand Narrative, argues that we live in the era that is marked by the presence of the term landscape in all discourses and disciplines. The most hegemonic ideas and representations are those associated with nature and whose tools are often marketing strategies of ‘greenwashing’ including rooftop gardens, vertical forests, plant walls. By deepening the ideology behind that and focusing on some processes, Ferrari interrogates the cultural meaning of this phenomenon.

Addressing this grand narrative of landscape and nature in the city, with a focus on materiality and design, Tali Hatuka explores contemporary trends in landscape design. In her paper, The Generic Design of Urban Parks, she presents some of the dominant design features in the development of urban landscape. Addressing varied examples, she argues that the design of open spaces in the city is based on a pragmatic approach that further contributes to the consumption of public spaces. The paper ends with a discussion of alternative approaches and the role of complex, dynamic public spaces in our cities.

-

The Urban and Regional Perspective focuses on the way landscape projects are changing and modifying life in cities and regions. The first more conceptual paper, Branded Landscapes vs Reform of Ordinary Landscapes: An Insight from Italy, by Arturo Lanzani and Cristiana Mattioli focuses on the way landscapes have become a central component in the economic improvement and in the valorization of heritage, as well as in planning strategies. The key argument is that landscape heritage sites have become a branding tool for cultural economy. This dynamic may be seen in the context of cultural heritage policies that aim to preserve heritage from aggression and destruction, but at the same time are responsible for a new process of stereotyping and ‘showcasing’ protected heritage sites. The paper ends by proposing strategies to overcome the threats of ill-conceived and misdirected, glossy, and/or overbearing initiatives, policies and projects related to natural and designed landscape sites and projects.

Complementing these ideas, Cristina Mattiucci, in her paper, Landscape as a Founding Element of the Contemporary Urban, discusses how landscape transformations redefine the features of territories in collective imaginaries, making the landscape emerge as a strategic element in planning policies. The paper investigates an artificial basin landscape project, tracking the changes in the perception of the area by those who permanently and temporarily inhabit it. Mattiucci argues that understanding the cultural, economic, and political meanings of the landscape strongly influences territorial marketing strategies and individual living choices. In her conclusions she suggests that interpretation of the landscape in the contemporary city must go beyond addressing forms and functions, and address the cultural and political perspectives that contribute to its transformation. -

The Personal and Local level refers to initiatives and practices associated with greening cities. Addressing the phenomenon of community gardens and the discourse evolved around it, One Landscape Multiple Meanings: Revisiting Contemporary Discourses on Urban Community Gardens, by Efrat Eizenberg, maps the different ways in which scholars conceptualize the formation of, and care for, urban community gardens. It shows how these gardens are perceived both as spaces with the potential to cultivate new ideas about cooperative relations and sustainable urbanism, and as a form of a neoliberal ‘greenwashing’ development strategy. Eizenberg’s perspective takes into account the broad, and sometimes conflicting, interpretations of community gardens and offers a complex reading of what kind of landscape is produced by them.

Greening not only affects community perceptions but also the way individuals envisage their living space and conduct their day-to-day activities. Lise Bourdeau-Lepage in her paper Nature and Well-Being in the French City: Desire and Homo Qualitus, argues that individuals have become aware of the essential role played by nature, in particular in terms of their well-being. They have rediscovered the benefits of nature and seek to make the most of it. Exploring the practices of individuals in the French society, she shows how people, policy-makers and economic actors are developing an ecological conscience, and how plants and vegetation are occupying an ever more important place in cities. In her conclusion she underlines the way in which the desire for nature and the willingness to preserve the environment exposed the environment itself to a real risk of the instrumentalization of nature.

Linking both the level of the community and the individual, the last paper in the issue by Alessia de Biase, Carolina Mudan Marelli, and Ornella Zaza reminds us that we must view contemporary landscape ideas and practices in a historical perspective. In their paper, From Collective Urban Gardens to Individual Micro-Landscapes, they show that the politicization of urban nature is unavoidable. By exploring the evolution and the cultivation of landscape in the city of Paris, they explain the shift that has taken place in the public policy approach with regard to urban nature. As they argue, the individual (citizen) is becoming a dominant actor in the management of nature in the city, a role that is further enhanced by the use of digital platforms and applications that support it.

From the Fragmented to Systematic: Future Landscape Interventions in Cities

REFERENCES

- Brebbia, C.A. (2000) The Sustainable city: Urban regeneration and sustainability. Boston, MA: MIT Press.

- Burton, E., Jenks, M. and Williams, K. (2003) The Compact City: A Sustainable Urban Form? New York: Routledge.

- Brenner, N. and Schmid, C. (2015) Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City, 19, pp. 151–182.

- Duany, A. (2000) Suburban Nation: The Rise of Sprawl and the Decline of the American Dream. New York: North Point Press.

- Grove, K. (2014) Agency, affect, and the immunological politics of disaster resilience. Environment and Planning D, 32(2), pp. 240–256.

- Godschalk, D.R. (2002) Urban hazard mitigation: creating resilient cities. Natural Hazards Review, 4(3), pp. 136–143.

- Haughton, G. (1999) Environmental justice and the sustainable city. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 18(3), pp. 233–243.

- Jabareen, Y. (2013) Planning the resilient city: concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities, 31, pp. 220–229.

- Jenks, M. and Jones, C. (eds.) (2010) Dimensions of the Sustainable City. Berlin: Springer.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. (ed.) (2002) Landscape and Power, 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Mossop, E. (2006) Landscapes of infrastructure, in Charles Waldheim (ed.) The Landscape Urbanism Reader, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, pp. 163–177.

- Mostafavi, M. and Doherty, G. (eds.) (2016) Ecological Urbanism. Zurich: Lars Müller..

- Pelling, M. (2003) The Vulnerability of Cities, Natural Disasters and Social Resilience. London: Earthscan.

- Pickett, S.T.A., Cadenasso, M.L. and Grove, J.M. (2004) Resilient cities: meaning, models, and metaphor for integrating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning realms. Landscape and Urban Planning, 69(4), pp. 369–384.

- Terrin, J. (ed.) (2013) Jardins en ville. Villes en jardin. Paris: Parenthèses.

- Scheer, B. (2011) Metropolitan form and landscape urbanism, in Banerjee, T. and Loukaitou-Sideris, A. (eds.) Companion to Urban Design. London: Routledge, pp. 611–618.

- Steiner, F. (2011) Landscape ecological urbanism: origins and trajectories. Landscape and Urban Planning, 100(4), pp. 333–337.

- UN-HABITAT (2011) Urban Humanitarian Crisis: UN-HABITAT in Disaster and Conflict Contexts. Available at: http://mirror.unhabitat.org/pmss/listItemDetails.aspx?publicationID=3195.

- Vale, L.J. (2014) The politics of resilient cities: whose resilience and whose city? Building Research & Information, 42(2), pp. 191–201.

- Vale, L.J. and Campanella, T.J. (2005) The Resilient City: How Modern Cities Recover from Disaster. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Waldheim C. (ed.) (2006) The Landscape Urbanism Reader. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Wheeler, S.M. and Beatley, T. (eds.) (2008) Sustainable Urban Development Reader, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Zhang, Y. (2010) Residential housing choice in a multihazard environment: implications for natural hazards mitigation and community environmental justice. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 30(2), pp. 117–131.

Branded Landscapes in Contemporary Cities

About this issue

Summary

To what extent have we commodified landscapes and nature? How has this commodification influenced life in the city, including urban processes? Where do efforts to reclaim space within the city for nature fit in the power dynamics within cities? The papers in this issue present three perspectives on this instrumentalization of landscape and nature in cities: the paradigmatic, the urban and regional, and the local/personal.

Contents

-

The Instrumentalization of Landscape in Contemporary Cities

TALI HATUKA and CRISTINA MATTIUCCI -

Reactionary Landscape: The Discourse of Naturalism as a Grand Narrative

FEDERICO FERRARI -

Beyond Pragmatism: Challenging the Generic Design of Public Parks in the Contemporary City

TALI HATUKA -

Branded Landscapes vs Reform of Ordinary Landscapes: An Insight from Italy

ARTURO LANZANI and CRISTIANA MATTIOLI -

Landscape as a Founding Element of the Contemporary Urban

CRISTINA MATTIUCCI -

One Landscape Multiple Meanings: Revisiting Contemporary Discourses on Urban Community Gardens

EFRAT EIZENBERG -

Nature and Well-Being in the French City: Desire and Homo Qualitus

LISE BOURDEAU-LEPAGE -

From Collective Urban Gardens to Individual Micro-Landscapes

ALESSIA DE BIASE, CAROLINA MUDAN MARELLI, and ORNELLA ZAZA - Publication Reviews

Cognition and the City: An Introduction

As the title indicates, this special issue brings together two disciplinary domains: cognition as studied mainly in cognitive science, and cities as studied in disciplines such as urban studies, urban geography, architecture and the like. The first, cognitive science – The Mind’s New Science (Gardner, 1987) – is a very young discipline. It emerged in the mid 1950s out of a rebellion against the doctrine of behaviourism that dominated the behavioural sciences in the first half of the twentieth century. The second, the study of cities, is rather old with roots in antiquity in the writings of first-century BC Roman architect Vitruvius and Palladio in the renaissance. The first’s main focus of interest is the world inside the brain, while the second deals with the world outside. The first attempts to be associated with the natural sciences, while the second is part of what Herbert Simon (1969 [1996]) has termed The Sciences of the Artificial. And yet, the two are interrelated. Several cognitive science’s streams, namely, Gibson’s (1979) ecological approach, embodied cognition (Varela et al., 1994), the extended mind (Clark and Chalmers 1998) suggest that the mind extends into the external environment. In Nobel laurate E. Kandel’s (2012, p. 284) words on the visual system:

Thus, we live in two worlds at once, and our ongoing visual experience is a dialogue between the two: the outside world that enters through the fovea and is elaborated in a bottom-up manner, and the internal world of the brain’s perceptual, cognitive and emotional models that influences information from the fovea in a top-down manner.

In parallel, in the domain of cities, several streams turned their attention to the internal world. In 1960, architect Kevin Lynch published his The Image of the City with the aim of finding what it is in the external world, that is in the city, that makes it legible and imageable. About a decade later urban geographers developed the notion of mental maps (Gould and White, 1974) in an attempt to provide the positivist location theories, that then dominated human geography and urban studies, a more realistic perspective on human behaviour in the environment and specifically in cities. Their basic suggestion was that a person’s location in space has an influence on his/her spatial perception and as a consequence on location decisions. Then, students of mental maps in conjunction with those of Lynch’s Image incorporated psychologist Eduard Tolman’s (1948) seminal paper ‘Cognitive maps in rats and men’, and made the three notions – mental maps, images and cognitive maps – the foundations for behavioural geography. Since the 1990s, with the growing influence of cognitive science and in conjunction with GIS, behavioural geography gradually turned into cognitive geography (Montello, 2018; Portugali, 2018).

Lynch’s main interest in the ‘image of the city’ was the city itself – its morphology and urban landscape. However, in the context of behavioural and cognitive geography the interest shifted from the city to behaviour in space and then to spatial cognition. The city itself became just a passive environment by means of, and within which, behaviour and cognition can be studied; very much in line with the role of the external environment in cognitive science in general. In the latter, the focus of interest was and still is one-sidedly on the details of the inner world, even in the above noted ecological-embodied-extended mind approaches. ‘… to my knowledge’, writes Kelso (2016, p. 5) in a recent study of the emergence of agency in a human infant out of the interaction between the infant and a mobile in the environment, ‘not a single study has recorded the motion of the mobile, thereby obviating the possibility of obtaining any information about its relation to the baby’s movements’. Thus, despite Lynch’s image of the city and the fact that many, if not most, behavioural-cognitive geographical studies were associated with cities, the links between the ‘motion of the city’ and human cognition did not originate here; it originated in three other research fields whose main concern (similarly to Lynch’s) was the city itself: Christopher Alexander’s pattern language, Bill Hillier’s space syntax and, complexity theories of cities (CTC).

According to Alexander (1979, pp. 49–50), cities are products of a language of patterns – a ‘complex set of interacting rules … [reside] … in people’s heads and are responsible for the way the environment gets its structure’. Similar to Gestalt patterns and to Chomsky’s generative ‘internal language’, Alexander’s pattern language is innate to the human mind and thus prior to and beyond culturally related specific urban morphologies. However, it differs from Chomsky’s in that Alexander’s patterns are like ‘the semantic structure … which connects words together – such as “fire” being connected to “burn”, “red” to “passion”’ (Alexander interviewed by Grabow, 1983, p. 50).

Hillier’s focus is on ‘syntax’ – in the case of cities, the syntax of the urban space (Hillier, 2012, 1996; Hillier and Hanson, 1984). The pattern of street networks in cities, suggested Hillier, functions in a way similar to syntax in language. Similar to language in which the relationship between words in their ordering determines the meaning of a sentence, so in a city the relationship between streets in ordering determines the meaning of the urban landscape and as a consequence the behaviour of people in it.

Unlike Hillier’s and Alexander’s approaches to cities, which from the start were associated with cognition, CTC – Complexity Theories of Cities, started with no such association. This domain of studies emerged in the last three decades as an approach that applies the various theories of complexity to the study of cities, their planning and design (Batty, 2013; Portugali, 2011; Portugali et al., 2012; Portugali and Stolk, 2016). Studies in this domain demonstrate that like natural complex systems, cities too are complex self-organized and organizing systems that emerge bottom-up and exhibit phenomena of chaos, fractal structure and the like. The link between CTC and cognition follows, firstly, the fact that the mind/brain is regarded as the ultimate complex system. Secondly that, as elaborated by Portugali (2011), a deeper understanding of human behaviour in cities requires making links to cognitive science.

From the discussion above it follows that linking Cognition and the City – the aim of the present special theme issue – requires an integration between the research domains just surveyed. And indeed, the first paper by Portugali and Haken suggests such an integration. The other papers in this special issue shed light on several aspects of such an integration. Thus, the second paper by Penn, puts Cognition and the City in the wider time context of human evolution. Paper three by Blumenfeld-Lieberthal et al. explores the morphological properties that typify a city. The paper by Ishikawa that follows, the fourth in the list, explores Cognition and the City in terms of people–environment interrelations. The next paper by Omer exposes the links between ‘systematic distortions in cognitive maps’ and the morphological properties of their superordinate geographical context. The sixth paper by Bae and Montello is a case study illustrating the nature of a city’s perceptual boundaries, while the seventh paper, by Kondyli and Bhatt, discusses navigation in large-scale urban structures that are becoming more and more dominant in cities.

There is no need to say more here about the various papers and their points of view; the papers do this themselves in the most appropriate ways: they speak for themselves while their abstracts describe the essence of each paper. Instead I’ll close with reference to Kandel’s statement at the beginning of this introduction. Namely, that ‘we live in two worlds at once’, that our experience ‘is a dialogue between the two: the outside world … and the internal world…’. This dialogue, as is well recorded, has shaped humans’ cognitive evolution for thousands of years. For most of this time, the outside world was in fact, Nature and the elements of which it is composed: animals trees, stars and all the rest. This is not the case anymore: in a world where more than half of the population live in cities, for most newborns the first things that they see when they open their eyes are not trees, birds or stars, but rather buildings, cars, machines and other artificial elements that make a City. And yet, in the domain of cognition, the City of the ‘Cognition and the City’ dyad has so far been discussed mainly implicitly and as a kind of by-product: as means to expose the ‘really interesting’ internal world of entities such as cognitive maps, images, spatial perception and the like. In parallel, in the study of cities, where the main focus was traditionally on economics, society, culture and politics, the Cognition of the dyad entered the discussion for the most part as means to improve our understanding of urban agents’ decision-making. It seems that it is time for the Cognition and the City dyad to become an explicit domain of study for its own sake. This special issue is a modest step towards this aim.

References

- Alexander, C. (1979) The Timeless Way of Building. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Batty, M. (2013) The New Science of Cities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Clark, A. and Chalmers, D. (1998) The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), pp. 7–19.

- Gardner, H. (1987) The Mind’s New Science. New York: Basic Books.

- Gibson, J.J. (1979) The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Boston, MA: Houghton-Mifflin.

- Gould P. and White R.R. (1974) Mental maps. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Grabow, S. (1983) Christopher Alexander: The Search for a New Paradigm in Architecture. London: Oriel Press.

- Hillier, B. (2012) The genetic code for cities: is it simpler than we think? in Portugali, J., Meyer, H., Stolk, E. and Tan, E. (eds.) Complexity Theories of Cities have Come of Age. Berlin: Springer.

- Hillier, B. (1996) Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hillier, B. and Hanson, J. (1984) The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kandel, E. (2012). The Age of Insight: The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present. New York: Random House.

- Kelso, J.A.S. (2016) On the self-organizing origins of agency. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(7), pp. 490–499.

- Lynch, K. (1960) The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Montello, D. Ed. (2018) Handbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Portugali, J. (2011) Complexity, Cognition and the City. Berlin: Springer.

- Portugali, J. (2018) History and theoretical perspectives of behavioral and cognitive geography, in Montello, D. (ed.) Handbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 16–38.

- Portugali, J., Meyer H., Stolk, E. and Tan, E. (eds.) (2012) Complexity Theories of Cities have Come of Age. Berlin: Springer.

- Portugali, J. and Stolk, E. (eds.) (2016) Complexity, Cognition, Urban Planning and Design. Berlin: Springer.

- Simon, H.A. (1969 [1996]) The Sciences of the Artificial. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Tolman, E.C. (1948) Cognitive maps in rats and men. Psychological Review, 55, pp. 189–208.

- Varela, F.J., Thompson, E. and Rosch, E. (1994) The Embodied Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

'Cognition and the City: An Introduction'

The contributors to this issue explore the integration of two disciplinary domains – cognition as studied mainly in cognitive science, and cities as studied in disciplines such as urban studies, urban geography and architecture.

About this issue

Summary

The contributors to this issue explore the integration of two disciplinary domains – cognition as studied mainly in cognitive science, and cities as studied in disciplines such as urban studies, urban geography and architecture.

Contents

-

Cognition and the City: An Introduction

JUVAL PORTUGALI -

Movement, Cognition and the City

JUVAL PORTUGALI and HERMANN HAKEN -

The City is the Map: Exosomatic Memory, Shared Cognition and a Possible Mechanism to Account for Social Evolution

ALAN PENN -

What Makes Us Think It’s a City?

EFRAT BLUMENFELD-LIEBERTHAL, NIMROD SEROK, and ELYA L. MILNER -

People in the Environment and Environments Perceived by People: Cognitive-Behavioural Approaches to Spatial Cognition

TORU ISHIKAWA -

How are Geographical Judgments and a Geographical Entity’s Shape Connected in Cognitive Mapping

ITZHAK OMER -

Representations of an Urban Ethnic Neighbourhood: Residents’ Cognitive Boundaries of Koreatown, Los Angeles

CRYSTAL JI-HYE BAE and DANIEL R. MONTELLO -

Rotational Locomotion in Large-Scale Environments: A Survey and Implications for Evidence-Based Design Practice

VASILIKI KONDYLI and MEHUL BHATT - Publication Reviews

Forthcoming issues include: Branded Landscapes in Contemporary Cities; Sharing Space: Sharing Practices and Shared Spaces in the City; Changing Patterns of Commuting to and in the City

The Contributors

Crystal Bae is a PhD student in the Department of Geography, University of California, Santa Barbara. Her master’s research explored urban residents’ understanding of the cognitive boundaries of their neighbourhood, focusing on the physical and social features of the environment. Her PhD focuses on aspects of social interaction within paired route planning and navigation. Her research interests are in the areas of spatial cognition, navigation, and wayfinding, especially in relation to the urban built environment.

Mehul Bhatt is Professor in the School of Science and Technology at Örebro University, Sweden and Professor in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Bremen, Germany, where he leads the Human-Centred Cognitive Assistance Lab. He is director of the research and consulting group DesignSpace, and he has recently launched CoDesign Lab EU, an initiative aimed at addressing the confluence of Cognition, AI, Interaction and Design. His research encompasses artificial intelligence, spatial cognition and computation, visual perception, and human-computer interaction.

Efrat Blumenfeld-Lieberthal is a Senior Lecturer in the David Azrieli School of Architecture, Tel Aviv University and a member of the founding team of City Center, the Tel Aviv University Research Center for Cities and Urbanism. Her research interests are applying theories of complexity to urban environments; urban morphology; size distribution of entities in complex systems; and complex networks in urban and human systems. Recently, she has been focusing on smart cities and the way they influence urban development.

Hermann Haken was Professor of Theoretical Physics at Stuttgart University from 1960 to 1997. He has been visiting scientist/professor in China, England, France, japan, USA. He is one of the fathers of laser theory, and initiated synergetics that deals with the self-organization of structures and functions in complex systems. He developed mathematical tools and general concepts, that have found applications in fields ranging from physics and chemistry to biology and neuroscience, cognitive science and information. He was founder and editor of the Springer Series in Synergetics.

Toru Ishikawa is a Professor at the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies at the University of Tokyo. He specializes in cognitive-behavioural geography and geographic information science. His research interests include human spatial cognition and behaviour, wayfinding and navigation, and spatial thinking in geoscience.

Vasiliki Koydyli is a PhD candidate in the School of Science and Technology at Örebro University, Sweden. She is an architect by training and since 2016 has been a member of the DesignSpace (www.design-space.org) first as guest researcher, then as research assistant. Her research interests include spatial cognition, environmental psychology, design computing and cognition, and evidence-based design.

Elya L. Milner graduated from the Tel Aviv University School of Architecture, Magna Cum Laude. After several years working as an architect in private firms, she began a combined MA and PhD track at the Department of Politics and Government at Ben Gurion University, under the supervision of Professor Haim Yacobi. Her PhD research focuses on the construction of rights, belonging and entitlement in and to the Israeli-Palestinian contested space.

Daniel R. Montello is Professor of Geography and Affiliated Professor of Psychological & Brain Sciences at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His research is in the areas of spatial, environmental, and geographic perception, cognition, affect, and behaviour. Dan has authored or co-authored some100 articles and chapters, and co-authored or edited six books. He currently co-edits the academic journal Spatial Cognition and Computation.

Itzhak Omer is Professor of Urban and Social Geography in the Department of Geography and the Human Environment and Head of the Urban Space Analysis Laboratory at Tel Aviv University. His areas of academic interest include urban modelling, agent-based models, urban morphology, movement, spatial behaviour and cognition, urban systems and social geography of the city. His research examines processes connecting urban built environments to spatial behaviour and cognition, movement, and the formation of social and functional urban areas. He also develops agent-based models for simulating and modelling motorized and non-motorized movements in planned or in existing urban environments.

Alan Penn is Professor of Architectural and Urban Computing, and Dean of The Bartlett Faculty of the Built Environment at University College London. His research is into the effect of the spatial design of the built environment on the social and economic function of organisations and communities.

Juval Portugali is Professor of Human Geography in the Department of Geography and the Human Environment, Tel Aviv University. Head of City Center, Tel Aviv University Center for Cities and Urbanism, and of the Environmental Simulation Laboratory (ESLab). His research integrates complexity and self-organization theories, environmental-spatial cognition, urban dynamics and planning in modern and ancient periods. His publications include more than 70 research articles and 16 books.

Nimrod Serok is a PhD candidate at the Azrieli School of Architecture at Tel Aviv University, where he also completed his BArch and MArch (both first in his class). His work focuses on urban complexity with an emphasis on urban mobility patterns and spatio-temporal data analysis. He is experienced as a practicing architect and urban planner.

Editorial: Inclusive Design: Towards Social Equity in the Built Environment

As this special issue of Built Environment on Inclusive Design was coming to fruition, an article in The Guardian posed the question ‘what would a truly disabled-accessible city look like?’ (Salman, 2018). The piece identified that globally by 2050, 940 million people with disabilities will live in cities (this equates to 15 per cent of all urban dwellers) resulting in the United Nations declaring that the inaccessibility of our built environment is a ‘major challenge’. Salman’s article also presented an economic value to poor access – in the UK this is estimated to be £212bn (known as the purple pound), with an accessible tourism market estimated at £12bn. The article then presented a series of cases from around the world to highlight how greater access to the built environment was being achieved through design. This included the ‘traditional’ focus of inclusive design in considering the needs of our ageing and disabled populations (with an emphasis on mobility and sight), as well as considerations for citizens (or city/sens – citizens of urban environments who experience sensory barriers) on the autistic spectrum.

While these innovations should be welcomed and celebrated, they also require a degree of careful consideration. The critical access theorist Aimi Hamraie has challenged many inclusive, universal and ‘design for all’ responses that have sought to include ‘everyone’ by asking ‘who counts as everyone and how designers can know?’ (Hamraie, 2017, p. 261). Given this perspective how might inclusive design further social equity in the built environment? All too often an inclusive approach can consider the needs of one group of users to the detriment of another. This has been most commonly adopted in the design of streets and public spaces in the generic use of textured, tactile or ‘blister’ paving as navigational direction for blind and vision impaired people. Yet for older people, people who use wheelchairs or scooters (Omerod et al 2014) or have artificial lower limbs (Bichard, 2015) this design intervention has created further barriers to accessing curb cuts (in itself a defining symbol of access to the built environment (Haimraie, 2017)). Often many of the interventions in the built environment that are considered ‘inclusive’ such as tactile paving, ramps, hearing loops, and even the accessible toilet should be considered more in line with design for ‘special needs’ (Hanson, 2002). Hence the inclusive design project for the built environment continues to be an urgent and ongoing priority that offers opportunities for innovation and collaboration but, more importantly, extends access beyond being merely a function of the built environment. Rather it is a crucial element that incorporates human diversity and potential within our natural environment.

Inclusive design within the UK initially focused on the needs of the ageing population (Coleman, 1994); this was then extended to include disabled people (Keates et al., 2000). More recently, wider social factors including economic exclusion have also come into the inclusive design framework, and this has included extending user participation from ‘extreme users’ (Coleman, 1994), user groups (Dong et al., 2005) to wider cross community participation (Bichard et al., 2018) to incorporate and develop design knowledge of functional access in more creative and innovative forms.

The contributors to this issue of Built Environment represent a series of researchers who are extending inclusive design knowledge, in teaching, practice and thinking. What this issue does not include is consideration of user engagement. Inclusive design has tended to assume that mere consultation will result in favourable design outcomes, but often this consultation itself requires careful consideration and creative engagement for both the users and the designers. Methods for engagement have become the focus of their own specific design discourses including participatory and co-design, and are context led. While offering a wide spectrum of creative engagement for users and designers, such narratives are worthy of their own publications and special editions, and therefore have not been included in this special edition.

Instead the papers presented here represent a series of wider considerations for readers of Built Environment (the users). The first paper by Scott, McLachlan and Brookfield lay the foundation of this issue where many built environment professional careers begin; training in architectural schools. Scott et al. describe three innovative projects from the architectural school that not only engage key levels of the education but also actively extend inclusive design engagement from the older user to the citizen. The first two cases identify how communication between designer and user are essential, requiring the designer to step back from the education bubble of design school rhetoric. Their third example illustrates how the regulation and design code that informs design for access, such as Building Regulations and British Standards, can be seen as tools for innovation – therefore meeting the legislative requirements and extending the design guidance whilst offering creative engagement for designers and innovative potential outcomes for users.

The second paper of this issue introduces the inclusive design paradox. Heylighen and Bianchin show how the uptake of inclusive design has been limited, and whilst some of this might be considered a lack of engagement of inclusive design within the education of built environment professionals (Scott et al.), there is also the consideration of wider conflicting issues and the influence of design on users. Heylighen and Bianchin present this as the paradox which focuses on a question of justice and which the authors navigate through the work of moral and political philosopher John Rawls to explore questions of justice in design and how the architects of the built environment might extend design for fairness. The authors present a series of specific design outcomes they consider as having challenged this paradox of inclusive design.

The third paper introduces ‘auraldiversity’ as a specific oversight within inclusive design of the built environment. Renel shows how design has focused on an auraltypical perspective. This can be extended within inclusive design to suggest that an element of ‘typical’ user-centred design has focused on specific disabilities. By introducing auraldiversity, Renel reveals the complexity and richness of hearing, and highlights that maybe this has been difficult to focus on within inclusive design research and that such diversity cannot be met by a single-issue response such as the hearing induction loop. Again, the focus on a specific aspect of human physical diversity can be extended to consider shared commonalities across spectrums and incorporated into a wider inclusive design investigation between disciplines. By introducing the reader to three aurally diverse participants, Renel highlights how negative and positive aspects of the built environment can impact their lives.

From a focus in a specific diversity, a specific element of the built environment is investigated in the fourth article in this issue. Ramster, Greed and Bichard present the challenge of toilet provision as essential for mobility in the built environment, but facing current challenges with regards to perceived legitimate access to provision. This case illustrates how, without wider consultation, design considerations regarded inclusive can become exclusive. This was manifested most recently in the emergence of gender neutral toilet provision: signage change rather than wider design consideration and possible innovation resulted in news headlines and controversy at the most basic of design intervention requirements of the built environment.

In their book Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability, Aimi Hamraie challenged the origins of universal and inclusive design as the result of specific progressive legislation (such as the American with Disabilities Act) to reveal the politics and discourses that contribute to knowledge making of design and the specific bodies design responded to. The work has been described by leading inclusive design in the built environment theorist Rob Imrie as a major text that will reconstruct how ‘we think about access, disability and design’. In their essay for this issue Hamraie presents new research that extends the lens of inclusive considerations to explore wider discussions of health and wellness/wellbeing that pervade many city design projects, highlighting that certain design rhetorics that masquerade as sustainable (and by association inclusive) are essentially designing the exclusion of certain socio/economic populations. This is especially explored in the notion of making areas of cities ‘liveable’ that suggests these current spaces are unliveable, despite people living there. In line with the critical access approach outlined in their book, Hamraie shows, maybe somewhat uncomfortably for inclusive design practitioners, how the focus of this design approach has predominantly centred on making bodies more productive with no critical consideration of the wider neoliberal ideology that drives city redesign. Hamraie’s critical access studies can be considered an active companion to inclusive design.

The final paper in this issue focuses on one of the most horrific incidents of built environment design to have occurred in the UK. The fire at Grenfell Tower in 2017 resulted in the loss of seventy-one lives. Evans continues his previous work on the challenges of designing sustainably and inclusively to show how these design approaches continue to be mutually exclusive, in which due to government targets, sustainability and a buildings performance is often a higher priority than the requirements of the users of the building. Evans also shows that an inclusive approach – especially in the design of housing, does not necessarily mean the creation of new knowledge, but that a previous legacy of innovative inclusive design can be re-examined.

The papers in this issue aim to present wider considerations of inclusive design, for the practitioners, educators and theorists behind this specific people-centred engagement. They are not intended to be solutions to the problem, rather they reveal the complexity of inclusion that requires greater research and engagement with populations in recognition of the diversity of those who inhabit the built environment.

References

- Bichard, J. (2015) Extending Architectural Affordance; The Case of the Publicly Accessible Toilet. PhD Thesis, University College London. Available at: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1467131/2/Bichard%202014%20Res.pdf.

- Bichard, J., Alwani, R., Raby, E., West, J. and Spencer, J. (2018) Creating an inclusive architectural intervention as a research space to explore community wellbeing, in Langdon, P., Lazar, J., Heylighen, A. and Dong, H. (eds.) Breaking Down Barriers. New York: Springer.

- Dong, H., Clarkson, P.J., Cassim, J. and Keates, S. (2005) Critical user forums – an effective user research method for inclusive design. The Design Journal, 8(2), pp. 49–59.

- Coleman R. (1994) The case for inclusive design – an overview, in Proceedings of the 12th Triennial Congress of the International Ergonomics Association. Mississauga, Ontario: Human Factors Association of Canada.

- Hamraie, A. (2017) Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Hanson, J. (2002) The inclusive city: what active ageing might mean for urban design, in Maltby, T. (ed.) Active Ageing: Myth or Reality? Proceedings of the British Society of Gerontology 31st Annual Conference. Birmingham: University of Birmingham.

- Keates, S., Clarkson, P. J., Harrison, L.A. and Robinson, P. (2000) Towards a practical inclusive design approach, in Thomas, J. (ed.) Proceeding of CUU’00: ACM Conference on Universal Usability. New York: ACM, pp. 45–52.

- Omerod, M., Newton, R., MacLennan, H., Faruk, M., Thies, S., Kennedy, L., Howard, D. and Nester, C. (2014) Older people’s experiences of using tactile paving. Municipal Engineer, 168(1), pp. 3–10.

- Salman, S. (2018) What would a truly disabled-accessible city look like? The Guardian, 14 February. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2018/feb/14/what-disability-accessibl....

Meet the editor

Jo-Anne Bichard is Senior Research Fellow at the Royal College of Art Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design. She is a design anthropologist whose research involves multi/inter-disciplinary collaboration and participatory engagement in the inclusive design process. Her primary research theme focuses on design for wellbeing in the built environment. With Gail Ramster, Jo-Anne is co-creator of The Great British Public Toilet Map and was runner up in the ESRC’s Outstanding Impact in Society award. Jo-Anne’s PhD ‘Extending Architectural Affordance; the case of the Publicly Accessible Toilet’ explored inclusive spatial, product and service design as crucial elements to afford access for users across abilities and age. She has published extensively on toilet design from an inclusive perspective.

Inclusive Design: Towards Social Equity in the Built Environment

The papers in this issue aim to present wider considerations of inclusive design, for the practitioners, educators and theorists behind this specific people-centred engagement. They are not intended to be solutions to the problem, rather they reveal the complexity of inclusion that requires greater research and engagement with populations in recognition of the diversity of those who inhabit the built environment.

About this issue

Summary

The papers in this issue aim to present wider considerations of inclusive design, for the practitioners, educators and theorists behind this specific people-centred engagement.

Contents

-

Inclusive Design: Towards Social Equity in the Built Environment

JO-ANNE BICHARD -

Inclusive Design and Pedagogy: An Outline of Three Innovations

IAIN SCOTT, FIONA MCLACHLAN and KATHERINE BROOKFIELD -

Building Justice: How to Overcome the Inclusive Design Paradox?

ANN HEYLIGHEN and MATTEO BIANCHIN -

‘Auraldiversity’: Defining a Hearing-Centred Perspective to Socially Equitable Design of the Built Environment

WILLIAM RENEL -

How Inclusion can Exclude: The Case of Public Toilet Provision for Women

GAIL RAMSTER, CLARA GREED and JO-ANNE BICHARD -

Enlivened City: Inclusive Design, Biopolitics, and the Philosophy of Liveability

AIMI HAMRAIE -

Inclusive and Sustainable Design in the Built Environment: Regulation or Human-Centred?

GRAEME EVANS - Publication Reviews

High-Rise Urbanism in Contemporary Europe

About this issue

Summary

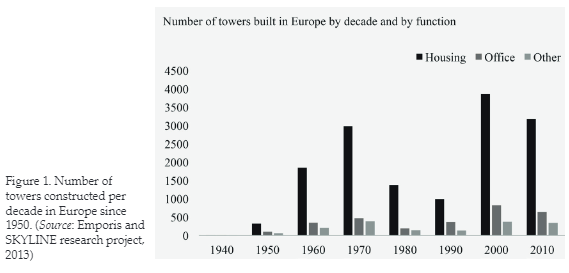

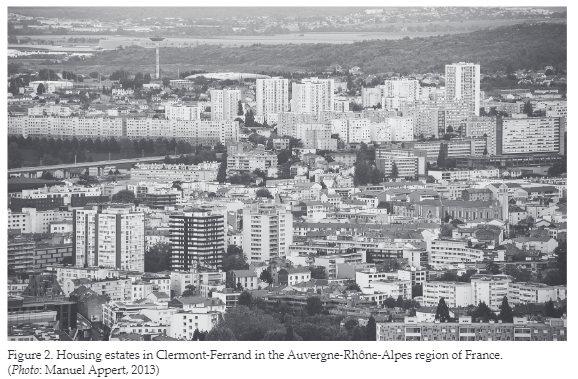

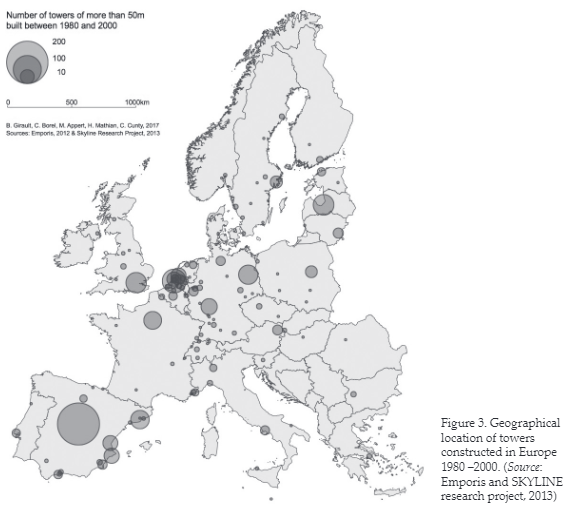

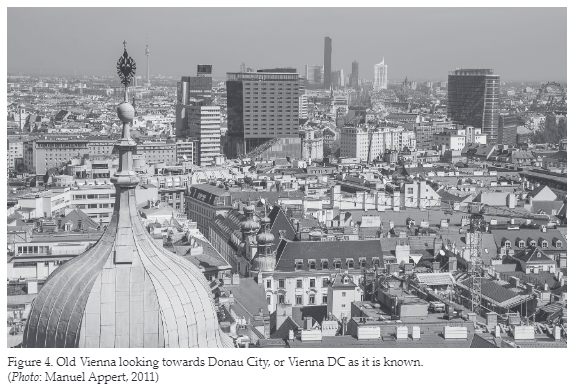

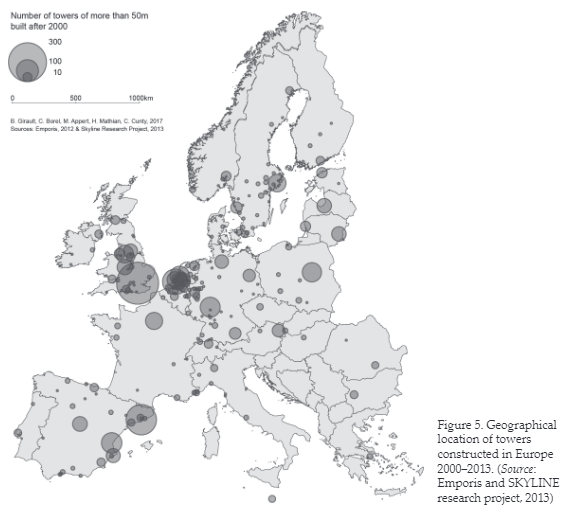

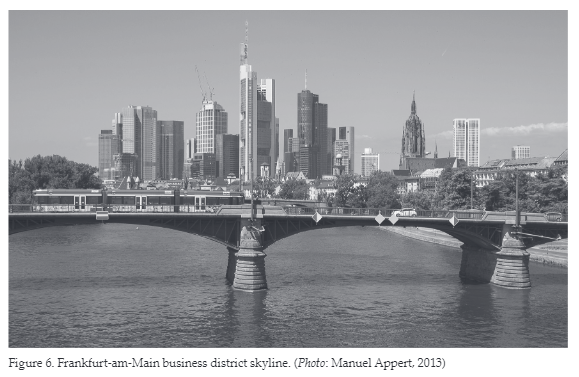

This issue of Built Environment explores the processes of contemporary European urban verticalization and examines what these recent upward trajectories indicate about the social, political, economic and cultural dynamics of European urbanization.

- Al-Kodmany, K. (2017) Understanding Tall Buildings: A Theory of Placemaking. New York: Routledge.

- Appert, M. (2012) skyline policy: the shard and London’s high-rise debate. Metropoli-tics. available at: http://www.metropoli-tiques.eu/skyline-policy-the-shard-and.html.

- Appert, M. (2016) The resurgence of towers in European cities. Metropolitics. available at: http://www.metropolitiques.eu/The-Re-surgence-of-Towers-in.html.

- Appert, M., Huré, M. and Languillon, R. (2017) Gouverner la ville d’exception et ville ordinaire. Géocar-refour, 91(2), pp. 3–12.

- Appleyard, D. (1979) The Conservation of Euro-pean Cities. Cambridge, Ma: MIT press.

- Backouche, I. (2016) Paris transformé: le Marais, 1900–1980: de l’îlot insalubre au secteur sau-vegardé. paris: Créaphis.

- Beeckmans, L. (2014) The adventures of the French architect Michel Ecochard in post-independence Dakar: a transnation-al development expert drifting between commitment and expediency. The Journal of Architecture, 19(6), pp. 849–871.

- Charney, I. and Rosen, G. (2014) splintering skylines in a fractured city: high-rise geog-raphies in Jerusalem. Environment and Plan-ning D, 32(6), pp. 1088–1101.

- Cohen, J.-L. (1995) Scenes of the World to Come: European Architecture and the American Chal-lenge, 1893–1960. parisand Montréal: Flam-marion; Canadian Centre for architecture.

- Delafons, J. (1998) Politics and Preservation: A Policy History of the Built Heritage, 1882–1996. London: E & FN spon.

- Drozdz, M. and appert, M. (2012) Re-Un-derstanding the CBD: a Landscape per-spective. LaTTsworking paper. available at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00710644.

- Esher, L. (1981) A Broken Wave: The Re-building of England, 1940–1980. London: allen Lane.

- Fredenucci, J.-C. (2003) L’entregent colonial des ingénieurs des ponts et Chaussées dans l’urbanisme des années 1950–1970. Vingtième Siècle. Revue d’histoire, 79(3), pp. 79–91.

- Gartman, D. (2000) why modern architecture emerged in Europe, not america: the new class and the aesthetics of technocracy. The-ory, Culture & Society, 17(5), pp. 75–96.

- Glauser, a. (2016) Contested cityscapes: pol-itics of vertical construction in paris and Vienna, in Lopez, J.T. and Hutchison, R. (eds.) Public Spaces: Times of Crisis anville verticale: entre ange. Bingley: Emerald Group publish-ing, pp. 221–254.

- Graham, s. and Marvin, s. (2001) Splintering Urbanism: Networked Infrastructures, Tech-nological Mobilites and the Urban Condition. London: Routledge.

- Graham, S. and Hewitt, L. (2013) Getting off the ground on the politics of urban verti-cality. Progress in Human Geography, 37(1), pp. 72–92.

- Grubbauer, M. (2014) Economic imaginaries and urban politics: the office tower as so-cially classifying device. International Jour-nal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(1), pp. 336–59.

- Harris, a. (2015) Vertical urbanisms opening up geographies of the three-dimensional city. progress in Human Geography,39(5), pp. 601–620.

- Hatherley, O. (2016) Landscapes of Communism: A History Through Buildings. London: pen-guin Books.

- Jacobs, J.M., Cairns, s. and strebel, I. (2012) Materialising vision: performing a high-rise view, in Rose, G. and Tolia-Kelly, D.p. (eds.) Visuality/Materiality: Images, Objects and Practices. London: Routledge, pp. 133–152.

- Kaddour, R. (2016) The complex repre-sentations of working-class residential towers. The rise and fall of the plein Ciel tower in three acts. Metropolitics. avail-able at: http://www.metropolitiques.eu/The-complex-representations-of.htm-l?lang=fr.

- Kaika, M. (2010) architecture and crisis: re-in-venting the icon, re-imag(in)ing London and rebranding the City. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35(4), pp. 453–474.

- Kasmi, a. (2017) The plan as a colonization project: the medina of Tlemcen under French rule, 1842–1920. Planning Perspec-tives. https://doi.org/10.1080/02665433.2017.1361335.

- Lizieri C. (2009) Towers of Capital: Offices Markets and International Financial Services. Chichester: wiley-Blackwell.

- Monclus, J. and Dies Medina, C. (2016) Mod-ernist housing estates in European cities of the western and Eastern blocs. Planning Perspectives, 31(4), pp. 533–562.

- Picard, a. (1994) architecture et urbanisme en algérie. D’une rive à l’autre (1830–1962). Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditer-ranée, 73(1), pp. 121–36.

- Power, a. (1993) Hovels to High Rise: State Housing in Europe Since 1850. London: Routledge.

- Sailer-Fliege, U. (1999) Characteristics of post-socialist urban transformation in East Central Europe. GeoJournal,49(1), pp. 7–16.

- Stanek, Ł. (2012) Introduction: the ‘Second world’s’ architecture and planning in the ‘Third world’. The Journal of Architecture, 17, pp. 299–307.

- Swenarton, M., avermaete, T. and Van den Heuvel, D. (2014) Architecture and the Wel-fare State. London: Routledge.

- Taillandier, I., Namias, O. and pousse, J.-F. (ed.) (2009) L’invention de la tour européenne. The invention of the European tower. paris: pavillon de l’arsenal; picard.

- Turkington, R., Van Kempen, R. andwassenberg,F. (2004) High-Rise Housing in Europe: Cur-rent Trends and Future Prospects. Delft: Delft University press.

- Verdeil, E. (2012) Michel Ecochard in Lebanon and syria (1956–1968). The spread of mod-ernism, the building of the independent states and the rise of local professionals of planning. Planning Perspectives, 27(2), pp. 249–66.

- Weber, R. (2015) From Boom to Bubble: How Finance Built the New Chicago. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago press.

Meet the editors

About this issue

Summary

This issue of Built Environment explores the processes of contemporary European urban verticalization and examines what these recent upward trajectories indicate about the social, political, economic and cultural dynamics of European urbanization.

Manuel Appert is a Senior Lecturer in Geography and Planning at Université Lyon 2 and a member of the mixed research unit UMR 5600 – Environnement Ville Société. His research concerns the instrumentalization of architecture in urban governance. He has recently worked on the regulation of tall buildings in London and led a research team on skyline issues in European cities. His more latest work deals with planning regulations and the vertical city.

Manuel Appert is a Senior Lecturer in Geography and Planning at Université Lyon 2 and a member of the mixed research unit UMR 5600 – Environnement Ville Société. His research concerns the instrumentalization of architecture in urban governance. He has recently worked on the regulation of tall buildings in London and led a research team on skyline issues in European cities. His more latest work deals with planning regulations and the vertical city.

Martine Drozdz is a member of the French Council for Scientific Research (CNRS). She is a Research Fellow at Laboratoire Techniques Territoires et Sociétés and teaches at Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées and at the Paris School of Urban Planning. Her research explores the contemporary dynamics of urban democracy in relation to urban planning through a socio-technical lens, with a focus on London and Paris.

Martine Drozdz is a member of the French Council for Scientific Research (CNRS). She is a Research Fellow at Laboratoire Techniques Territoires et Sociétés and teaches at Ecole Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées and at the Paris School of Urban Planning. Her research explores the contemporary dynamics of urban democracy in relation to urban planning through a socio-technical lens, with a focus on London and Paris.

Andrew Harris is a Senior Lecturer in Geography and Urban Studies at University College London, where he convenes the interdisciplinary Urban Studies MSc and is a Co-Director of the UCL Urban Laboratory. His research develops critical perspectives on the role of art, creativity and culture in recent processes of urban restructuring, and on three-dimensional geographies of contemporary cities, especially London and Mumbai.

Andrew Harris is a Senior Lecturer in Geography and Urban Studies at University College London, where he convenes the interdisciplinary Urban Studies MSc and is a Co-Director of the UCL Urban Laboratory. His research develops critical perspectives on the role of art, creativity and culture in recent processes of urban restructuring, and on three-dimensional geographies of contemporary cities, especially London and Mumbai.

High-Rise Urbanism in Contemporary Europe

This issue of Built Environment explores the processes of contemporary European urban verticalization and examines what these recent upward trajectories indicate about the social, political, economic and cultural dynamics of European urbanization. Through a combination of particular case-studies from across Europe, the issue investigates the relationship in European cities between high-rise built fabric and planning regimes, financial flows, cultural representations, technical innovations, and forms of modernist heritage.

About this issue

Summary

This issue of Built Environment explores the processes of contemporary European urban verticalization and examines what these recent upward trajectories indicate about the social, political, economic and cultural dynamics of European urbanization.

Contents

-

High-Rise Urbanism in Contemporary Europe

MARTINE DROZDZ, MANUEL APPERT and ANDREW HARRIS -

1980s London: A Laboratory for Contemporary High-Rise Architecture. The Case of the Richard Rogers Partnership

LOÏSE LENNE -

Skyscraper Development and the Dynamics of Crisis: The New London Skyline and Spatial Recapitalization

DAVID CRAGGS -

The Governance of Office Tower Projects in a European Second City: The Case of Lyon

MAXIME HURÉ, CHRISTIAN MONTÈS and MANUEL APPERT -

Reaching New Heights: Post-Politicizing High-Rise Planning in Jerusalem

GILLAD ROSEN and IGAL CHARNEY -

Questioning the Vertical Urbanization of Post-Industrial Cities: The Cases of Turin and Lyon

ELENA GRECO -

Exploring the Skyline Rotterdam and The Hague: Visibility Analysis and Its Implications for Tall Building Policy

STEFFEN NIJHUIS and FRANK VAN DER HOEVEN -

In the Shadow of the High-Rise: The Lähiö in Contemporary Finnish Cinema

ESSI VIITANEN -

Deconstructing the ‘Formula One of Housing’: Screen Representations of Malmö’s Turning Torso

PEI-SZE CHOW -

Renewal and ‘Deverticalization’ in French Social Housing: The Emblematic Case of the Rhône-Alpes Region

VINCENT VESCHAMBRE -

The Repoliticization of High-Rise Social Housing in the UK and the Classed Politics of Demolition

VIKKI MCCALL and GERRY MOONEY - Publication Reviews